Luce is a film I truly don’t care for. No matter how much effort I put into revisiting this film, mainly since it has been hailed as some modern masterpiece, can convince me that it’s anything other than plainly mediocre, and the appeal surrounding it continues to evade me. Unfortunately, as much as I wanted to find some merit in this film, there really just anything there to begin with, so the experience of working my way through this film again, as part of yet another reevaluation (particularly in regards to one of the performers in general) yielded very little positive results. Julius Onah is a director who is putting himself on the cultural map, mainly through his attempts to establish himself in the industry with some minor but effective works (even his most high-profile film, The Cloverfield Paradox, has some merit to it) showing that he possesses a certain versatility as a filmmaker that makes him someone to watch. However, Luce is not the film that deserves to be his breakthrough moment into the realm of serious filmmakers. Instead, it’s nothing more than a misguided work of socially-charged commentary that is blandly adequate at best, hopelessly mediocre at work. By definition, Luce isn’t a bad film – it is neither ambitious enough, nor possesses any iota of the effort, to qualify it to be anything other than an uninspiring work that handles a narrative that goes in about a dozen different directions, without developing any of them beyond the most essential confines of what a film should be in form. If there’s any way to describe Luce, it would be as nothing more than a serviceable drama with overtures of psychological thriller, making for an unremarkable, muddled mess of a film that has captured audiences’ attention around the world, hence the immense heartbreak of realizing that, unfortunately, this film is simply just not all it’s cracked up to be, even when attempting to revisit it and find some merit in what is almost entirely just a vapid work of uninspiring cinema.

Luce is a film I truly don’t care for. No matter how much effort I put into revisiting this film, mainly since it has been hailed as some modern masterpiece, can convince me that it’s anything other than plainly mediocre, and the appeal surrounding it continues to evade me. Unfortunately, as much as I wanted to find some merit in this film, there really just anything there to begin with, so the experience of working my way through this film again, as part of yet another reevaluation (particularly in regards to one of the performers in general) yielded very little positive results. Julius Onah is a director who is putting himself on the cultural map, mainly through his attempts to establish himself in the industry with some minor but effective works (even his most high-profile film, The Cloverfield Paradox, has some merit to it) showing that he possesses a certain versatility as a filmmaker that makes him someone to watch. However, Luce is not the film that deserves to be his breakthrough moment into the realm of serious filmmakers. Instead, it’s nothing more than a misguided work of socially-charged commentary that is blandly adequate at best, hopelessly mediocre at work. By definition, Luce isn’t a bad film – it is neither ambitious enough, nor possesses any iota of the effort, to qualify it to be anything other than an uninspiring work that handles a narrative that goes in about a dozen different directions, without developing any of them beyond the most essential confines of what a film should be in form. If there’s any way to describe Luce, it would be as nothing more than a serviceable drama with overtures of psychological thriller, making for an unremarkable, muddled mess of a film that has captured audiences’ attention around the world, hence the immense heartbreak of realizing that, unfortunately, this film is simply just not all it’s cracked up to be, even when attempting to revisit it and find some merit in what is almost entirely just a vapid work of uninspiring cinema.

It is important to note that Luce has some good qualities – so we’ll start with those right from the top since there are certain aspects that spare the film from descending too far into its own self-indulgence to lose sight of the fact that it’s supposed to be telling something of a story. One of the few truly positive aspects of the film is its intention – Luce comes at a very important time in global history, where issues of race are deservedly in the spotlight, being given the attention they deserve, with debates, arguments and insightful discussions taking place to determine the way forward and change the collective thinking in some small way. Art has certainly reflected that, and Luce is a good example of this in practice, with its commentary on race relations being quite interesting at moments, creating the illusion that it’s reaching an effective conclusion that will make sense of everything. These are few and far between, but they’re certainly there, and lend this film some gravitas, even if only fleetingly as a way of showing that the film is fully aware of the issues it’s commenting on, which it addressed through directly looking at them. This creates a tension throughout this film that is certainly extremely effective, albeit only at certain points, where the central premise actually works to comment on the issues depicted around it, rather than simply passively residing next to a story that frequently seems to point out how smart it thinks itself to be – tension only makes an impression when there’s something for the viewer to grasp onto. This approach doesn’t work for even the most established filmmakers, so for Onah to base an entire film around since issues seem slightly misguided, and not even the tension that reaching the breaking point that is clearly within its wheelhouse.

