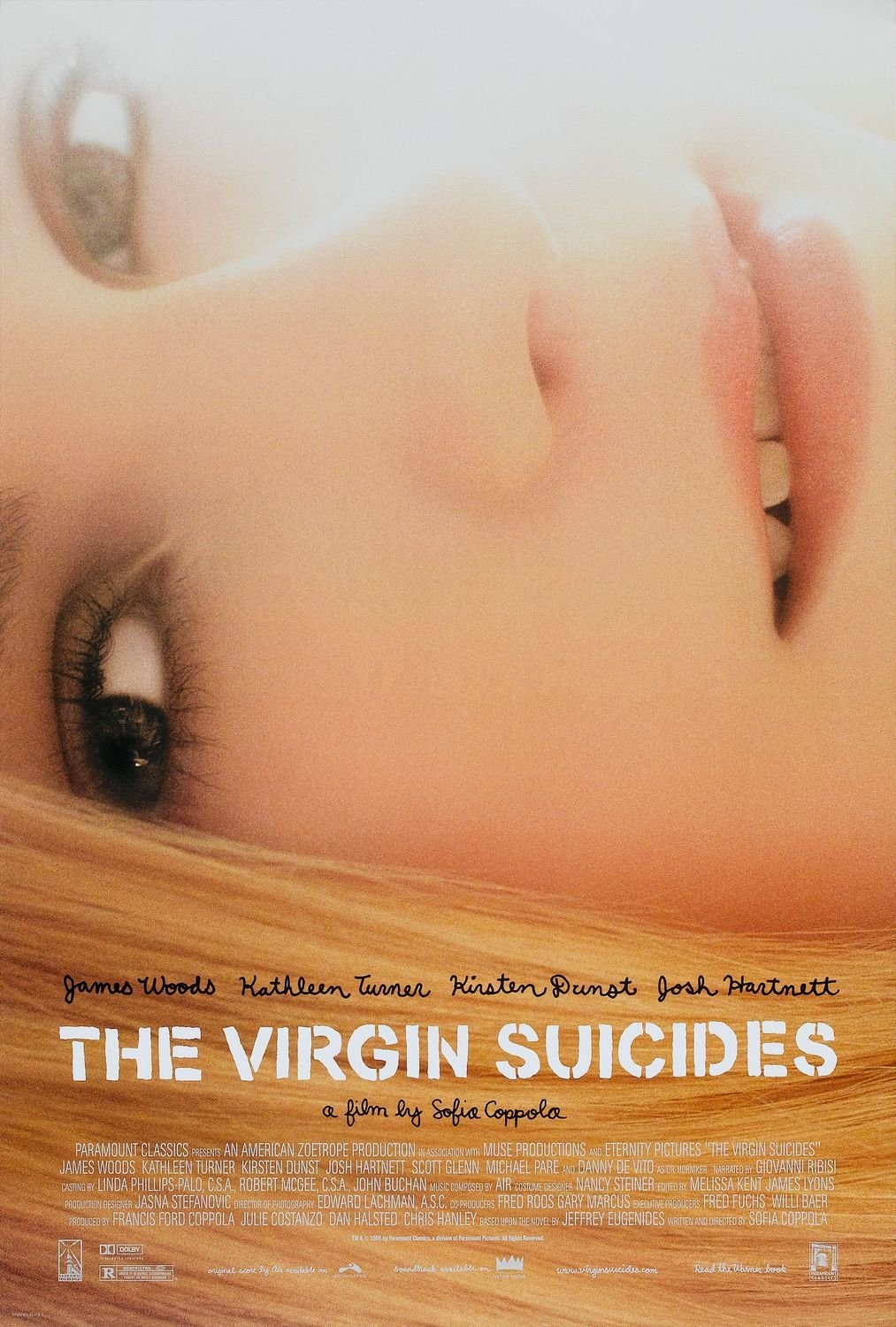

As the adage goes, if at first you don’t succeed as an actor, try and become a world-renowned independent filmmaker. Sofia Coppola has had a fascinating ascent, going from the victim of derision for her undeniably poor work in The Godfather Part III, to changing gears entirely and taking up a secondary career as a filmmaker, which is where she find her niche and established herself as a powerful voice in the industry, right at the time when her vision was more necessary than ever. Her reputation changed from the shameless child of nepotism, to a brilliant filmmaker almost immediately, right as she picked up a camera and adapted Jeffrey Eugenides’ brilliant The Virgin Suicides, which not only served as her directorial debut, but her entry into the culture as someone who was going to make her home in the director’s chair, her acting career almost entirely left behind in pursuit of the more serious work behind the camera. It’s not necessarily her best film (how often does someone’s debut define their career, at least in terms of those who weren’t one-hit wonders but established filmmakers?), but like anything else produced in this notoriously strong year for cinema, The Virgin Suicides is a fascinating, intelligent and groundbreaking work of fiction that introduces audiences to an exciting new talent, and gives us the chance to see a work by one of the most enigmatic writers of his generation brought to the screen, which Coppola does with tact, sincerity and a revolutionary style that immediately makes this a film worth seeing, even if only to see where her roots as a filmmaker lie, and how far she has come since deciding to pursue a passion project, which eventually kickstarted her entire career as a filmmaker.

