Querelle is a bloated, pretentious and incredibly convoluted mess of a film – and it’s one of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s greatest achievements. Not normally a film discussed outside of the context of being the director’s final work, it is something that appeals more to those interested in looking at Fassbinder’s oeuvre in more detail, than it is a film that normally stands independent of its cultural context, which does a great disservice to a work that rewards patience and proves that his career ended on a particularly strong note, even if it is sometimes unrecognizable from the films that defined him as a truly original artistic firebrand. Drawing inspiration from his very peculiar approach to telling stories and getting his message across in a precise and authentic manner that is both drawn from innumerable cultural sources, and distinctly his own style, taken from his endless well of artistic curiosities that inform his vision. Querelle is more of a trivia item, a footnote on a career of one of cinema’s finest provocateurs – but putting aside the specifics of its creation, and instead focusing on it in comparison to how the director was developing his style and making a name for himself in an industry that had always been belligerent to his particular methods of storytelling, we can easily see how his loose adaptation of Jean Genet’s Querelle de Brest is a masterful work of both incendiary fiction, and an essential entry into the canon of alternative queer cinema, of which Fassbinder has always been one of the most fervent representatives. It may pale in comparison to the films the director was making during his peak, and its flaws may appear to come from some serious artistic miscalculations – but when it is stripped of its reputation and the other external factors that are normally associated with it, it’s not difficult to see how this was one of Fassbinder’s most promising works, and a hint at the fact that, even after nearly two decades in the industry and over forty films, that we was capable of so much more, and was only just starting to demonstrate his endless depth, which seems odd to say about an artist who defined the very concept of an iconoclast.

It seems almost poetic that a film that represented the most considerable movement forward, in terms of both narrative and form, is the one that ended the director’s career. To say Querelle was an evolution seems inappropriate, since Fassbinder was always challenging conventions and testing the boundaries of the format in new and imaginative ways. However, this was a film that saw him venturing into unchartered territory – working with more recognizable names in world cinema, attempting to adapt a legitimately adored text, and experimenting with his style in very unique ways – and for that reason alone, Querelle stands out as something of a reinvention for a director who relished in his refusal to commit to conventions, and the beginning of a new stage in a career that had to be brought to an abrupt (but sadly not surprising) conclusion, which seemed to be inadvertently hinted at throughout this film, even if only in terms of the underlying melancholy that existed as a constant theme that Fassbinder was exploring here, constantly uncovering new layers of longing relating to homoerotic lust and the carnal desire that is so often subjected to brutal censorship or outright elision in works that attempt to be more placid and conventional. As we have come to learn, the constant refrain of never playing by the rules is important when approaching Fassbinder’s work – with the exception of a few brief moments when he underwent a journey into something more conventional (but only in his terms – works like Despair and Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day may be somewhat departures from his more notable approach, but are still produced with his distinct authorial voice), he perpetually engaged in the challenge of pushing the envelope – and while it may sometimes feel as if he is meandering too much throughout it, Querelle is one of the best distillations of his style, being just as debaucherous and transgressive as we’d expect from the director adapting a work known for its visceral approach to the human condition – and there are few people better-suited to this material than Fassbinder.

