The Joy Luck Club is composed of four elderly Chinese women who immigrated to the United States of America decades prior to knowing each other, having met at church and formed a strong bond over the years. They spend their afternoons playing mahjong and telling stories, normally about their past experiences. One of them, Suyuan (Kieu Chinh) has recently died, and her daughter, June (Ming-Na Wen) has become her de facto replacement in the group, on the insistence of the women she calls Aunt Lindo (Tsai Chin), Aunt Ying-Ying (France Nuyen) and Aunt An-Mei (Lisa Lu). They don’t bring her in only to be the fourth person at the table – each one of these women has a story to tell, particularly around their own origins, as well as their individual relationships with their daughters. Over the years, they have experienced considerable hardship – mental health issues, sexual and emotional abuse, poverty and a range of other challenges that characterized their early lives, but have taught them valuable life lessons that they intend to pass onto their own, American-born daughters, who seem to be oblivious to their own cultural roots. Over the course of one afternoon, at a party being thrown for June on the eve of her departure to China to be reunited with her long-lost sisters, each of the women – both mothers and daughters – reminisce about the past, evoking thoughts of the challenges they have faced to get where they are and know what they know now, as well as fondly remembering their difficult but worthwhile journeys to who they have become today. Their lives were not always easy, but they were certainly far from uninteresting, each one of them holding onto a special lesson than they hope will inform the younger generation to the boundless resilience of the human spirit, and the importance of holding onto even the most painful memories.

The Joy Luck Club is composed of four elderly Chinese women who immigrated to the United States of America decades prior to knowing each other, having met at church and formed a strong bond over the years. They spend their afternoons playing mahjong and telling stories, normally about their past experiences. One of them, Suyuan (Kieu Chinh) has recently died, and her daughter, June (Ming-Na Wen) has become her de facto replacement in the group, on the insistence of the women she calls Aunt Lindo (Tsai Chin), Aunt Ying-Ying (France Nuyen) and Aunt An-Mei (Lisa Lu). They don’t bring her in only to be the fourth person at the table – each one of these women has a story to tell, particularly around their own origins, as well as their individual relationships with their daughters. Over the years, they have experienced considerable hardship – mental health issues, sexual and emotional abuse, poverty and a range of other challenges that characterized their early lives, but have taught them valuable life lessons that they intend to pass onto their own, American-born daughters, who seem to be oblivious to their own cultural roots. Over the course of one afternoon, at a party being thrown for June on the eve of her departure to China to be reunited with her long-lost sisters, each of the women – both mothers and daughters – reminisce about the past, evoking thoughts of the challenges they have faced to get where they are and know what they know now, as well as fondly remembering their difficult but worthwhile journeys to who they have become today. Their lives were not always easy, but they were certainly far from uninteresting, each one of them holding onto a special lesson than they hope will inform the younger generation to the boundless resilience of the human spirit, and the importance of holding onto even the most painful memories.