Ultimately, this tension is used well when the director and his cast can understand the motivations around it – the problem is, a film like Luce doesn’t seem to have any clear reasoning for the story its telling, which creates something of a disconnect between the audience and the film, which would certainly be an effective tool had it been used correctly. The simmering anger that pervades throughout this film, particularly when covering the topic of race, is very effective and is where the film shines the most. The problem comes in how Onah truly believed that this story is able to stand on its own, where murky character motivations exist simply to add nuance to the figures depicted, and where an atmosphere of insidious dread justify this film as something that audiences should pay attention to. In the hands of a more skilled filmmaker, this may be convincing. Unfortunately, as much as I admire his audacity, Onah seems singularly unable to shepherd this film to any discernible and logical point – instead, numerous strands of narrative are thrown out, in the hopes that presenting these fragments of a variety of lives somehow add depth and nuance to characters that are nothing more than thinly-veiled archetypes, almost as if Onah and fellow screenwriter JC Lee who wrote the play from which this film was adapted, purchased a “colour-by-numbers” book on how to put together a derivative drama that hits all the familiar beats without saying anything insightful. There are many aspects of a film like this (particular when it comes to independent work, which is understandably difficult to put together) that are forgivable – but when the primordial fabric of this film is built not only from the disregard for logical narrative flow, but also the refusal to develop its characters or the story they’re placed in, there’s an enormous problem, and a perfect reason behind the uninspiring dullness this film seems to be thriving on, without realizing that its edginess is actually the result of misguided ineptitude to tell a convincing story.

Furthermore, another area in which Luce is lacking is in how the story is executed. Adapted from the play by JC Lee (who also wrote the screenplay alongside Onah), Luce is not the first time in which a stage production is brought to the screen. As a relatively simple piece of theatre, it was certainly not going to be difficult to translate to the screen – which is the logical line of thought, especially when a film like this is built mostly on the interactions between various characters. This film joins the elite company of play adaptations that not only seem to be singularly unable to grasp the very concept of what cinema is supposed to be but seem to be actively defying the most fundamental principles. Much like the process of adapting the source material, the director is following a set of guidelines that demonstrate exactly which overwrought cliches to use, and in which particular contexts, with every imaginable piece of predictable dialogue being put through the film at some point. In all honesty, Luce is an atrociously-written film, brimming with some of the most taut dialogue ever committed to film, and delivered in such a way that those speaking it seem to genuinely believe in what they’re saying. The film puts very little effort into translating this work to the screen, and even makes the major mistake of compounding nonsensical sequences that are not available on stage, such as the innumerable shots of the titular character walking, running or gliding towards the camera, as if this is to suggest some complexity or nuance when in actuality, it’s a cheap trick from a film that may have good intentions, but not good enough to put in all that much effort in the first place.