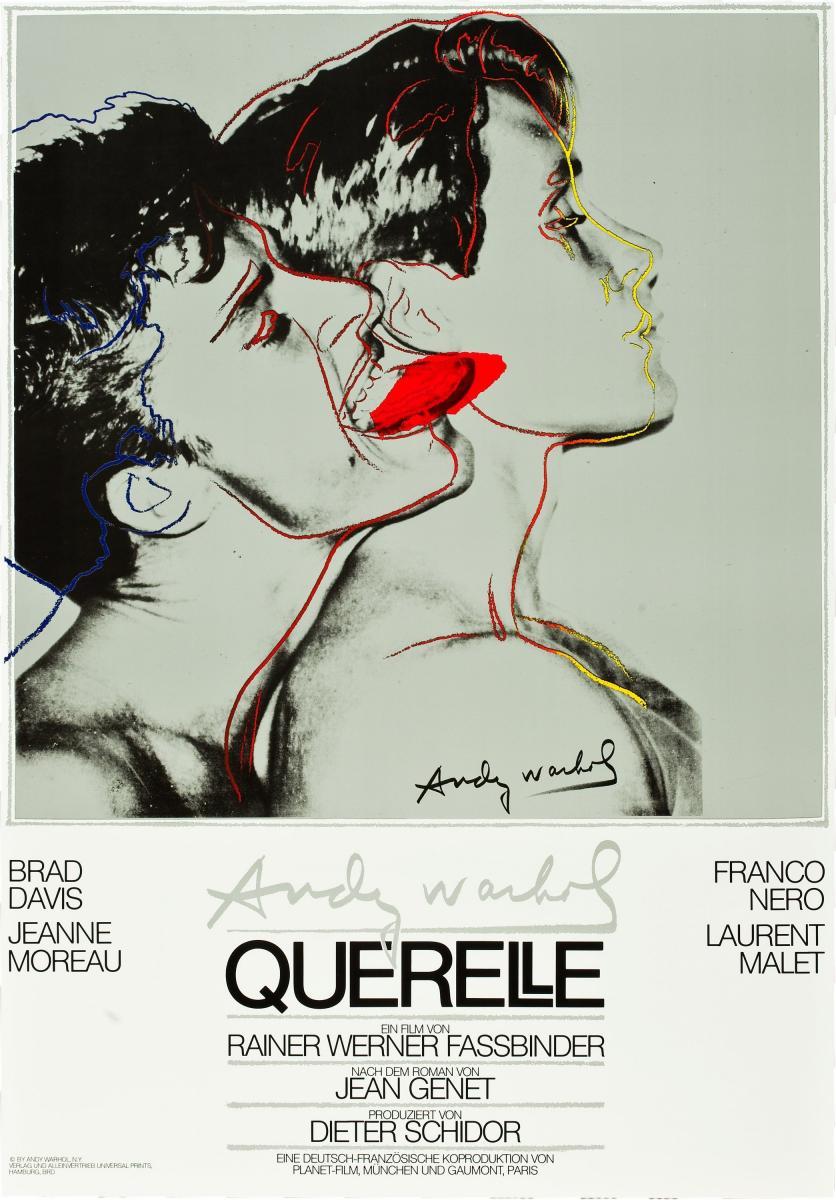

Querelle is clearly influenced by some of Fassbinder’s artistic heroes, particularly in how it operates visually. The film takes place in a dream-like Warholian landscape (with the growing professional and personal friendship between the director and the iconic artist undoubtedly being a significant factor in the creation of the film), and therefore sees Fassbinder working with a very distinct visual palette that draws allusions to the concept of Warhol’s iconic breeding ground of underground talent, The Factory – filmed entirely on sets in what appears to be a large warehouse (which is admirably not concealed, with the film using its resources in endlessly creative ways), and made to appear like a warped stage play with only the necessary components of a scene included, the film is quite a spectacle on its own terms, and even putting aside the tricky narrative content, there is still value in how the film approaches the artistic process on a purely creative level. Therefore, through taking his cue from Warhol, Fassbinder effectively infuses every frame of this film with a very peculiar artistic resonance, playing with the format enough to produce something quite remarkable, while not deviating too far from his more notable qualities as a director, making this both an incredibly experimental work, and one that is unabashedly the work of one of cinema’s most fascinating troublemakers. Fassbinder is ultimately one of the few filmmakers who could legitimately make a film that was the epitome of style over substance, and not have it perceived as a shortcoming, or an indication that he is any less of a filmmaker because of his proclivity to over-the-top splendour and an atypical manner of weaving stories together, which may alienate viewers not accustomed to his anomalous methods, but will only endear him to those who appreciate his abnormalities and find them to be the most enduring aspects of his endlessly folkloric legacy.

