Just based on the premise, one would be forgiven for thinking The Story of Qiu Ju (Mandarin: 秋菊打官司) is not a film we should take particularly seriously – after all, it does centre on a man being kicked in the groin after a heated argument with their village chieftain, and his heavily-pregnant wife taking matters into her own hand and going out in search of retribution for her mildly-injured husband. going as far as taking legal action against the perpetrator. It almost seems to absurd, especially considering the film is written and directed by Zhang Yimou, who adapted it from the novel by Chen Yuanbin. Zhang, who remains one of the most celebrated and important filmmakers in the history of Chinese cinema for his relentlessly poignant and meaningful investigations into different moments in his nation’s history, is someone whose work has always been fiercely acclaimed, so much that it doesn’t take much for us to give him the benefit of the doubt with The Story of Qiu Ju, which is a continuous success, working through the slightly more strange subject matter. This film is constantly working towards uncovering the fascinating themes embedded in the story, and deconstructing them to the point where, putting aside the humorous storyline, we’re presented with a daring and provocative social drama that is never content with leaving any details up to the viewer’s imagination. The film is constantly helping the viewer along every step of the way, explaining the more abstract concepts and emerging as one of the more delightfully irreverent dark comedies of its era, while still carrying an emotional heft that should not be underestimated, just like the rambunctious protagonist at the heart of its story.

The Story of Qiu Ju represents the director at his best, doing what he knows how to do, and weaving together a ferocious but deeply moving story of China through his perspective, which has always been one of the primary reasons behind the director’s success behind the camera, since he perpetually manages to explore his nation’s past and present with a kind of candour that we don’t often find so strongly represented in the oeuvre of many other filmmakers. His prolific career has seen Zhang navigate thousands of years of Chinese history, whether it be looking at the height of the various dynasties that ruled the nation centuries ago, or a more modern approach, where he offers perspectives into contemporary issues facing China and its people. In The Story of Qiu Ju, he is questioning the bureaucratic process through positioning the story around a painful but otherwise minor event, and the vengeful woman involved in exacting vengeance on the perpetrator, gradually showing the extent to which someone can be willing to go to find justice, even if it is for something that ultimately doesn’t have much legislative or cultural meaning. As a result, Zhang correctly leans into the more humorous side of the story – not only does the decision to make The Story of Qiu Ju give the film a more entertaining edge, it allows Zhang the chance to comment on deeper subjects without needing to focus on more complex issues. Had the crime at the heart of this film been even slightly more serious than a minor case of assault, it’s unlikely that there would’ve been as major an impact made, since every frame of the film depends on Zhang surrendering to the comedic side of the story, and finding the depth within even the most absurd and far-fetched narrative details.

