Slow cinema is an art form that very few filmmakers are able to master. Mike Mills is one of the elite group that have managed to build a career around carefully-measured, intricately-woven stories that take their time. They are certainly an acquired taste, since his films don’t immediately announce themselves as the most bombastic productions, but for those who are adherents to the current movements within the world of independent cinema, Mills represents a new class of American filmmakers who tell stories that feel so expansive, yet so deeply personal at the same time. His most recent offering is C’mon C’mon, where he places the viewer in the role of observers to a down-on-his-luck radio journalist who is tasked with looking after his nephew for what is supposed to be a very short span of time, but ends up last much longer than both parties expected. Simple but evocative, and told with the fervent dedication of someone who not only has something to say, but the singular vision to execute it in a way that feels like it is circling around major themes, the film is one of the year’s most exceptional achievements. Mills is the kind of filmmaker who is notoriously selective, choosing to space out his projects across several years, giving his films the sensation of being major events, especially since he has continuously proven that he embodies the concept of quality superseding quantity. While it may not rise to the heights of his masterpiece 20th Century Women, this is still a remarkable piece of cinema that is as poetic as it is heartbreaking, proving that Mills is one of our best living directors, and someone whose unique talents and remarkable vision regularly results in stunning works of bespoke artistry.

C’mon C’mon is a film that tells a story that comes from the heart, which is exactly what was to be expected based on the director’s previous work. Mills has developed into a filmmaker that centres his work around his own experiences – he may have a relatively small body of work, but each one of his films is one that is drawn from his life in some way, serving as a love letter to the people integral to his upbringing. Whether basing a story around his changing relationship with his father in his final years in Beginners, or paying tribute to the many women that were woven into his childhood (especially his mother) in 20th Century Women, Mills has a penchant for films about family – and here, we are introduced to a character seemingly standing in for his uncle. This is a unique dynamic, since it allows the director to put aside the more conventional and common discussions around the relationship a son has with his mother or father, and places the emphasis on a different kind of connection, one that is often extremely strong by virtue of the nature of the relationship, but opens up the possibilities for further discussions. The concept of an uncle or aunt is a peculiar one – they can be anything from distant relatives to surrogate parents, depending on the degree of closeness one has with them, which is what Mills is exploring here, looking at a young child’s growing relationship with a man to whom he is closely related, but really doesn’t know all that much about as a result of the distance between them – and throughout the film, we see the emergence of an unlikely friendship between the pair as they spend more time together, growing to respect each other through realizing that they have many more similarities than they initially imagined, and forming a lasting bond.

C’mon C’mon comes from a place of profound intimacy, and we can see Mills working laboriously to develop this story beyond that of simply a conventional story of two oppositional forces coming into close contact and finding that they share more common ground than they were led to believe. On the surface, the film seems like a relatively conventional film, the kind of endearing family-based drama that we often see produced in independent films, since there is a resonance that comes with these stories, since the vast majority of viewers can relate to these situations in some form, and the specific situations are highly relatable and not at all challenging in the traditional sense. However, Mills is not a director who necessarily aims to pander directly to expectations, and while his work is very well-constructed and enjoyable, it is drawn from a very personal place. While not autobiographical in the sense that he is directly telling a story that he has first-hand experience with, he instead forms a film around general ideas that he could relate to, and telling it in a way that does not alienate viewers. C’mon C’mon is not a film only about Mill’s uncle, but rather about every wayward member of one’s extended family that may stumble into your life at what appears to be an inopportune time, but actually turns out to be something of a revelatory moment, since they bring a particular quality that changes one’s perception. Perhaps this is veering far too close to cliche (and the similarities between this film and the delightful but otherwise trivial Uncle Buck are often very clear, right down to the presence of an actor shared between the films) , but Mills avoids it through simply telling a story that means a lot to him, by way of a film that he knows will mean a lot to the audience, who will likely find something of value here, even if we can’t relate to the exact narrative details. Mills is a tremendous storyteller, and his films are often multilayered affairs – but it’s his writing that stands out as perhaps his most remarkable talent, with his ability to weave together words making him one of the most fascinating filmmakers we have working today.

