It is that time of year again – the 95th Academy Awards are tonight, bringing somewhat of an official end to the cinematic year. As is tradition, I spend today reflecting on the past year, looking at the films that made the most profound difference, and those which represent the best that cinema had to offer. Unlike the Academy Awards, which is focused on compartmentalizing a few films into different categories and voting for the one that reigns supreme, I prefer to take a more in-depth and holistic look at the cinematic output from the past year, focusing less on the individual components, and more on the overall experience. As usual, making this list was a challenge, since every year we find new and exciting works that could feasibly belong on a list like this – but unfortunately, listing every title that made an impact in some way would be far too long, and some of the real gems would be lost in the process. This list represents onto a small sample of what 2022 had to offer in terms of film – and even that classification is being questioned, with many productions for television being profoundly cinematic, questioning the boundaries between the two. While I am not as intrepid as Cahiers du Cinéma in terms of placing a television show on the list, I just want to acknowledge some of the immensely powerful work done in the smaller medium, with shows like The White Lotus: Sicily, The Sandman and Cunk on Earth all being highlights in particular. We are seeing continued overlap in all areas, and ignoring the impeccable work being done in another medium seems foolish when looking at the triumphs of the past year.

Through the process of reviewing the past twelve months in cinema, 2022 is almost exactly like any other year, in terms of challenges and triumphs, tragedies and celebrations, and nearly everything in between. We’ve seen many great artists on both sides of the continue doing terrific work, as well as a few coming back from slight or total absences from the medium. Whether veterans like Steven Spielberg or Park Chan-wook continue to prove that they are masters of the craft, or unexpected returns from the likes of Todd Field and Jerzy Skolimowski who not only make their first films in years, but arguably some of their best work. It signalled the return to the screen for Brendan Fraser in the comeback story of the year, and as an introduction to many exciting new talents, with debuts from both actors and directors that represent the future of cinema in a way that is always exciting, proving that this is a medium that is far from dying. We sadly lost several great actors in this time, far too many to list here (especially since including some means we will elide others, which is not fair), and their legacy has continued to set a foundation for the medium as a whole. In short, 2022 was a challenging and exciting year, and while it always remains to be seen how it will be viewed in hindsight in terms of cinematic output, it is obvious that it is one that is filled with landmark films, especially those that feature subjects orbiting around representation – whether in terms of race, sexuality or gender, cinema has continued to be inclusive, making efforts to amplify and celebrate distinct voices, which is exciting and enthralling, and proves that our industry is moving forward in unexpected but brilliant ways.

So, without any further ado, here are my choices for the best films of the past year. As always, it has been divided into a set of honourable mentions, representing the films that didn’t quite represent the best the year had to offer, but still warranted a mention, even if only briefly. This is then followed by the fifteen films selected as the best of the year – each one a compelling, important work that carries a lot of significance and develops on its many complex ideas, or offers something that made the past year so extraordinarily special. As always, eligibility is difficult to gauge, considering the different release dates that cause many films to be considered in different years. I have done my best to keep it as contained to the past year as possible, but as usual there are a couple that would appear on lists from the previous year, as well as some that may be present in the forthcoming year. Regardless, each one of these films is special, and regardless of what year in which they were released, they deserve praise and attention in an abundance.