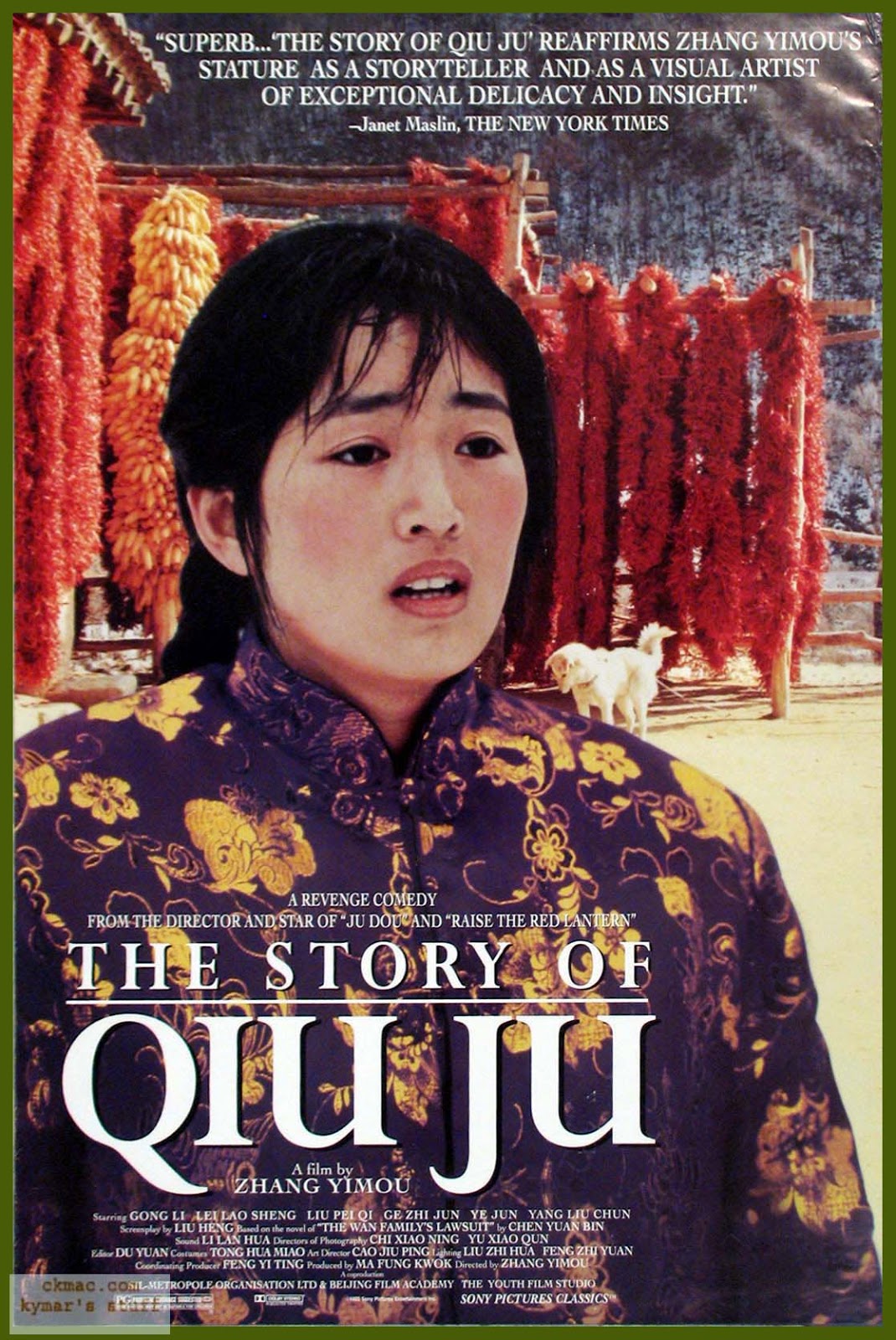

As with many of his films, Zhang is working with Gong Li, who holds a similar level of cultural cache when it comes to iconoclasts of Chinese cinema. A gifted actress regardless of the director she is working with, Gong has consistently turned in her best work while under the guidance of Zhang, who essentially helped establish her as one of China’s most important actresses, and somehow who remains a globally-recognized icon in terms of her incredible skills. Zhang gives her one of her best roles in the form of the titular heroine in The Story of Qiu Ju, where she puts aside the more aloof, innocent roles she played prior, and instead takes on a more spirited character in the form of Qiu Ju, whose undying compassion is only challenged by her tenacious desire to find justice, which is only made more intense the more she finds herself turned away. It takes a lot to portray someone whose only desire is to get an apology, so much that she is willing to elevate her grievances to the highest courts to which she has access, but Gong is gifted enough to play such a character, pulling the film out of middling absurdism and actually delivering a spirited performance. It’s hardly surprising that this is considered some of her most cherished work – its a complex and nuanced performance that not only allows Gong to make use of her exceptional talents, but also draws attention to her unique expressivity and ability to tell entire stories with even the most subtle movements and gestures, which work in conjunction with the film to tell of her exploits – after all, the film is named The Story of Qiu Ju, so it would only make sense for her performance to be one strong enough to carry the entire narrative, and while the role in itself was interesting enough to warrant any actress turning in a great performance, only Gong could have found the internal nuances of the character that make it as compelling as it ultimately ended up being, which is far from an easy task.

