The Irishman is not just a gangster film. It’s an intricate cultural epic that functions as a darkly comical meditation on crime, ageing, the role of masculinity throughout the twentieth century and ultimately, death, both that of inflicting and experiencing it. Martin Scorsese presents us with perhaps his finest film in decades, a work of unparalleled scope and audacity that sees the legendary filmmaker at his most mature, crafting a brilliant piece that feels both complex and effortlessly coherent, one that is imbued with equal shades of unhinged violence in its depiction of the trials and tribulations of a particularly notorious individual and the various people who wove through his career as he rose to the ranks as an infamous figure, as well as a sense of insatiable melancholy, an emotional undercurrent often missing from films in this genre. This is a film where one’s mortality itself is called into question, pondered with such ease by a director whose work here continues to show that while he may have substantially grown as an artist over the years, changing his style and experimenting with different aspects of the cinematic form, there’s absolutely no one that can deliver a crime film like Martin Scorsese. This is not Goodfellas or Taxi Driver in terms of how it looks at criminal behaviour, but rather something far more profound and sinuous, a film that may not overtake some of his classic films in strength, but stands alongside them in showing that his talents have not eroded when it comes to the genre that made him such a distinctive and respected artist in the first place. In no uncertain terms, The Irishman is one of the most extraordinary pieces of American filmmaking produced this decade, and ultimately (and I say this without any sense of hyperbole), quite possibly as close to a perfect film as we’re going to get this year, which is really saying something considering the work Scorsese has done in the past.

The Irishman is not just a gangster film. It’s an intricate cultural epic that functions as a darkly comical meditation on crime, ageing, the role of masculinity throughout the twentieth century and ultimately, death, both that of inflicting and experiencing it. Martin Scorsese presents us with perhaps his finest film in decades, a work of unparalleled scope and audacity that sees the legendary filmmaker at his most mature, crafting a brilliant piece that feels both complex and effortlessly coherent, one that is imbued with equal shades of unhinged violence in its depiction of the trials and tribulations of a particularly notorious individual and the various people who wove through his career as he rose to the ranks as an infamous figure, as well as a sense of insatiable melancholy, an emotional undercurrent often missing from films in this genre. This is a film where one’s mortality itself is called into question, pondered with such ease by a director whose work here continues to show that while he may have substantially grown as an artist over the years, changing his style and experimenting with different aspects of the cinematic form, there’s absolutely no one that can deliver a crime film like Martin Scorsese. This is not Goodfellas or Taxi Driver in terms of how it looks at criminal behaviour, but rather something far more profound and sinuous, a film that may not overtake some of his classic films in strength, but stands alongside them in showing that his talents have not eroded when it comes to the genre that made him such a distinctive and respected artist in the first place. In no uncertain terms, The Irishman is one of the most extraordinary pieces of American filmmaking produced this decade, and ultimately (and I say this without any sense of hyperbole), quite possibly as close to a perfect film as we’re going to get this year, which is really saying something considering the work Scorsese has done in the past.