However, one mustn’t let the colourful sheen of this film distract them from the truth – Querelle is not for the faint of heart, and is perhaps the best embodiment of exactly what an instigator against good taste Fassbinder was, and how he defined himself as someone perpetually in stern combat with the principles of proverbially “decent” filmmaking. Anyone venturing into this film needs to know exactly what to expect – the story of a lascivious sailor and his crew finding their way into the town of Brest, known for its loose morals and abundance of sexually-liberated individuals both sides of the identity spectrum, is not one that we could expect Fassbinder to approach with anything other than his trademark tendency to employ a deranged form of hypersexuality into many of his films – he’s not necessarily someone who abides by the belief that a story about sexuality needs to remain within those boundaries, but he rarely took on such stories without making use of all his resources in telling them. Much like Warhol, the director is not afraid to court controversy – and through the callous conversations (which are sometimes overly stilted and explicit, which gives Querelle the sensation of being only thinly-veiled pornography at times), and the presence of an array of actors employed primarily for their appearance, which Fassbinder has very little issue with objectifying to the point where this might as well have been a full-length advertisement for Tom of Finland, makes for viewing that may be uncomfortable far too often, but serves a significant purpose in its own right, being a daring and unflinchingly honest demonstration of the inner machinations of a society undergoing considerable change in the wake of a sexual revolution, which very few of them are able to endure without falling victim to the carnal, animalistic desires that seem to govern the lives of the occupants of this idyllic seaside town.

In this regard, Querelle is ultimately a litmus test, used to determine whether or not a viewer is able to separate the surface-level content with the more nuanced underlying message. The film doesn’t only work as a terrific piece of alternative queer cinema, where sexual fluidity and the desire for carnal satiation is prioritized over traditions (Fassbinder was notoriously allegiant to the idea of shattering preconceived notions of what is considered conventional, whether it be the romance between two people of different ethnicities, backgrounds, or between those who share similar traits, such as gender identity or sexual proclivity), but also as a parable for some broader issues. Making use of a diverse range of characters – some of them played by recognizable arthouse superstars like the beguiling Jeanne Moreau and the exceptionally-gifted Franco Nero – each one of them carrying with them a distinct fragment of the overall message that pulsates through the film, placing each one down as the film progresses, Fassbinder is able to provide a compelling glimpse into human existence through an exceptionally unique approach that strips away all sense of pretention, and instead replaces it with a wildly deranged, but beautifully poetic, story of desire, which transcends the boundaries of mere erotica (with the director proving once again to be someone who can traverse the very boundaries of decency without ever resorting to exploitation, despite the criticism he has received as someone who made shocking content simply for the sake of alienating sensitive viewers), demonstrating a satirical sense of humour, with larger-than-life personalities taking up the screen and leaving an indelible impression, and a heartfelt sense of seeking to understand the most visceral cravings we have as human beings, which contributes to a film that seems to be a misunderstood masterpiece, on the sheer virtue that it refuses to adhere to any known conventions.

Fassbinder may have been a filmmaker with a very distinct directorial vision that could be polarizing to viewers, but anyone who denies his brilliance may just not have been able to see beyond his intentions, considering how he is one of the rare instances of style superseding substance being an extraordinary asset for a filmmaker. It’s a peculiar and disconcerting voyage into the human condition that feels beautifully-composed, even when it is at its most haunting, with every moment being executed with precision and sincerity, perhaps more than we’d bargain for based on what we’re used to seeing from the director. Ultimately, Querelle is exactly what we’d expect based on a cursory glance – a sumptuous, darkly comical socio-cultural odyssey with a wide range of unforgettable characters (played by some truly memorable actors), and a story that transcends all morality in favour of a more subversive approach to the general principles of the art form which Fassbinder, a director whose constant desire to be as provocative as possible, made his very own. It may be his last film, but it doesn’t feel like a farewell in any way, rather working as the start of a new stage that we may not have seen directly from the director himself after his death, but which was picked up by the legions of young filmmakers that he inspired, whether through his laissez-faire approach to constructing films, or his earnest and undying commitment to going about these stories on his own terms. Quintessentially the product of a director with a clear vision, and unflinching in its dedication to being bold and striking, Querelle is perhaps more of a triumph than it had any right to be.