Everything that can be said about Midnight Cowboy has already been said – it’s hailed as a classic, a film that helped usher in a new era of cinema, a groundbreaking social masterpiece that challenges heteronormative conventions and gave audiences at the time a chance to view and entirely different kind of story, one gloriously liberated from was almost universally considered sacred filmmaking. Therefore, the best approach to looking at this iconic film isn’t to try and add to the endless theoretical pieces about what it means, but rather to offer my own personal interpretation of it. I first saw Midnight Cowboy when I was much younger than I should have been to experience this film, which turned out to be one of the formative moments in my early artistic explorations – suddenly, the polished, perfectly-calibrated blockbusters and family-friendly fare were replaced by a gritty, heartwrenching tale of loneliness, and the strength of a very peculiar friendship in situations where optimism is rarely found. It was a film that captivated me and truly allowed me to see another side of storytelling, one that didn’t necessarily have to abide by any rules so much as it sought to actively break them. Revisiting this film recently, I was beyond pleased to find that it is just as gripping as it was over a decade ago, engrossing me in its subversive story about two men isolated by their social standing, united by their shared disdain for conventions, leaving me just as shattered as I was before. Midnight Cowboy is a truly beautiful film, a towering work of uncompromising fragility, delivered by a coterie of artists, working together to engage with material that is both controversial and deeply moving, resulting in one of the most profound films ever made.

Everything that can be said about Midnight Cowboy has already been said – it’s hailed as a classic, a film that helped usher in a new era of cinema, a groundbreaking social masterpiece that challenges heteronormative conventions and gave audiences at the time a chance to view and entirely different kind of story, one gloriously liberated from was almost universally considered sacred filmmaking. Therefore, the best approach to looking at this iconic film isn’t to try and add to the endless theoretical pieces about what it means, but rather to offer my own personal interpretation of it. I first saw Midnight Cowboy when I was much younger than I should have been to experience this film, which turned out to be one of the formative moments in my early artistic explorations – suddenly, the polished, perfectly-calibrated blockbusters and family-friendly fare were replaced by a gritty, heartwrenching tale of loneliness, and the strength of a very peculiar friendship in situations where optimism is rarely found. It was a film that captivated me and truly allowed me to see another side of storytelling, one that didn’t necessarily have to abide by any rules so much as it sought to actively break them. Revisiting this film recently, I was beyond pleased to find that it is just as gripping as it was over a decade ago, engrossing me in its subversive story about two men isolated by their social standing, united by their shared disdain for conventions, leaving me just as shattered as I was before. Midnight Cowboy is a truly beautiful film, a towering work of uncompromising fragility, delivered by a coterie of artists, working together to engage with material that is both controversial and deeply moving, resulting in one of the most profound films ever made.