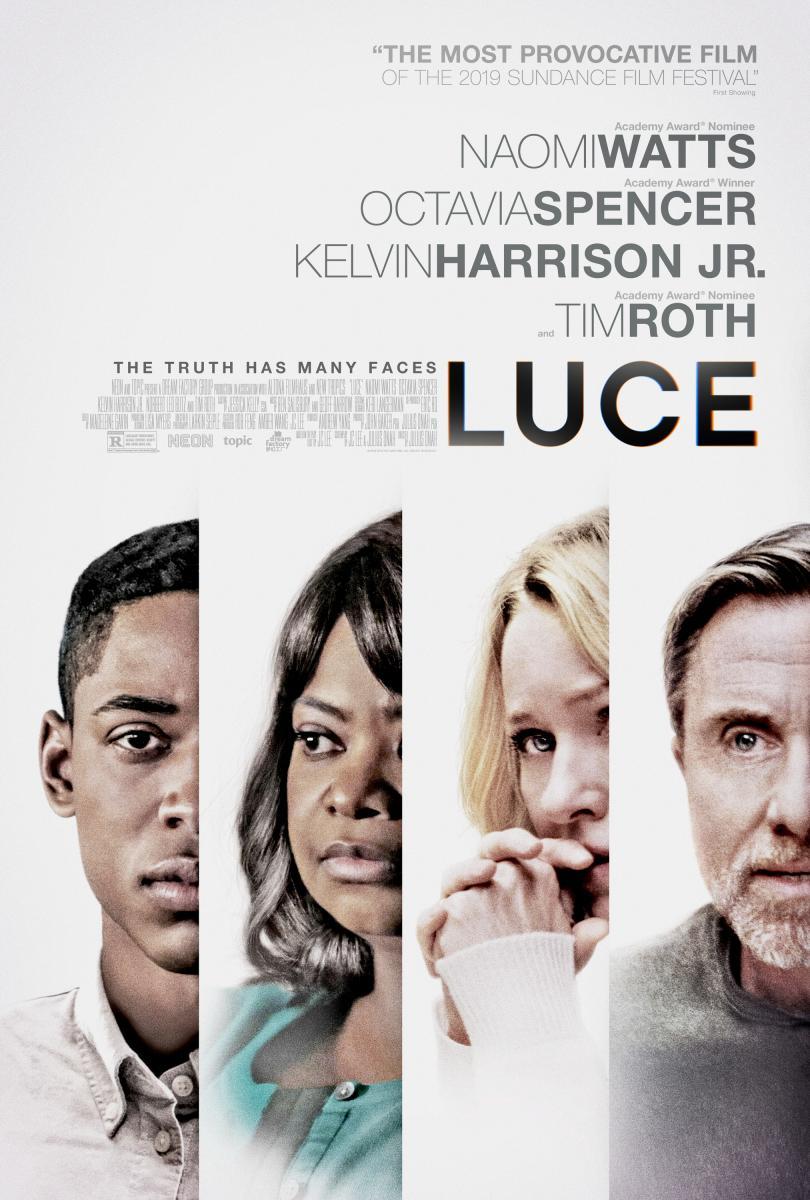

Much like every play-to-film adaptation, Luce depends on its actors to bolster it. Unfortunately, Kelvin Harrison, Jr. is not an actor that can convincingly play the titular role without coming across as truly unlikable, and not in the way the film suggests. Despite being the focal figure, the film does a relatively poor job of establishing him as the complex anti-hero we are supposed to believe him to be – right from the first moment, we’re presented with close-ups of Harrison as he trods through the hallways or runs down his suburban street, almost as if the film is trying to tell us to pay attention to a character we already know is the sinister embodiment of an angry generation looking for justice. Harrison definitely does have a future in the industry, but his work here is a few too many beats short of a star-making performance, and when coupled with his relatively recent arrival into the industry, the result is something that just doesn’t come together in any meaningful way. Watching a young man slowly become enveloped by evil is definitely a compelling subject – except when the representation of it is so bland and lifeless, the viewer naturally gravitates towards other people in the frame, which is not the kind of result you want from a film so clear in its intentions to make Harrison a star, it goes to any lengths to show him as the lead, without taking on the fundamental quality of actually giving him something meaningful to do. Naomi Watts and Tim Roth give the exact kind of performances you’d expect from them both and are decent in their parts, if not unremarkable. The star of the film is unquestionably Octavia Spencer, who is branching off from a series of majorly popular films that don’t give her much to do and is here occupying a fascinating role of a high school history teacher who becomes the victim of her own paranoia when students start to fight against her methods, not only of teaching but of being an educator. By the end of the film, I’m not sure if you’re supposed to hate Harriet or pity her, but considering what this film put Spencer through, I’m inclined towards the latter.

