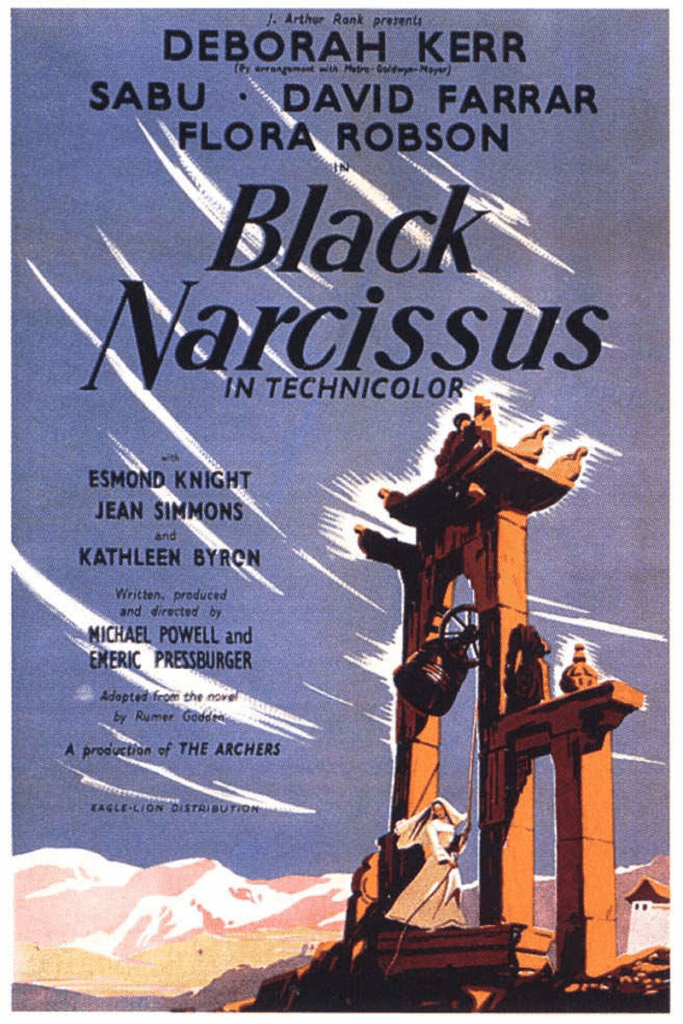

When it comes to discussing art, there is a great deal of discourse surrounding the debate between style and substance, with many tending to view it as a binary system, and one that an artist (regardless of medium) can only employ individually. If there was ever someone who could be considered to have mastered both in tandem, it would be the directing duo of Emeric Pressburger and Michael Powell, affectionately known collectively as The Archers. Their professional pairing over the course of nearly half a century (stretching from the outset of the Second World War, right into the early 1970s) brought out many magnificent films. They were gifted artists in their own right (Powell in particular having proven his mettle as a great auteur all on his own), but it was their collaborations that always brought out their best work – and while there may be a ferocious argument to what their greatest film may be, one of the prime candidates has always been Black Narcissus, their adaptation of the novel by Rumer Godden, which tells the story of a group of nuns living in a newly-occupied convent in the mountainous Himalayas, struggling with issues of identity and carnal desires, which they see as inherently against their faith-based vocation. A strikingly beautiful film that could legitimately lay claim to being one of the most gorgeously-made works of cinema ever produced, Black Narcissus is a staggering achievement that gradually takes its time to decode these characters, aiming to understand their predicament, all the while exploring the nature of desire, and how one responds to these forbidden carnal cravings, which serve to be the impetus for a truly fascinating drama.

Starting with the source material, we can see precisely why Powell and Pressburger would be intrigued by Black Narcissus. Godden was a writer with a clear interest in a range of subjects, but was particularly fond of looking at distant cultures – we’ve previously discussed her truly beguiling work in composing The River, which was the subject of a charming Jean Renoir drama that also inadvertently propelled the career of a young Satyajit Ray. This film is a different matter entirely – sampling from a similar social and geographical milieu (as it is also set in and around the Indian subcontinent, particularly in the mountain range that divides it from the rest of Asia), this is a much darker film, but not in terms of the cultural commentary, with the story remaining incredibly sympathetic and respectful to the natives. If anything, Godden’s work is built on critiquing (but not necessarily opposing) the colonial project, which is something that was already a source of contention, especially since this film was produced before India had gained independence from Britain, meaning that there was still a significant dominance of colonial power the lurked beneath even the production of this film. It may not have been filmed on location (which we’ll discuss in due course), there was a lingering sense of complexity to how Powell and Pressburger formed this story around ideas that were still incredibly contentious, and using Godden’s text as a starting point for what was to become a masterful and hauntingly beautiful analysis of this period was an incredibly wise decision that helped give Black Narcissus the necessary nuance and intricate understanding of the subject matter it required.