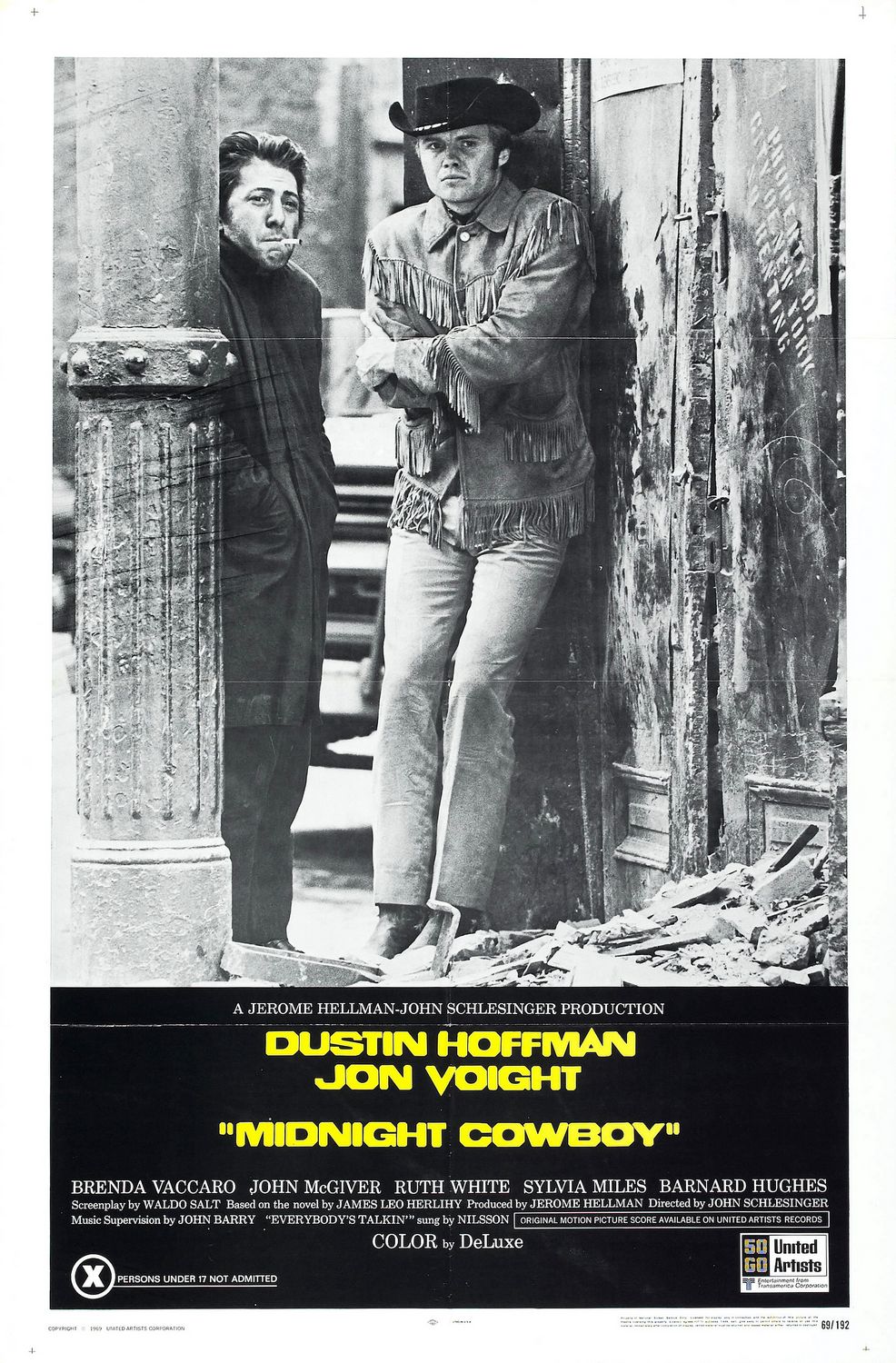

Half a century since its original release, Midnight Cowboy still manages to be as provocative and enticing as it was and certainly does not deviate from its reputation as one of the most challenging films produced during an era when such themes were not commonplace, at least not from the perspective of mainstream cinema. Naturally, we’re looking at the film from a modern viewpoint, with time having eroded a great deal of what made Midnight Cowboy so shocking in the first place – its status as some perverse, morally-corrupt tale of sordid activities and unethical behaviour has mercifully become outdated, with what remains being the raw portrayal of the human condition that John Schlesinger sought to demonstrate, taking on certain themes that would recur throughout his career, with the director bringing his experience in the kitchen-sink realism movement of his native Britain across the pond, situating us within the cross-country journey of one man not only seeking a new life but a sense of belonging, which he never quite experienced in his native Texas. It doesn’t take long for him to become acclimated to the New York rhythm, with the assistance of a particularly disreputable con-man being pivotal to his growth, and his realization that it isn’t where you find yourself that directs you towards the future, but rather how you use your environment – you can either become enveloped in the rapid pace of everyday life and lose sight of your own individuality, or you can dare to stand out – it’s not a mistake that the two most iconic images to come out of Midnight Cowboy are those of Joe Buck walking through a crowd, his cheerful, Stetson-clad demeanour contrasting heavily with the shivering, dour New Yorkers, and the other being Joe and Enrico “Ratso” Rizzo, two of the most seemingly-incompatible figures imaginable, walking down the same streets, surrounded by unfamiliar faces, isolated by the crippling despair they share, in search of some salvation, willing to take absolutely anything they can get, even if it means sacrificing what morals remain.

