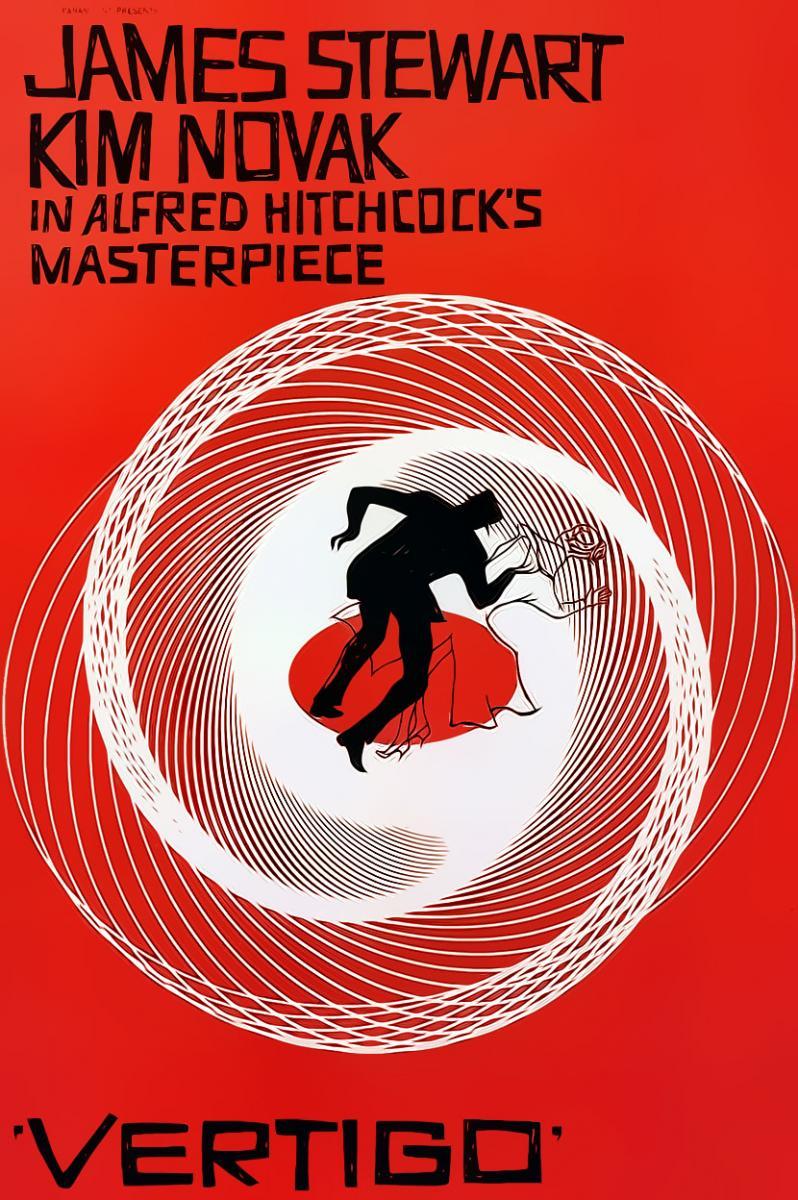

Most of the time, I tend to avoid discussing situations where a film has achieved the status of being considered one of the greatest of all times, because it would normally come down to reiterating many of the same points that others have made about why this particular work deserves the title, or it will be needlessly contesting a genuinely beloved work of art, which can sometimes come across as unnecessarily contrarian. However, there are certain cases where one can’t avoid looking at a film’s status in the process of discussing its status in the medium. Vertigo is perhaps the most difficult film to talk about in this regard, since not only is it a great film in its own right, but it develops a reputation as a masterpiece of cinema that stands beside many of the qualities that got it there in the first place. Over the years, it has inched higher up in the Sight & Sound‘s decennial rankings of the greatest films of all time, finally achieved the top spot in 2012 (with all signs indicating that it will hold on for another decade when the newest edition arrives next year), and has frequently been considered not only one of the definitive works of its era, but an incredibly influential film that impacted the entire medium at a time when it was caught at a crossroads between tradition and revolution. Alfred Hitchcock is not a filmmaker who is underpraised in any way, and he’s certainly received an endless amount of acclaim, often being considered the industry’s greatest contributor. Neither underpraised nor overpraised, but loved just as much as it should be, Vertigo has aged extremely well, being as refreshing and thrilling today as it was in its original release – and the elegant methods of telling this story, despite its grim subject matter, all go towards demonstrating the unhinged genius that Hitchcock possessed, and was willing to employ at key moments in the process of telling this twisted story.

The challenge that waits for anyone who dares to write about Vertigo is quite clear: how does one overcome these obstacles and say something that hasn’t been said already? The answer isn’t nearly as obvious, but perhaps the best approach is also the most simple – if we strip away the praise heaped on this film, the reputation it has garnered over the past six decades, and every bit of acclaim that is associated with it, and look at it as a piece of storytelling, the reasons for its brilliance are quite obvious – this is a masterful work of psychologically-charged mystery that is beautifully-made, written with conviction and executed by a director who was fully in command of his craft from beginning to end. Vertigo is one of the few canonical masterpieces that doesn’t only live up to expectations the first time around, but every subsequent viewing brings with it new details that we may not have noticed before, evokes another series of discussions, and unveils new ideas that come as a result of engaging with the film from different angles, looking at even the most minor details through a lens of discernment that is incredibly helpful when watch a Hitchcock film, since there is an atmosphere of intelligence hovering over these stories that only bolsters the experience. There is something new to be gained with every subsequent rewatch, which is rare for even the most inventive films, and only further proves that Vertigo unabashedly earns its place in the canon of essential works of cinema.