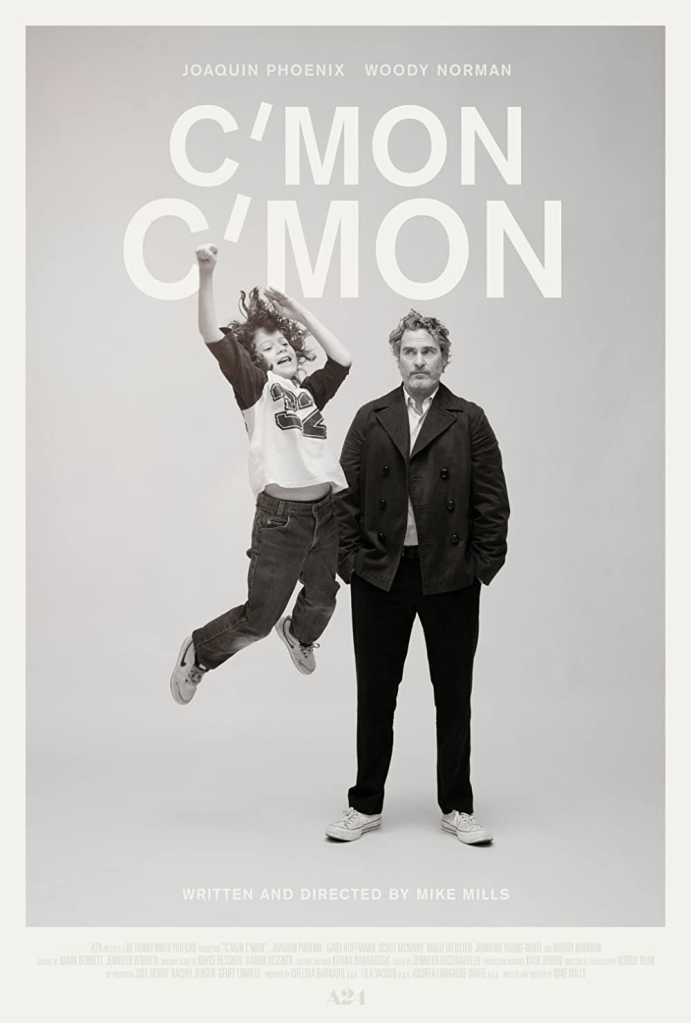

However, it wouldn’t make much difference if he didn’t employ incredibly gifted actors to take on the roles – and once again, he employs a solid ensemble to bring his characters to life. Joaquin Phoenix, who has ascended beyond any expectation to being one of our finest actors, takes a break from the more excessive roles he has been playing recently to portray Johnny, his most subdued role since Her nearly a decade ago. As this middle-aged journalist who is desperately grasping onto his youth, Phoenix is the embodiment of candour – he’s playing a character who is rough around the edges and deeply flawed, but embraces his imperfections, since he knows they don’t know him as a bad person, just not one that stands out in a crowd. He is sharply contrasted by the character of Jesse, a precious child whose intelligence and eccentricity makes him a worthy adversary for the more subtle Johnny, with whom he initially clashes, but grows to adore once they discover they have a shared worldview, just taken from different perspectives. Woody Norman is a revelation as Jesse, with every element of his performance being a clear deviation from the conventional, unremarkable tendency to present young characters as overly adorable. As a character, Jesse is not precious or a bundle of lovable quirks – he’s feisty and annoying, and is mostly a frustrating figure. Yet, the film never punishes him for this, since it was the entire purpose – as a young man trying to understand the world around him, he falls victim to his own insecurities, which is ultimately the root of his growing relationship with his uncle, who has been experiencing similar doubts about his own place in his surroundings. Gaby Hoffmann ties the film together as Phoenix’s sister, and the mother of Norman’s character, who serves as the central catalyst for the story, and weaves in and out of the film, playing a woman carrying the weight of the world on her shoulders – and the trio make for a formidable group that capture the spirit of humanity through interpreting Mills’ stunning and unforgettable characters.

Most of what allures us to this film is the promise of warmth, with the general theme being a family-driven drama that is propelled by nothing but emotion and atmosphere. This should immediately evoke a sense of caution in the viewer, since we have been conditioned to expect these kinds of stories to be overly emotional in a way that is riddled with cliches and conventions, and just looking at the general synopsis, it doesn’t seem like it would be one that would deviate too far from this tradition. However, we’ve come to expect more from Mills, and he absolutely delivers what he promises, by which he constructs a beautiful and meaningful drama that is certainly very emotional, but is not saccharine for even the briefest moment. The film does deal with serious issues, tackling conversations around death, divorce and mental illness, as well as the more abstract feelings of isolation and anxiety that many of us tend to experience as a result of this fast-paced world – but the director takes these themes and filters them through a very easygoing film, one that may not make light of these real issues, but rather emphasizes that, as challenging as they may be, they are simply part of life, and something that we all have to deal with at some point. C’mon C’mon almost feels like an attempt to pause the neverending stream of reality that tends to become very overwhelming, and instead focuses on the moments in between, those brief and fleeting emotional sequences that we don’t always remember, but which are fundamental to expanding on our perspective on the world. The film functions as a vivid portrait of everyday life, and the pared-down black-and-white photography captures reality in a way that is simple but stunning, and adds to the intimacy that defines the film and makes it such a beautifully poignant piece of humanity-driven storytelling.

C’mon C’mon is not a film about anything in particular. The general plot centres on a child and his uncle as they travel the United States, asking important questions, both internally and in conversations with other children, whose perspectives on life and the future are shown to be a lot more vivid than we’d expect from a group that is normally seen to have a very simple understanding of real-life issues. Mills is a director who seems to have a genuine interest in developing characters beyond the point of archetype, which is mainly a result of the fact that many of them are created from fragments of his past, pieced together from people he knew and loved, which ultimately leads to the compassionate view of the world that is regularly found in his work. There are few filmmakers whose vision is both as realistic and hopeful as Mills – he’s part of an elite group of storytellers who has an optimistic outlook, albeit one that is always consistent and never unrealistic. He simply sees the beauty in everyday life, and acknowledges that around every grim situation, there is a silver lining. C’mon C’mon is a film that takes its time to get to a particular narrative point, and even once it has found a specific angle, it doesn’t adhere strictly to it, instead using the story as the foundation for its atmospheric meanderings through the lives of these characters. It’s an incredibly poignant film, one that has a degree of sadness simmering beneath each interaction, but also a sense of genuine hope – it has a happy ending, one that actually means something rather than just existing to conclude the film. It’s an absolute triumph of a film, and further proof that Mills is a director capable of drawing out the most authentic emotions and heartwarming stories in his perpetual search of meaning, which makes his steadfast celebration of the human condition all the more powerful.