Several of the most iconic images from Black Narcissus capture the unforgettable sight of the cast delivering these stellar performances, which are ultimately some of the most evocative (and often quite frightening) portrayals of such characters we’ve seen. The idea of the deranged nun is one that has become almost secondary, with the growing disillusionment with religious order contributing to a gradual movement away from the sanctity of the faith, into one that is dogmatic and filled with deception. Black Narcissus is not a film that does much to change this perception, especially in how it constructs its characters – it does take a more critically-minded viewer to understand precisely what Powell and Pressburger were aiming to achieve here in terms of the people that ground the film, but it’s very clear to see that there was something simmering below the surface in every one of these performances. It features one of the first truly magnificent performances given by the incredible Deborah Kerr, an actress who occupies a strange place in our cinematic culture, being gifted enough to be a prominent performer, but whose sensibilities inherently veered towards more character-based work, meaning that she constantly stopped short of being a major film star, despite having the full potential. She’s one of our great performers, and if we look at her career in retrospect, she spent decades doing incredibly interesting work that rivals that of any of her contemporaries. Arguably, she is more of a reactionary in Black Narcissus, one of the only people in this convent who manages to retain a level head and remain logical in the face of growing tensions. She’s sharply contrasted by the rest of the cast, all of whom are playing characters that gradually descend into madness, particularly Kathleen Byron, who is absolutely unforgettable as the film’s main antagonist, a woman whose cravings eventually turn her into a cold-blooded psychopath, leading to one of the most shocking climaxes in film history, tying together a cast composed of some truly exquisite performers that manage to realize the depths to which they needed to go to convincingly tell this story.

However, as much as we’d be inclined to wax poetic about the incredible performances, anyone with the vaguest knowledge of this film knows that the true star of Black Narcissus is Jack Cardiff, whose cinematography stands as some of the greatest in film history. Powell and Pressburger had a keen attention to detail, and the visual splendour of their films was often the result of collaborations with cinematographers that could realize their vision without detracting from the stories. Cardiff’s work with the directors remains their peak, with his ability to capture every intricate detail being one of the primary reasons their work is considered to occur at the perfect intersection between the aforementioned style and substance debate. Black Narcissus in particular is a marvel – filmed in the United Kingdom, as opposed to on location in the Himalayas, everyone involved had the challenge of having to convince the viewer that we were seeing some remote destination, rather than a film set. Part of this comes on behalf of the production design, with the construction of these sets being absolutely incredible, so much that they don’t even realize we’re not situated at the very top of a mountain peak until the very end. It takes a lot of work to produce something that looks realistic, and Cardiff’s camera keenly prevents the illusion from disappearing entirely, with the artificial nature of the production being entirely concealed by his gorgeous cinematography. Even if we set aside the very compelling story, this film is still absolutely magnificent to witness on a visual level alone, and the stunning camerawork stands as some of the most spellbinding. It would be a challenge for even the most innovative contemporary photography to evoke such gorgeous and staggering images, and this is the primary reason why Black Narcissus has remained such an artistically resonant work.

Black Narcissus is a film in which the dissenting voices normally come across as intolerant or myopic, depending on where their criticism lies. This isn’t to say that it is a perfect film, but it is about as close as it could possibly be, especially in how the film gradually, and with seemingly very little hesitation, finds its way through the range of complex themes, all of which gradually manifest in these hauntingly beautiful, and often deeply disquieting, psychological thriller. It is an exceptionally simple film, and it is one that takes its time getting to a particular place, whether narratively or thematically – but the journey is one that is far from uncomfortable, and we know that the quality of work produced by Powell and Pressburger is always of an impeccable standard, so even when we may feel like we’re getting slightly lost in this nightmarish version of the world, we know that we are in good hands, as their artistic ambitions are bold and plucked from a place of undeniable curiosity. They explore the nature of desire in a way that is almost revolutionary – filled to the brim with gorgeous imagery and a story that is as complex as it is irreverent, Black Narcissus is an immense achievement, and one of the most well-formed films of its era. Once again, it may not be the definitive choice for their best work, but it certainly stands as one of their most enduring, and the fact that it remains as resonant and beguiling, over three-quarters of a century since its release, should point towards all the reasons behind its long-lasting success. Now, on its 75th anniversary, we can once again celebrate the incredible work that went into the creation of this film, one of the most unexpectedly brilliant works of literature from a time when such stories were seemingly taboo, both in terms of the representation of religion and desire, both of which are integral to the creation of this stunning film.