Honourable Mentions

The Best Films of 2022

There are some authors whose works are appropriately cited as being “unadaptable”, and Don DeLillo has long been considered something of a Holy Grail writer in terms of his work not being particularly successful when attempts have been made to bring it to the screen. However, as we saw nearly a decade ago when Paul Thomas Anderson made the first official adaptation of a Thomas Pynchon novel (another author who was cited as having written books that are impossible to translate to the screen), all it takes is a strong director. Noah Baumbach is supremely talented, a fantastic writer and director who has been working laboriously for over a quarter of a century to carve his own niche within the world of independent cinema. White Noise is by far his most ambitious production to date, and it certainly feels like it warranted the time to be brought to the screen. A dark, disquieting postmodern odyssey centred around the decline of society, carefully put together by a director whose sardonic sense of humour interweaves with the existential despair of DeLillo’s material – it is a perfect match, and what we receive is an absurdist masterpiece, a clever and biting satire that never takes itself too seriously, despite seeing out ways to plumb the very depths of the human condition. It covers every topic, from existential philosophy to the very nature of morality and our role in the wider world – and then just as it seems like we are about to get the answers we are seeking, we find ourselves confronted with an elaborate dance number, which reminds us of the most important philosophy that only a few seem to realize as being the actual meaning of life: nothing else matters, so why not just dance like no one is watching, since there is nothing else to do when you are consumed by the all-encompassing dread that is contemporary existence.

Luca Guadagnino has worked across a few different genres, and has touched on a number of themes in each one of his projects. However, the connective thread that binds them together is his forthright fascination with the human condition. This is clear in each story he tells, but it manifests most clearly in Bones and All, which is oddly one of his most humane films, despite it being about those who exist on the margins of morality. For some, this is not going to be a comfortable film – it is already a bold premise, being a romantic drama centred on the trials and tribulations of a pair of young cannibals making their way across the United States, searching for new victims to satiate their growing carnal desires. Yet, there is so much beauty in how Guadagnino explores their world. In the end, we find that Bones and All is not actually about cannibalism at all, but rather uses this as a theme to explore the concept of outsiders, people who find themselves isolated in a world that is not fully accessible to them. The combination of bleak and often disturbing imagery with a genuinely beautiful sense of soulfulness (especially reflected in the relationship between the two main characters, strikingly portrayed by Taylor Russell and Timothée Chalamet) makes this a challenging but rewarding film, a story that is not afraid to be dark, since it knows beneath the harrowing content, there is a tenderness that could only emerge through challenging conversations.

One of the great artistic fallacies is that satire is supposed to make the audience feel comfortable – and while this is mostly very true of contemporary satires, there are some that exist to create a much more hostile, challenging atmosphere. Honk for Jesus. Save Your Soul. manages to do both, with Adamma Ebo, in her directorial debut, telling the story of a disgraced pastor and his long-suffering wife, who has stood by his side through the various trials and tribulations of their personal and professional lives, only to find her own sanity gradually eroding as she begins to question not only her faith in the marriage, but her commitment to this way of life as a whole. Anchored by an astonishing performance from the effortlessly talented and outrageously funny Regina Hall, who creates yet another memorable character, as well as Sterling K. Brown, who sets aside his more congenial persona to play a hedonistic pastor who is more dedicated to worshipping the almighty dollar than the God he supposedly preaches to. Dark, satirical and deeply scathing, this film shows a darker side of humanity, one that is far more intimidating than anything else we could possibly imagine coming from this seemingly upbeat material, and there are enough surprises embedded deep within this film to keep us engaged and interested, even if some of them may not be particularly pleasant to encounter.

Joanna Hogg’s recent resurgence in the past few years has been a wonderful surprise – by no means a greenhorn, she resided in relative obscurity, being known as a very creative but otherwise mostly ignored filmmaker trying to make her way through the British independent film industry with a few well-regarded but niche pieces. Her success has to be attributed to her immersive and brilliant work in adapting her own early adult life onto film – the diptych of The Souvenir is one of the most revealing and honest works we have ever seen on the subject of artistic creation, and has been appropriately celebrated. However, the secret third part of that project (insofar as it is a separate story, but one that has inextricable ties to the previous two films in terms of being the director’s reflections on her own life, this time the relationship she had with her mother) is possibly her finest work to date. A psychological drama that plays like a gothic horror with a few interesting uses of absurd humour, The Eternal Daughter is a revelatory experience, a dark and deceptive depiction of a relationship on its last legs, but which holds many secrets that come as a genuine surprise, including one scene in particular that is by far the most devastating moment of realization from a film from the past year. Anchored by Tilda Swinton in yet another instance of dual roles, the film is an exquisite and detailed analysis of femininity, family and identity, all filtered through the engaging story of creating art, something that Hogg has clearly mastered.