Venturing into the core of Midnight Cowboy and its powerful social message is both an intimidating, but thoroughly engrossing, endeavour, especially when we look at it from a more modern perspective, where material that was previously improper has slowly been repurposed as being more honest in its intentions than unseemly in its execution – perhaps a bizarre concept from a contemporary standpoint, especially considering the leaps and bounds cinema has taken in terms of representation, a film that not only prioritizes a pair of character of seemingly-ambiguous morals in the central roles but also doesn’t feel compelled to have them pay the consequences of what is essentially nothing but their own choices, was revolutionary. This intense approach, where the more bleak subject matter is used less as a crutch for a morality tale, but more as the impetus for a powerful investigation into more metaphysical concepts, sets Midnight Cowboy apart from many other films produced at this era, mainly because Schlesinger is not afraid to express the truth – the shame and disrepute that would inevitably be asserted onto this film was perhaps the most beneficial aspect, because while it doesn’t deserve such derision, especially considering how tame this supposedly sordid material actually way, but rather incited interest in a film that is built less from the general story, and more from the specific themes it seeks out to explore. Controversy is rarely ever negative when it comes to the longevity of a film, which is precisely why Midnight Cowboy continues to be discovered and celebrated by diverse audiences, who are now offered the opportunity to look at this film with a contemporary sensibility, where the ludicrous censorship and protests of indecency are almost entirely irrelevant, with only the stark, poignant themes being subjected to the admiration of audiences more willing to embrace this film and the meaningful message it conveys.

At the heart of Midnight Cowboy are two incredible performances by a pair of actors who may not have had their careers defined by this film, but certainly used it as a platform to elevate the work they would go on to do. Jon Voight and Dustin Hoffman are so intertwined throughout the film, its often difficult to choose which one stands out more, especially because of how Schlesinger brings out the polarity in the two characters, exposing their differences less as a way of introducing another of the worn-out “odd couple” trope, and more as a means of creating a visceral portrait of a city that is seemingly unforgiving to those on the outskirts. The titular cowboy is played by Voight, whose wide-eyed enthusiasm slowly erodes, but never completely disappears, especially in how he characterizes a figure like Joe Buck, who could’ve so easily been just another archetype. In Voight’s incredibly capable hands, Joe becomes one of cinema’s most compelling protagonists, most particularly in how his growth is so clear, yet executed with such nuance, we barely even notice the gradual change, which manifests in his metamorphosis from a free-wheeling Texan cowboy with enormous aspirations to a bitter New York hustler, jaded from the false promises he’s been given by those who take advantage of his ignorance as an outsider. Whether it’s in his hat tilting further back, or his beautifully-detailed shirts becoming grimier and slowly becoming unbuttoned, Joe abandons his upright morals as a result of becoming a part of a city where survival supersedes ethics. Dustin Hoffman stands in stark contrast, playing the meek Ratso Rizzo, who overcomes his disability and unfortunate social situation by a scrappy disposition that sees him going to any lengths to make a living, even if it means resorting to outright criminal behaviour. Hoffman was not only a terrific movie star, but a compelling character actor who took on roles like this, categorically against the type many of his contemporaries would and ultimately giving a memorable performance that is often incredibly funny, but also deeply heartbreaking, especially when the film starts to pay attention to Rizzo as a character, rather than just a plot device.

The performances of Voight and Hoffman are imperative to the success of the film, as Midnight Cowboy is certainly not a film that could have thrived without their incredible work, especially since the core of the film is to do with their characters and their relationship. The film is mostly a character-driven piece that relies on interactions, whether with each other or with the wealth of supporting players who appear for only a single scene throughout the film (the effervescent Sylvia Miles being a particular standout) – and its the companionship between Joe and Rizzo that propels the film forward and allows it to delve deep into the psychology of these characters. The film focuses mostly on their friendship, but in a way where their individual traits don’t become intertwined in the same way their outward characteristics do – Schlesinger overcomes the challenge of giving these characters depth without distracting from the story or providing too much exposition by employing a series of flashbacks and fantasies, where the wounds of the past intersect with the hopes for the future, developing these characters in the most simple but effective way possible. It gives Midnight Cowboy a great deal of depth and allows it to comment on the insatiable loneliness of these two characters as they make their way through a hostile city, feeling the isolation that threatens to dismantle their fragile mental states entirely – and whether seen through the eyes of a hopeful dreamer, or a bitter realist that has been exposed to the truths of society, the commentary made through this affecting tale of an unconventional friendship is truly something to behold.