Not necessarily the kind of artwork that comes with a preconceived method of understanding it, but rather one that rewards a viewer who can take the basic premise and apply their own interpretation and understanding to the material, Vertigo is an immersive, provocative work of fiction that gives viewers something many other films struggle to do, especially those that use this film as a general guideline: it provides us with an experience, rather than just passive entertainment. This film feels like passively watching events transpire on screen, and more of a chance for us to actively become involved with the story – like Scottie, we are observing the strange events going on around San Fransisco, watching the mysterious femme fatale go about her daily life, while gradually inching closer and breaking that boundary of voyeurism, and becoming involved in a demented plot. We become a part of this story, and the intricate details we find along the way become valuable, since we are piecing together the mystery alongside the main character. Obviously, the film isn’t so immersive to the point where we guide the story, but the filmmaking is so hypnotic, we lose ourselves in this world – and as we’ve seen through his many films, the world Hitchcock evokes is simultaneously terrifying and enticing, so the idea of venturing into it once again should be frightening and terrifying for every viewer, since we never quite know what to expect – and part of what makes a film like Vertigo so iconic is because we all find different ways to look into it. Whether we want to see it as a straightforward psychological thriller, or as something deeper, such as an allegorical glimpse into the darker recesses of society, or even a manifestation of the fears intrinsic to the human condition, is all up to our own interpretation, and its certainly not unheard of to encounter several of these ideas, working in stunningly effective symbiosis, along the way.

The director didn’t earn the epithet “The Master of Suspense” without reason, and Vertigo does very little to prove anything less. Hitchcock takes us on a journey that would be easily considered enchanting if there wasn’t a genuinely terrifying sense of dread that accompanies it. The director’s ability to extract the most visceral reactions from his audiences (across all decades) without ever resorting to anything even vaguely excessive or inappropriate, is an enormous testament to his skillfulness, especially in how he clearly understands that setting a particular mood is just as effective in unsettling viewers, and that a film doesn’t need to explicitly explain its themes when the spirit of the film is disconcerting enough already. Every moment of Vertigo is formed in such a way that we know just enough to not be confused, but are essentially venturing into unchartered territory, where anything can happen. Twists and turns abound throughout this film (as should be expected from Hitchcock), but they all feel genuine and important, rather than being there for the sole purpose of confounding the viewer. Hitchcock rarely (if ever) baulked at the opportunity to infuse his films with an insatiable sense of mystery, and even when he was functioning at his most intentionally vague, his work is never frustrating, since we know there is purpose to the ambiguities, and that the payoff will be worth every moment of confusion. Delightfully twisted, but in a way that is active and purposeful, the premise of Vertigo makes wonderful use of some deep psychological concepts, such as doppelgängers, crises of identity, and the value of reconsidering the past as something that isn’t always as consistent as our memories make it out to be. There are layers to this film that hint at some disconcerting ideas, each one executed beautifully by a filmmaker with a real sense of sophistication, regardless of the work being done.

Ultimately, this was less of a review and more of an attempt to jot down some general ideas of what Vertigo means to me, as someone who encountered the film (and Hitchcock) at a relatively young age, and found myself captivated by how brilliant it managed to be. There really isn’t much need to critique this film – it is almost entirely without flaws, and what minor shortcomings it does have are easily surpassed by the raw, ambitious scope of the project as a whole. Vertigo is a film that means quite a bit to many people from several generations, and has been upheld as an unimpeachable classic since its release decades ago. Yet, the impact this film has made doesn’t preclude it from being an incredible work on its own terms – removing its status, and looking at it directly, we see what a well-formed, intricate and compelling thriller it is, led by one of the greatest actors of all time (with James Stewart being the perfect person to usher this film forward, his blend of everyman charm and ability to show incredible depth making Scottie a truly compelling character, and Kim Novak matching him beat-for-beat as the doomed femme fatale), and executed with precision by a director who knew how to find the perfect balance between showing restraint and surrendering to the inherent madness that underpins the story. In no uncertain terms, Vertigo is an absolute masterpiece – and the process of outlining the multitudes of reasons why it deserves such a reputation would take far too long. Perhaps it’s lacklustre writing, or the inability to say something new – but when it comes to a film like Vertigo, there sometimes isn’t anything that one can add, other than reaffirming why it is such an impressive work. Hypnotic, complex and just brilliant in all the ways that make a substantial difference, Hitchcock truly defined why his work has become the gold-standard for cinema, which doesn’t seem to be changing anytime soon.

Vertigo was received with shrugs upon release. Since then, film critics piled in the misunderstood classic bandwagon to promote their own self interest and advance their careers. Hitchcock explored his interest in duality with much greater artistic success in Strangers on a Train, Shadow of a Doubt, and Psycho. The special effects to help audiences appreciate the symptoms of vertigo are dated. Hitchcock famously blamed his leading man for the failure of the film. He thought Stewart was too old for a believable passion with Kim Novak. Stewart and Hitchcock never worked together again.

The admirable points of Vertigo make a short but compelling list. Hitchcock clearly fell in love with San Francisco. The City By the Bay is the true star of the thriller. The long takes of cars traversing hilly streets and breathtaking vistas of the skyline and San Francisco Bay are still strongly alluring. For those of us who lived during that era, the film is a postcard from long ago for a place that still lives so memorably in our recall. The cinematography here is astonishing.

The other highpoint is Bernard Herrmann’s magnificent score. The manner in which the music swirls and circles within itself is a far more imaginative exploration of the experience of vertigo than the cheesy special effect Hitchcock employs.

Thank you for these comments. I wanted to speak about all of them, but once you start getting into the nitty-gritty of a film like Vertigo, its impossible to stop!