If there was ever a film that warranted the label of “the little film that could”, it would be Everything Everywhere All at Once. It is doubtful that any of us could have predicted that this quaint independent science fiction dark comedy by a pair of directors that had staked their claim by making a film in which Daniel Radcliffe played a flatulent corpse, could become the year’s most compelling and adored film. Certainly not a film that embodies the concept of perfection (although the entire concept of the film is about appreciating and celebrating the individual flaws that exist within each one of us), this film was accurately turned into a mainstream phenomenon – it was a film that presented science fiction to those who preferred more quiet independent fare, while offering insightful philosophical commentary to viewers that were more accustomed to visual-heavy blockbusters. As crude as it may be to say, there is something for everyone in this film, and while this may ultimately make it slightly more divisive within certain circles that aren’t as open-minded to more off-the-wall storytelling as others (it is hardly surprising that the majority of the adoration this film has gotten has been from the younger generation – although we shouldn’t disparage older viewers that have championed this film), it is bold and ambitious filmmaking – and coming in a year defined by cinematic maximalism, Everything Everywhere All at Once walks away as one of the most impressive achievements.

He is not a filmmaker that is immune to criticism (nor has he ever claimed to be a perfect artist), but Guillermo del Toro has always proven to embody the spirit of candour with his work, making the films he would like to watch, rather than being driven by more pretentious ambitions. His finest works have always entailed some sense of childlike wonder and curiosity, and it feels like most of these are used as the foundation for one of his passion projects, an adaptation of the classic story Pinocchio. Intending to strip the story of the overly twee, sanitized appearance it normally takes, and instead returning it to the darker, more unsettling roots of Carlo Collodi’s original text, he makes a minor miracle of a film, a beautiful, well-crafted stop-motion masterpiece that is filled to the brim with passion and fury. An animated film that is defined by both its beautiful narrative and gorgeous artistry (in an industry where it is often a matter of choosing between the two), and driven by a sense of wonder and provocation, Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio is some of his greatest work, and just a marvel all on its own, which was created in collaboration with the equally fantastic Mark Gustafson. By this point, we shouldn’t be surprised when del Toro proves himself to be capable of pure brilliance, but yet he keeps finding ways to catch us off-guard, continually proving himself to be one of our finest storytellers and visual stylists.

Food has never felt more repulsive than when filtered through the lens of Peter Strickland’s camera. One of our most brilliant contemporary filmmakers returns with another deceptive masterpiece, this time taking aim at the world of “sonic catering”, in which a group of performers use food to create the most disturbing and repellent sounds, which is done for the perverse entertainment of a group of the elite, who find pleasure in the grotesque. Much like every one of his films, Flux Gourmet sees Strickland pushing boundaries in ways that we did not even realize they could be pushed – challenging and strange, but also oddly endearing (possibly being his funniest film, which is mainly attributed to the rogues gallery of a cast he assembles, with Fatma Mohamed in particular being the highlight), and while we are not always particularly comfortable with what we are seeing on screen, we can still appreciate its artistic merits, and the fact that Strickland’s experimental approach is indicative of his immense talents, and willingness to go against the status quo in increasingly bizarre ways. It may not be as unimpeachable as his more acclaimed masterpieces, but it is still a fantastic film nonetheless, and worthy of just as much attention, especially for those of us who have a taste for the absurd, no pun intended.