Midnight Cowboy is an achingly beautiful film – told with the sincerity of a filmmaker fully in command of his craft, but being willing enough to surrender himself to a story that may slightly deviate from his previous work, and beautifully interpreted by incredible performances by Dustin Hoffman and Jon Voight, this film is a resounding tale of overcoming circumstances and seeing the hope in even the most dire of situations. The film very often may tread through challenging territory – there are innumerable moments of unhinged, harrowing despair, particularly in the two main characters’ desperate struggle to survive – but there are also many moments when it becomes clear that Schlesinger was approaching this material less from the perspective of evoking a downbeat, sombre atmosphere, but rather constructing a poignant tale of a pair of friends sticking together, regardless of the challenges they encounter in their daily lives, which may be unconventional (and perhaps quite criminal), but it worth just as much as the apparently upstanding individuals that they become embroiled in. By the end of Midnight Cowboy, we have almost completely forgotten the film is about the trials and tribulations of a doe-eyed male prostitute and his disreputable best friend who will abandon all semblance of morality for the sake of a quick buck because what this film does well, above everything else, is piece together an ode to friendship – this is why the most meaningful moments of the film come when the relationship between the two leads is explored, separated from their schemes, developing into an ambitious, but deeply heartfelt, portrayal of the love that exists between two people compelled to work together simply to survive. Midnight Cowboy stands as one of the most extraordinary films of the New Hollywood movement, a quietly intense character-study that is both witty and heartbreaking. It’s honest, raw and sentimental without being manipulative. There are certain flaws that persist throughout the film, and while the controversy of the subject matter may be relatively inconsequential now, the specifics of how it treats the story can definitely be provoked. However, the intentions of this film were certainly earnest enough to make it a powerful cultural statement, and when the iconic opening bars of “Everybody’s Talking” by Harry Nilsson that bookend the film start, everything else just fades away into the disquieting euphoria of experiencing John Schlesinger’s incredible social odyssey, which evokes the delicate beauty of life and the unpredictable nature of existence. This is a film that means a lot to many people, not only for its artistic resonance, but its focus on identity and individuality, important concepts that are always omnipotent in art, but rarely with this kind of outward sincerity that truly warrants labelling Midnight Cowboy as a masterpiece.

Midnight Cowboy became the first and only X rated film to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. The victory was a landmark as the first formal acknowledgement of New Hollywood and an embrace of adult topics. The decision to choose this film was a powerful one. The cowboy remains an iconic symbol of American cinema. In 1969, a plethora of movie studios presented quite different variations on the image of the lone man in leather and denim.

Paint Your Wagon left viewers with the unsavory memory of cowboy Clint East-wood(en) meandering through rural northern Oregon and singing of how he talks to the trees of his dreams of love.

In contrast Sam Peckinpah offered a revisionist Western, The Wild Bunch, featuring popular but aging movie cowboys (William Holden, Ernest Borgnine and Ben Johnson) as an outlaw gang trying to survive in the modern world of 1913.

Superstars Paul Newman and Robert Redford made hearts flutter in the number one box office hit of 1969, an engaging comedic tale of two thieving cowboys, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.

The fifth Western that caught the public’s eye was True Grit, noted for its well received performance of America’s number one movie cowboy John Wayne as tough US Marshall Rooster Cogburn. Wayne would win a long overdue Oscar as Best Actor for his performance. He also rose eyebrows with his disdain for Midnight Cowboy. In a widely quoted interview, Wayne dismissed the Best Picture winner as “a story about two fags.”

In its initial release audiences widely accepted and acknowledged the love affair between two rather incompetent hustlers, the transplanted Texan Joe Buck (Jon Voight) and the ailing New Yorker Enrico Rizzo (Dustin Hoffman). I am perplexed to see how what so easily embraced fifty years ago is a topic now carefully avoided in contemporary discussion of the film. Because the movie has no formal spoken declaration of homosexuality, the issue isn’t or perhaps can’t be discussed today.

Personally I defy anyone to watch that final sequence on the Miami bound bus and not be moved by the tender care Joe offers to Rico. When Rico becomes incontinent, Joe doesn’t leap up from their shared seat. Rather, he wraps a comforting arm around Rico and cajoles him into a laugh. That final shot through the bus window as Joe lovingly embraces his friend as the long desired but elusive palm trees are reflected in the glass is heartbreaking in its beauty and celebration of love. I contend that audiences made Midnight Cowboy a top five box office hit in 1969, long before it won Best Picture, because of that tangible deep love.

The emotion was just as powerful to American filmgoers as we saw when another cowboy Ennis Del Mar climbing the stairs to Jack Twist’s boyhood bedroom and tightly clutched Jack’s workshirt to take a deep breath of the lingering odor held in the demin. An honest expression of love set to a haunting theme is what we all communally and expectantly gather in the dark and yearn to see. The movies ensure that the intimacy shared between Joe Bock and Enrico Rizzo will endure. And we will return again and again to celebrate it.