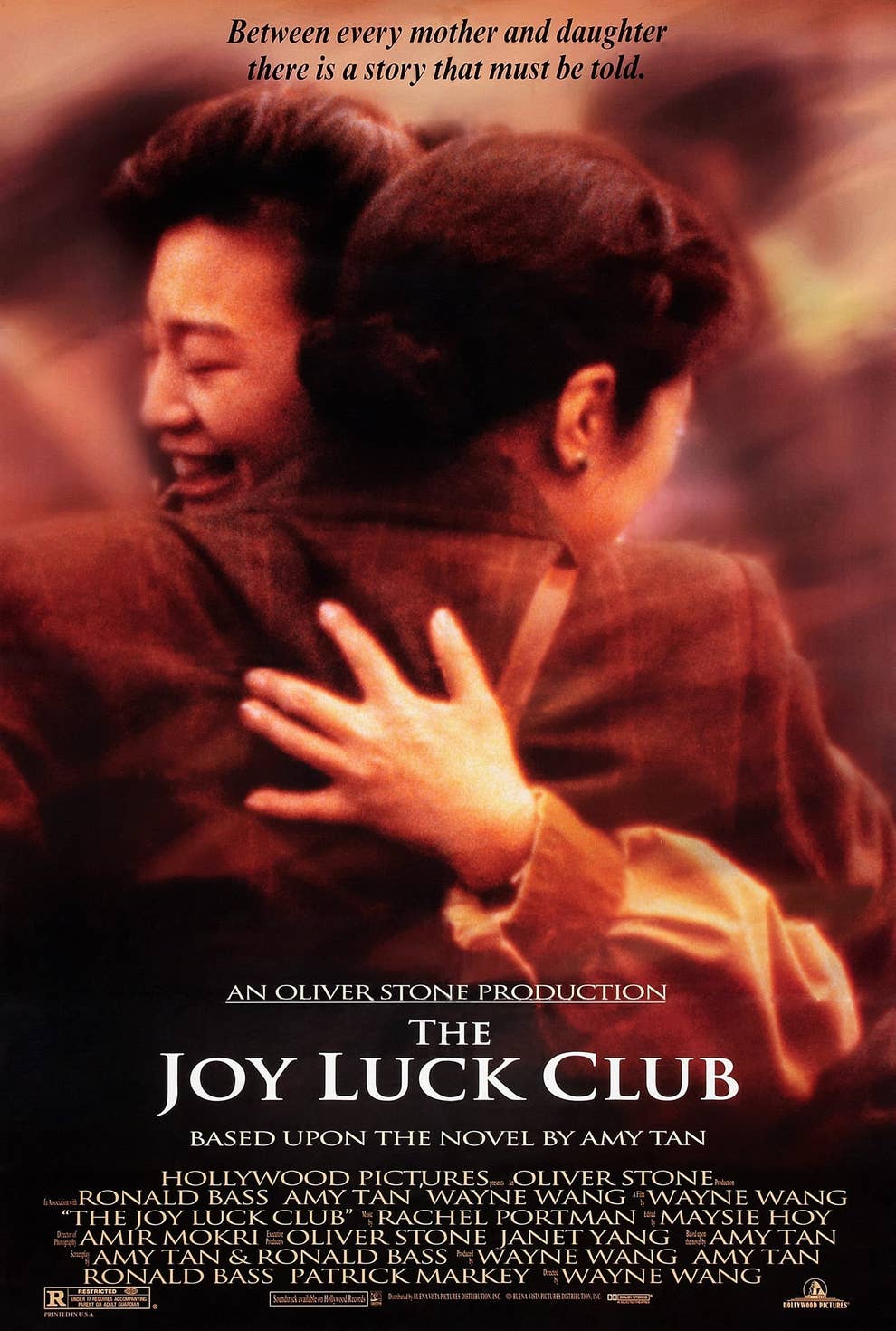

Representation matters, now more than ever. The Joy Luck Club was a revolutionary piece of filmmaking for many reasons – based on the widely acclaimed novel of the same title by Amy Tan, the adaptation by Wayne Wang was only the second theatrically-released film made about the Asian-American experience with a predominantly Asian cast (and to date, it is shockingly only the third one overall), and represented a seismic shift towards looking at an enormous group of individuals that had not always received the roles they truly deserved, often being relegated to memorable supporting roles that, even if not playing off harmful stereotypes, were always there to bolster someone else. The Joy Luck Club was the film that attempted to change this, and looking at it over a quarter of a century later, it becomes incredibly clear that this was not just another sentimental drama that tugged on the heartstrings and presented audiences with a sweet but forgettable story, but rather something far more profound, both in what it was and in what it intended to be. Tan’s novel was a cultural phenomenon, and the translation to the screen was nothing if not an admirable attempt to take this beautifully poetic story of cross-generational relationships and broadcast it to a much wider audience, introducing viewers to a new range of stories, and giving an astounding ensemble of actresses the opportunity to play the roles of a lifetime in one of the most pivotal films of the 1990s. The Joy Luck Club has lingered on the public consciousness enough to make a lasting imprint, but its importance has somewhat unfortunately subsided, which means that there are whole generations of viewers that haven’t been introduced to this glorious story that is waiting anxiously to move audiences in the most unexpected ways imaginable and remind us of the incredible power of a story well told.