There are many ways to tell a good filmmaker from a great one – and perhaps the most interesting is seeing if they can take the most absurd or banal concept, and not only make it effective, but turn it into a fascinating and beautiful film. Jerzy Skolimowski has long been considered one of the greatest directors of his generation – he is one of the last remaining bridges we have to the rebellious cinema that swept over Europe in the 1960s, and he has carried with him the experiences of being an artist during the reign of the Soviet Union, which he actively fought against in his films, whether directly or through more covert means. If anyone was going to take the concept of telling a story about a donkey making its way across Europe as it seeks salvation, and turn it into something remarkable, it would certainly be the director who has built his career off challenging conventions. Immersive in a way that very few films tend to be, and beautifully poetic in both form and execution, Eo is the kind of heartfelt ode to humanity that touches us in unexpected ways. Much like Robert Bresson, whose film Au Hasard Balthazar was the spiritual ancestor to this film, Skolimowski discusses the various facets of the human condition – comedy and tragedy, compassion and cruelty – through the perspective of an animal, who proves to be an incredible protagonist. Unexpectedly beautiful and deeply striking, Eo is the work of a true master, and a film that will certainly be remembered as one of the most profoundly complex meditations on existence for years to come.

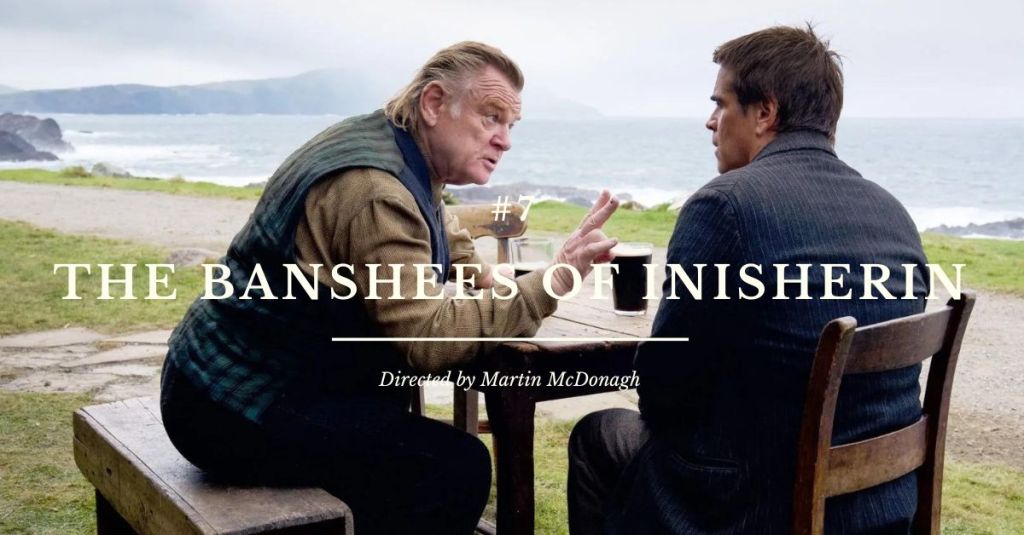

“You used to be nice” – very rarely have so few words have had as much impact as in Martin McDonagh’s masterful The Banshees of Inisherin, in which he tells the story of two lifelong friends who have spent nearly every day of their lives together on the quaint island of Inisherin, but who suddenly find their friendship coming to an abrupt halt when one of them decides that it is not worth maintaining a relationship with someone you don’t particularly like. What starts as a strange and trivial premise flourishes into a deeply complex meditation on the human condition, touching on themes surrounding identity, family and existence as a whole. After a few years of making relatively sub-par films, McDonagh returns to his roots, evoking both his magnificent stage work and his masterpiece In Bruges (which includes reuniting with Colin Farrell and Brendan Gleeson, who give some career-best performances in both films), and he proves that he is amongst our greatest writers and directors working today, someone who can weave together poetry from the most paltry of premises. By far his most complex film to date, and the one that covers some of the most profound philosophical debates that have existed for centuries, The Banshees of Inisherin is a true masterwork.