The Virgin Suicides is not the easiest film to adapt to the screen – without even having read the novel, one can figure out that it wasn’t conceived with any aspirations of adaptation. Eugenides is infamous for his dense prose, which is compelling but challenging, which is why not much of his work has found its way to the screen. In fact, to date, The Virgin Suicides is his only work (whether novel or short story) that has actually successfully come to fruition, with the decades-long attempts to adapt Middlesex floundering just as fast as they’re pursued. There’s an admirability that comes when we realize how Coppola’s passion for this novel was so strong, she successfully lobbied to have her version produced (rather than another studio that had already bought the rights and commissioned a screenplay), right at the start of her directorial career. Inarguably, her last name must’ve had some substantial part in swaying investors, but unlike many other individuals that use their familial influence to get ahead in the industry, Coppola did something effective with this new wealth of respect, and turned in a masterful work that is partially responsible for a new movement of independent cinema overall, part of a growing group of young, urban filmmakers who told stories from their own unique perspective, forcing the industry to adapt to their vision, rather than the other way around. For all these reasons and more, The Virgin Suicides is yet another entry into a strong year of cinema, and in many ways could legitimately stake a claim to being one of the very best from that crop of films.

From the first moments of The Virgin Suicides, we know that something is amiss – and credit must go to Coppola for retaining the ethereal spirit of Eugenides’ novel. Anyone who has experienced the translation of notably complex authors to the visual medium will tell you that it’s not a seamless process, and one that is rarely successful without an enormous amount of work. Some novels are simple uncinematic, and they don’t lend themselves to the visual form, relying on the reader’s ability to construct these worlds in our minds. Making something so abstract into a palpable series of images can sometimes be a fool’s errand, since much of the meaning ends up being lost by the end of it, the most intricate aspects neglected in favour of what is easier to show on screen. Coppola manages to get to the core of what made this novel so special, and focused intently on those aspects, ignoring the preconceived conventions that guided literary adaptations at the time. This was both a liberating approach, as well as a burden, since it’s admirable to be so audacious, but being able to put these ambitions into practice is another matter entirely. Ultimately, this version of The Virgin Suicides is a very simple way of looking at the author’s major themes, filtered through the profoundly moving and provocative lens that was facilitated by independent cinema. A film like this didn’t need to sell itself as some crowd-pleasing sensation, but rather a minor arthouse masterpiece that would find its way into the minds of those most likely to appreciate it for what it was. It takes a great deal of fearlessness (as well as the knowledge that failure isn’t as much of an obstacle for Coppola as it would be for a director from a less affluent family), and it ultimately works to this film’s benefit that the director didn’t once attempt to fit this into a category that it didn’t really belong in, going her own direction entirely, and it all paid off.

For someone expecting a film that is more traditional in how it explores its themes and resolves the crises that serve as the basis for the dramatic tension, The Virgin Suicides is bound to be frustrating – nothing quite makes sense in this story, mainly because it seems to exist in a version of our world where not everything can be explained, and Coppola certainly doesn’t try and offer her own interpretation of the material. Everything in this story is told through memory (the use of multiple unnamed characters as the main perspective, rather than one of the protagonists, is inspired), and seems to be taking place through the foggy lenses of unsettling nostalgia, the kind that doesn’t impel us to think on the past fondly, but rather remember on occasion, hoping to find some understanding of what one experienced during the proverbial “good old days”. For this reason alone, The Virgin Suicides is a very challenging film, and takes some time to get fully accustomed to. However, for those who can find their way onto this film’s wavelength, and who can appreciate that not everything introduced in this story is going to have a neat resolution by the end, it’s likely that there will be a much more positive response, since this is a film that rewards a more open-minded perspective. Coppola understands that a story like this is driven less by narrative and more by atmosphere – and even when there are some prominent actors scattered throughout the film (with the likes of Kirsten Dunst and Kathleen Turner doing career-best work), the focus isn’t on their specific performances, but rather what they represent. The human aspects of The Virgin Suicides seem almost superficial in comparison to the intricate plotting done by Coppola in setting a particular mood – and it creates such a vivid, mysterious sensation, we sometimes forget that what we’re watching is a piece of fiction.

The Virgin Suicides is a film that immerses us into a world unlike our own, while still creating an image of it that is so incredibly recognizable. A work of unimpeachable humanity, where the psychological torment of those who experience the dreadful suburban ennui is explored beautifully, Coppola’s work here is truly impeccable. It takes a lot of effort to create something so vivid in how it represents the middle-class malaise that has never exited the public consciousness, only being concealed under layers of suppressed emotions. Yet, through her intricate understanding of the material (in itself not a feat that should be underestimated – kudos must go to Coppola from the outset for actually taking the risk to adapt an unfilmable novel and turning it into something profoundly cinematic), and her intrepid ability to weave it into something that feels so compelling, even when it is intentionally bewildering and difficult to watch, the director creates something thoroughly unforgettable. Thematically complex, narratively profound and executed with a deft precision that usually only comes about as a result of a rambunctious young filmmaker going for broke and trying out their hand at an audacious project from the outset. However, in the case of Coppola, not only did this start her career off on an impressive foot, but set the standard for much of what she was going to do throughout the rest of her career, in which she frequently set out to explore the human condition through telling compelling stories, and showing us a different side of society each time. Stunningly made and intimate in the way that only the best artistically-resonant stories are, The Virgin Suicides is a masterpiece, and a worthy addition to any conversation on the merits of independent filmmaking.