As much as there was something to be said with Luce, it just never finds its voice in any discernible way. There are so many different narrative threads, to the point where any logical viewer will take it as meaning the film is heading somewhere, only to have every bit of potential squandered by a final act that does an even bigger disservice to what could’ve been a very insightful film about cross-generational relationships and the role of race relations in contemporary America. This was what this film was going for, but unfortunately fails to deliver in any meaningful way. It is a film that features a limp storyline that fails to converge into anything that can be considered worthy of the overt moralizing this film seems to do, features lacklustre direction that does very little to elevate the atrocious script (who Onah and Lee managed to put every conceivable cliche into this film in terms of the dialogue is a feat in itself), and a set of performances that range from mediocre (in the case of Harrison) to perfectly fine but still extremely stilted and underwritten (in the case of Spencer). There’s really nothing special about Luce, a by-the-numbers independent drama that promises an enormous amount, and delivers on nearly none of it – I’ll reiterate that I don’t consider this a bad film, primarily because not only does it seem to have its heart in the right place (which is not an excuse for ineptitude but is something of a merit), but because it simply doesn’t have anything memorable enough for it to be remembered, one way or the other. Its the kind of film that genuinely believes itself to matter more than it actually does, and while there is a worthwhile message embedded somewhere in this film, it’s lost in a maelstrom of incompetent arrogance that makes for awfully bland viewing that tests the viewer’s patience, and makes us yearn for something with some semblance depth, which is certainly not what we get out of Luce, despite its bizarre belief that it is somehow an insightful portrait of modern society when it actuality, its a bundle of misguided ideas and underwritten situations that amount to very little that can be remembered if anything at all.

The premise of Luce is a challenge to determine who we believe, a teenage boy with striking good looks or a corpulent educator with a 15 year history of strong service. Screenwriters Julius Onah and J. C. Lee tell us in the film’s first shot the truth.

The film then becomes a challenge for the audience. Are we so moved by the story of a seven year old child, adopted from a war torn nation and raised by two loving professionals. who evolved into a star athlete and a valedictorian that we can deny an ever growing collection of evidence that this young man may be a sociopath? Are we as a culture so dismayed by an ever growing laundry list in the media of abusive, incompetent teachers that we no longer trust the word of a veteran educator? In today’s environment of a growing awareness of both declining school systems and unjust treatment of boys of color, this film forces us to examine our own prejudices.

In a key moment, young speech and debate student Luce addresses his school community at an assembly celebrating multiculturalism with a discussion of his personal experience. He speaks of how his white adopted mother was unable to pronounce his birth name so she and his adoptive father arbitrarily changed the boy’s name to Luce because it means light. Luce is a derivative of the name Lucious which is defined as light. Luce actually means a fully formed fish. There is a shared family tale recounted in the film of Luce’s early years living in America. The newly immigrated boy threw a fish across the room to see it fly. At the end of the film, Luce brings his adopted mother a new fish for a new beginning. The gesture is manipulative and meaningless. Luce is already fully formed. The last image of Luce running is unexplained. We are left to draw our own conclusions on the potential of this young man.

I found the narrative to be messy with too many red herrings. Having the teacher’s sister, fresh from a rehab program, show up at school in an emotional meltdown that results in her stripping to rant nude in front of the students until police arrive and subdue her with a taser seemed unnecessary and prurient. Of course, the students filming the episode on their cell phones and the school administration unsuccessfully attempting to collect all the recording devices felt true. Overall, this story of people struggling to do the right thing with issues of race, cultural competency, assimilation is intriguing. The film provokes both reflection and dialogue