The Joy Luck Club assembles a cast of some truly gifted performers across numerous generations, casting nearly a dozen Asian actresses in the roles of the Joy Luck Club, their daughters and a variety of peripheral characters that weave throughout the story, making this one of the most extraordinary ensembles in film history, a statement that can be made without even an iota of hyperbole. American films often struggled to portray Asian characters as anything other than the archetypal “dragon lady”, or as exotic objects of desire. The Joy Luck Club presents us with eight characters in which these hackneyed traits are mercifully lacking – each one of them has a distinct personality, inspired by individual stories that the film explores in beautiful detail. This leads to a set of performances that run the gamut of emotions, creating an unquestionably potent set of characters that the actresses bring to life with such immense gusto. Its singularly impossible to choose a favourite – the older generation are all wonderful, with Kieu Chinh, Tsai Chin, France Nuyen and Lisa Lu confirming their status as cinematic icons with these wonderfully exuberant performances that also carry a heft that is often missing from these scene-stealing supporting parts. Ming-Na Wen (in the role that could be considered the closest to a leading part), Tamlyn Tomita, Lauren Tom and Rosalind Chao are wonderful as their daughters, toggling the line between two cultures with such sincerity. The Joy Luck Club possesses the rare quality of being one of the few ensemble films without a single standout – everyone is absolutely astonishing, delivering complex, layered performances. Whether coming from the hardworking veterans who had seen every side of the industry, or the audacious newcomers who were hoping to make their mark in an industry that had often been inadvertently hostile to them, the cast of this film is truly exquisite, and the story rests firmly on their very capable shoulders, as they venture into the depths of this fascinating characters and extract every bit of potential.

One of the aspects that has made The Joy Luck Club such an enduring piece of cinema is how it is primarily a film about cross-generational relationships. There have been numerous films that have focused squarely on the differences between generations, but few of them are as impactful as this one. Whether its the result of Tan writing from a place of having been aware of the content she was portraying, or the work of a group of artists working in collaboration with Tan to translate her novel to the screen, there’s a certain familiarity that even those completely separate from the cultural context of this story will be able to find some element to latch onto, allowing it to flourish into a gorgeous tale of resilience. The key to this film is its approach to memory – composed of a series of interweaving vignettes, The Joy Luck Club makes use of flashbacks to revisit the past, narrating the stories of these eight women and their intertwining relationships. Not necessarily an anthology film of memory (as some have implied it to be), but rather a complex story of various segments of the past intersecting in portraying a story of differing identities across decades, cultures and even continents, Wang and Tan work in careful collaboration to create something truly meaningful, focusing on the trials and tribulations of its protagonists, giving us insights into their lives and the formative moments that went into constructing them as the fiercely independent, but deeply complex women that have accomplished wonderful achievements but carry the burden of their pasts, which are explored with a precision and elegance, which is exactly what this material deserved. Anything even marginally less respectful, such as an attempt to trivialize these experiences, would have resulted in a film that may have been lighter, but at the expense of some of the most heart-wrenchingly beautiful storytelling ever committed to film. The film pays tribute to this story in astonishing ways and avoids becoming overwrought, even at its most emotionally-devastating.