Its often been argued that the best way to discuss a serious issue is through making a comedy – we’ve seen some of the most impactful social statements and examples of a meaningful discourse delivered through the guise of humour, whether smart satire or broad slapstick. There is something about delivering a stark message in a form that makes the viewer laugh that has always been so extremely interesting, since we do tend to react more strongly to humour than we do to more heavy-handed emotions. The Story of Qiu Ju has quite a sobering story, but it’s done in such a way that it never feels as if we are being subjected to needless preaching by a director who simply wants to convey the more bleak message at the heart of his story. Zhang doesn’t often peddle in comedy (in fact, this is one of only three or four films that the director made that have actively been classified as comedies in some form), so it makes sense that The Story of Qiu Ju wouldn’t be a bombastic, outrageously funny work – but it has a lighthearted earnestness that pushes the story along, the levity mainly coming from the deliriously strange event that serves as the impetus for the main character’s journey, and the increasingly absurd lengths to which she goes to acquire justice. In many ways, The Story of Qiu Ju plays like a more softhearted, simple version of a Franz Kafka story, where a peculiar event kick-starts a deep and often hauntingly bizarre voyage into the heart of the bureaucracy – and right at the heart of this story resides this keen sense of humour, which Zhang makes sure to use sparingly, waiting for the right moment to infuse the film with a dash of heartwarming laughter, which sharply contrasts with the more disquieting representation of Chinese society.

Much of what makes The Story of Qiu Ju so compelling isn’t strictly the way Zhang uses humour to tell his story – instead, it comes from the balance of the comedy with the more sobering social angle that defines the film. The production of the film entailed the director secretly shooting some portions of the film (mainly street scenes set in the larger cities visited by the main character), as it was difficult to acquire official permission to do so, which is clearly not something that the director was willing to pursue. This method interestingly contributes to the broader conversation, since looking slightly beyond the story itself, which is focused on a single woman’s actions, and instead focusing on the broader socio-cultural milieu reveals much about the society in which Zhang was working. The film exists outside of time and space – it is never specified particularly when it takes place (and the exact location within China is also never directly mentioned), and the scenes set in the village imply that it could’ve taken place at any time. Contrast this with the bustling urban centres in which Qiu Ju constantly finds herself, and you’ll see how interesting this comparison is, and how the director effortlessly weaves together two wildly different perspectives, implying that there are many radically varying interpretations of one nation, and how different individuals perceive their environment differently. This is embedded deep within the story, and Zhang never wastes any time in trying to justify this angle, instead working towards a very pointed but tender critique of the society, commenting on major issues, but from a more endearing perspective, making bold statements without being impelled to be the definitive voice on any of these issues, which only serves to make The Story of Qiu Ju all the more alluring and interesting as a piece of social commentary, one that carries a lot of meaning beneath its unassuming exterior.

There are many reasons behind Zhang being considered one of the greatest voices in Sinophone cinema – his films are all impeccably-crafted, and regardless of their temporal or geographic setting manage to hold both emotional and artistic resonance, which is not something that many filmmakers are able to easily achieve, especially not anyone as prolific as Zhang. The Story of Qiu Ju is one of his most endearing films, not only because it is the rare comedy he made, but also the very personal nature of the story. This is not a sweeping historical epic, but rather an intimate, character-driven film that pays attention to the smallest details in addition to the broader concepts that set the foundation for the film. The anchor of the film is certain Gong Li, who is delivering a nuanced and captivating performance that feels like it is even more carefully calibrated due to the quirks she had to weave into her portrayal of this ordinary woman seeking retribution for an event that may have been harmless, but did bring physical and psychological harm onto her family, and for which she believes the perpetrator needs to be punished. As a whole, The Story of Qiu Ju is excellent – its charming, irreverent and a lot of fun, but contains depth that would otherwise not be present had this story not been placed under the care of some very gifted artists who have always stood as stalwarts of their national cinema, and which deserve all the praise they have received over the decades, not only for their artistic talents, but the wonderful dedication they have to their craft, which has never been more potent than in this film, which proves that some of the most compelling stories come in some unexpected forms.

The partnerships of a director and his muse result in particularly rich cinema. Woody Allen and Diane Keaton. Ingmar Bergman and Liv Ullmann. Federico Fellini and Giulietta Messina. John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands. Jules Dassin and Melina Mercouri. Joel Coen and Francis McDormand. Woody Allen and Mia Farrow. And Zhang Yimou and Gong Li.

This Golden Lion winner serves as a particularly strong example of the artistic collaboration of Zhang and his Volpi Cup winning lead actress. In this particular time period, the two made six films together that were characterized by their exploration of how individuals addressed a challenging political environment. The Chinese films grew more bold in their adverse political voice till Zhang and Gong’s celebrated epic To Live was banned by the communist government and the two prevented from making films for many months.

Beyond a wealth of political subtlety, the humanity in this film is rich and deeply involving. The Story of Qiu Ju is highly recommended.