Satire is not supposed to always make you feel comfortable – sometimes, it is enough to find a satire that just throws you directly into the deep end, and watches you gasp for air with a grotesque grimace that makes it clear how entertaining such a process can be – Triangle of Sadness is that film, and as arguably our greatest working cinematic satirist, Ruben Östlund brings his unique talents to the screen in a way that feels like he is continuing to challenge the boundaries of the medium, albeit from a distance. In his English-language debut, and the third in an unconventional trilogy of social satires (which also includes Force Majeure and The Square), tackles the upper class, the elites that view social media engagement as a precious commodity, and treat follower counts as some form of currency, perhaps not in a practical sense, but at least in terms of giving them the credibility that they all seemingly crave. Östlund is not one for subtlety, and Triangle of Sadness certainly is about as bold as it can be – but like any great satire, it uses its content to provoke thought, which is extremely compelling and wildly entertaining, perhaps with the exception of the people who subscribe to the idea that social media is not only a vapid tool for self-assurance, but a truly destructive force in the modern world. It takes quite an intrepid filmmaker to criticize subjects like this, but Östlund has always proven to be on the cutting edge when it comes to certain subjects, so it is hardly surprising that he would be such a proponent for scathing, grotesque and wildly entertaining humour that holds up a mirror to society and forces us to reflect on our own culpability in perpetuating some truly dangerous practices.

Some may look at Ricky D’Ambrose’s work as pretentious, or perhaps as if he was nothing more than a recent film school graduate who eagerly looked forward to showcasing the skills he learned in class. There are moments in his directorial debut Notes on an Appearance where this seems valid. However, for his sophomore effort, he produces something singular and visionary, a masterful account of a family undergoing changes that may not seem like anything out of the ordinary at the start, but are truly astonishing when viewed through the lens of his camera, which seems to pick up on the details that nearly every other film on these subjects seem to miss. On one hand, The Cathedral is quiet and poetic, a deeply intimate character study in which the main character is not a single person, but rather a family as a whole. On the other, it is a provocative and deeply unsettling depiction of trauma and psychological torment, which emerges from both those that surround us and from within us, showing that self-doubt and insecurity can cause indelible scars. D’Ambrose is one of the rare filmmakers working today who we can immediately tell is going to be a major voice in contemporary cinema, but where we also cannot predict the next steps of his career. He is a true original, a fascinating and visionary filmmaker that understands and appreciates all the details of his craft, and is willing to go to bat for every one of his ideas, even if it means challenging the status quo, both socially and artistically.

Few films are quite as simultaneously rewarding and frustrating as TÁR, in which Todd Field returns to filmmaking for the first time in nearly two decades, telling the story of a fictional conductor that stands on the precipice of being consolidated into history for her strong body of work, but who finds her life gradually unravelled by one misfortune after another, proving that you truly do reap what you sow. A challenging but bitingly funny film that is as much a character study as it is a ghost story (but where the spectres that haunt our protagonist are those that come from within), TÁR is an astonishing achievement, a disquieting and complex depiction of an individual heading rapidly towards a complete breakdown, solely because she is finally forced to take accountability for her misdeeds. Naturally, we cannot discuss TÁR without mentioning Cate Blanchett, who is as integral to developing this film as Field, working closely with the director to construct the character of Lydia Tár, and quite possibly turning in her finest performance, a portrayal of insanity, vanity and desire that can only be described as volcanic in terms of intensity. It is a powerful, compelling and quite unsettling examination of the human psyche, and a film that has enough depth to warrant every moment of our time.

Few artists have been more focused on the pursuit of the truth than Laura Poitras, who has dedicated almost her entire career to making films that pull back the curtain on the institutions that cause harm and suffering amongst the world’s population, as well as the people responsible for the power yielded by these organizations. Her most recent effort is a beautiful and poetic account of the life and career of Nan Goldin, who has been a steadfast ally to marginalized communities, using her influence as a celebrated photographer to explore the world and tell the stories of the invisible majority. The two artists come together and we see life as reflected through their duelling lenses, which eventually becomes as much about Goldin’s career as it is a harrowing portrait of the opioid epidemic that ran rampant throughout the United States for decades before finally intervention by the government, who many perceived as ignoring this crisis, because it mainly affected the groups that were not considered a priority for a country in which equality is apparently a foreign concept. Heartbreaking, shattering and truly extraordinary, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed paints such a vivid portrait of human suffering, but an even more powerful image of the resilience of the community, and how the process of amplifying voices for the sake of seeking change can make an impact eventually, even if it can be a long and challenging process with immense tragedies along the way. Few films have managed to be as profound and emotionally resonant as this one, a timely and haunting depiction of the human condition, captured by one of its greatest activists.