The Joy Luck Club is a film that takes quite an impressive approach to its story – it may situate us in a small apartment in San Francisco at the outset, but it soon becomes clear that this is a film that is going to span much further. Tan’s story is an enormous epic condensed into a very intimate story of the relationship between mothers and daughters, where both sides of the tale are represented with immense earnestness, never being content to rest on its laurels as a moving social drama, but still being ambitious enough to go further than many filmmakers would dare to go with this material. The film presents us with many different periods across the characters’ homeland of China, and their eventual new lives in the United States, with each story taking place in a different location and giving insights into the origins of one of these characters, and Wang commits himself to representing each one of these vignettes with the authenticity required to evoke every bit of emotion from it. On a purely creative level, The Joy Luck Club is incredible – how the director manages to oscillate between past and present without much need for exposition (the inclusion of a wraparound story and the narration assisted massively in contextualizing some of the nuances that are often lost in the transition between page and screen), and create a film of this scope from the relatively paltry material he was offered was an achievement on its own, and it remains bewildering that this didn’t serve as the launching pad for Wang as one of his generations most exciting voices. The Joy Luck Club is an astonishingly beautiful film in both scope and intention, with the subtle intricacies of the story being channelled through a potent approach to representing the shifting narrative without losing any of the momentum it builds throughout. This is a film that took many risks, and it was rewarded handsomely for its intrepidity by becoming one of the period’s most astounding social dramas, and like many of the great films about memory that preceded it, it keeps everything at a relatively simple level, while consistently hinting at something much deeper.

We can wax rhapsodic about how important The Joy Luck Club is, and how it was a watershed moment of representation, or how the cast is astonishing and the filmmaking immaculate. However, the reason why this film has pervaded the culture as much as it has is not only because of what the film says but also what it stands for. This is not an insular story about the Asian-American experience or the challenges faced by immigrants. They play a major role, but they don’t define the film – rather, it is the more metaphysical intentions that make The Joy Luck Club so special. This is ultimately a film about family, particularly the relationship between mothers and their offspring, and how time brings many experiences, and whether positive or negative, they’re part and parcel of who we are. We grow up, and we grow apart, but we’re always intertwined with each other, based on both our own personal experiences and the ancestral experiences that lead us to this very moment. The film seems to carry a message of not only resilience when faced with obstacles, and a motivating manifesto to remember that no challenge is insurmountable, but also one of profound unity. There is certainly not any shortage of conflict in this film, with many of the stories often being built on these moments of competitive hostility – as June says towards the beginning of the film “Aunt Lindo was my mother’s best friend and arch-enemy”, which is not simply an amusing contradiction, but the very core of this film, and what makes it so effective because this is not an innocuous drama about unconditional unity, but also the challenge of overcoming the challenges when they’re posed by the people often closest to you. There’s a message in this film for absolutely every viewer, and it would be unprecedented for anyone to watch this film and not extract some piece of wisdom from this sweeping story told in a very simple and undeniably effective manner.

The Joy Luck Club is a truly beautiful film for a number of reasons, meaning something different for every viewer, but what spoke the most to me is how it approaches serious issues, not with gauche oversentimentality, but with earnest sincerity and honesty. This is an achingly beautiful film that is propelled on its emotional honesty, and there isn’t a single moment in which it appears to be manipulative or inauthentic in any way – rather, its a challenging work about cross-generational relationships that carries a warmth that every viewer, regardless of background, can openly embrace. The Joy Luck Club is a film that was clearly made with love – Tan delicately translates her wildly popular cultural phenomenon of a novel to the screen, and with the assistance of Wang, who proves himself to be driven by the same dedication to telling this gorgeous story, she manages to create one of the most achingly beautiful dramas of the 1990s. Filled with some of the most impressive performances of the period, on behalf of a cast of truly exceptional actors, the film conveys a deeply moving message with elegance, sentimentality and a great deal of humour. The Joy Luck Club is a bittersweet journey into the lives of a community that has rarely been given this kind of exposure, with its sensitive but steadfast approach to both relaying their melancholy experiences, and celebrating their extraordinary lives, making for a thoroughly moving story that resonates with every viewer. Wang and Tan put together a charming film that packages decades of potent commentary into an intimate collection of beautiful stories. The film will move you to tears, evoke endless laughter and perhaps be a poignant reminder to appreciate everything you encounter, because you never realize how useful even the most inconsequential moments tend to be until they’re nothing but the most distant memories.