Despite being an exceptionally gifted filmmaker in his own right, François Ozon has never been afraid to make his inspirations extremely clear. He cites and references countless artists that have influenced his own identity as a storyteller – and throughout his career, the spectre of Rainer Werner Fassbinder has lingered heavily over his work, in terms of the style, genre and subject matter that the two individuals share. In his second adaptation of Fassbinder’s work, Ozon crafts one of his most ambitious films, a gender-swapped version of The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, which now tells the story of a repressed film director whose own desires and proclivities are both the source of his genius, and the cause of his ultimate downfall. As much of a reimagining of his idol’s work as it is an analysis of Fassbinder himself (with the main character quite obviously being based directly on the esteemed German provocateur), Peter von Kant is a triumph, which should hardly be surprising considering that Ozon brings so much passion and rigour to this story, which comes from a place of deep respect for Fassbinder, but not to the point where it is entirely reverential, since it doesn’t have any hesitation to showing the darker side of his obsessions, and how they played a part in his untimely demise. Denis Ménochet gives one of the best performances of the year as the titular character, and European arthouse legends like Isabelle Adjani and Hanna Schygulla (a previous collaborator of Fassbinder that had also appeared in the original film) help bring this provocative and deeply compelling experimental drama to life.

Watching the emergence of Owen Kline as a filmmaker must feel like witnessing the arrival of John Waters in the late 1960s. He is someone whose feelings of immense incredulity towards modern society have completely enveloped his work, to the point where we can’t feel anything but the most intense sensation of repulsion and despair – and every moment is absolutely brilliant. Funny Pages is not a film that announces itself as anything particularly noteworthy – it starts out as a relatively charming coming-of-age film, but as we begin to learn more about the characters that populate this world (including the protagonist, played brilliantly by newcomer Daniel Zolghadri), we start to feel a sense of unease, which only grows as the film progresses, until we are left with nothing but the most profound sense of discomfort. However, it is in these moments where some of the most revealing statements on the state of American culture, and the human condition as a whole, begin to manifest. No film from the past year inspired quite as visceral a reaction as Funny Pages did, and it proves itself to have so much more depth than we’d imagine based on a cursory glance. It also reminds us of how independent cinema is an incubator for some of the most abstract, outrageous stories that would not find a home anywhere else. Brilliantly dark and subversively funny, this film is as celebratory of the medium as it is critical, and this kind of engaging filmmaking is precisely why Funny Pages is far and away the most effective and fascinating film of the past year, and a film that may not have immediately made an impact, but will certainly be re-evaluated as time goes on, since this kind of unconventional genius very rarely goes unrewarded, even if it takes some time.

On that bizarre tone, that brings an end to our celebration of the best films of 2022, and closes the curtain on another incredible year for cinema. Every year, I find myself enthralled by the state of the industry – whether new work from established masters, or gems created by exciting new voices in cinema, the world of film continues to be surprising. In terms of both mainstream and experimental work, and in every conceivable genre from several different parts of the globe, there is certainly not any shortage of exceptional works being produced, which only makes being a film lover all the more exciting. I cannot wait to see what surprises 2023 has for us (and based on the first two months, it’s already shaping up to be a fantastic year), and while it is impossible to assess how strong a year was immediately, some distance will likely prove that this was yet another year in which the medium reached new heights, and proved that despite many obstacles, there aren’t any discernible signs that film is going out of style, and that it is being kept alive by a plethora of incredible artists, all of whom do exceptional work and embody the true magic of cinema.

Another Perspective

The Essential Films of 2022

4. Emergency

3. The Banshees of Inisherin

2. Women Talking

1. RRR