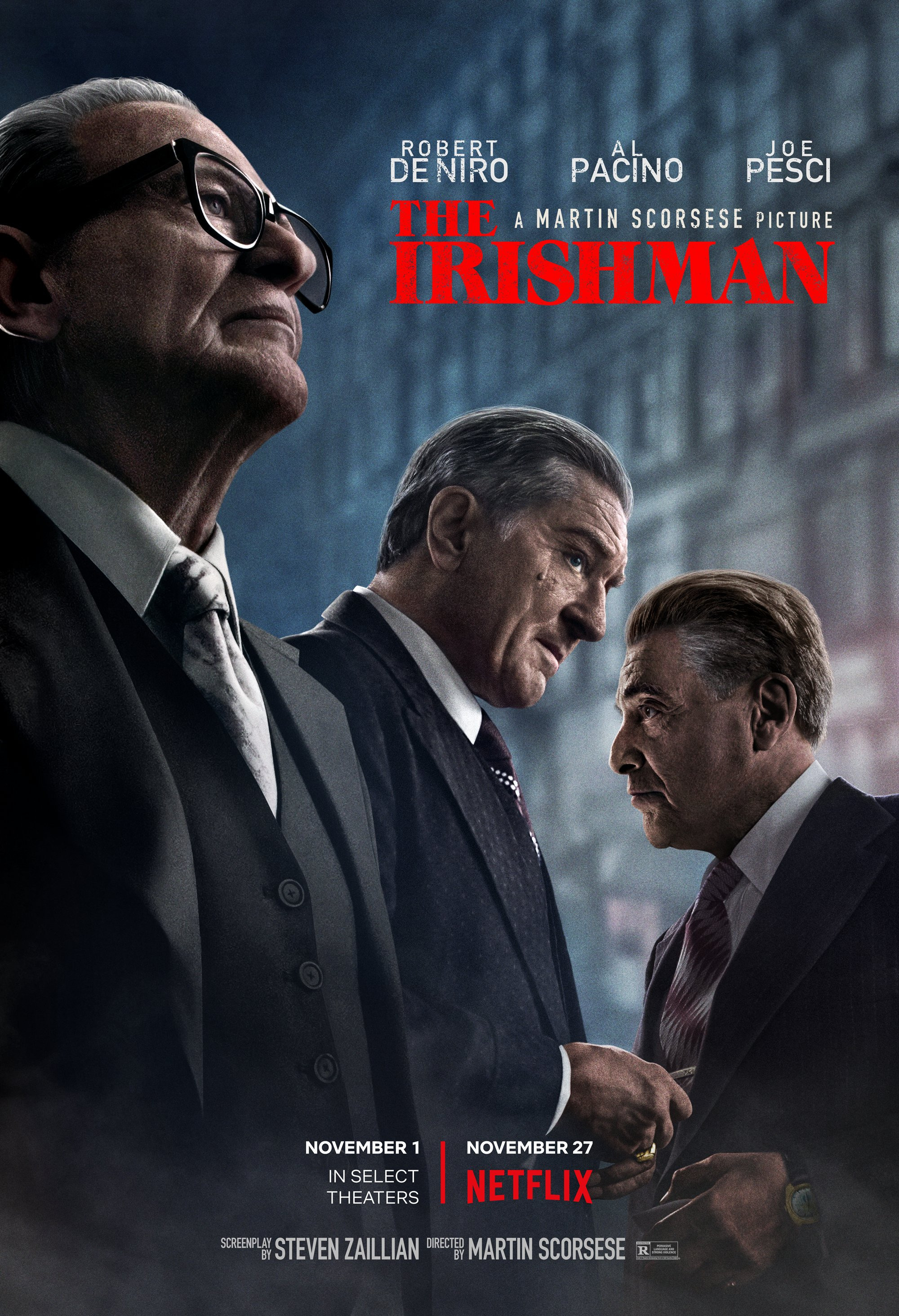

Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro) is a truck driver who soon finds himself entering into a new profession after being fired for some crooked dealings – painting houses. The only difference is, he deals in only one shade of paint: red. He begins working for Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci), a notorious mobster who takes a liking to Sheeran, who manages to slowly rise through the ranks of the criminal world through his dedication to the people he works for, the pride he takes in his work, and more than anything else, his commitment to go to any lengths to help those he is loyal to. This puts him in contact with Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino), the infamous trade union figure who headed the Brotherhood of Teamsters, the exact organization Frank was a member of before becoming an elite heavy for some of the nation’s most notorious gangsters. Hoffa is a very powerful man, and Frank is very good at what he does – the two work out a relationship that benefits both of them, which affords Hoffa complete safety, and Frank the power that comes with being a confidante to arguably the most influential man in the country, other than the president. Over the course of a few decades, we follow Frank from his position as a lowly labourer who secretly steals the stock of the companies he works for, to someone respected and feared by many people, mainly because of his influence on both sides of a cultural institution most Americans didn’t even know existed. Along the way, we see Frank ruminating on his past, framed by a few pivotal events that defined him as an individual, and showed his gradual rise to the top, and the inevitable decline that comes when someone is given far more power than they realize they can handle. The inner state of the protagonist is equally as important to the actual events he was involved in, whether directly or simply by proxy, and we follow him as he looks back at his life, showing that there is far more to this particular industry than most realize, for better or for worse, and that it is a truly perilous world that entraps anyone who gets too close.

The Irishman is an intimate, character-driven drama masquerading as an epic crime thriller, which is one of a few aspects of the film that doesn’t get mentioned all that much, especially when the spectacle of seeing Scorsese reuniting with some of his greatest collaborators (as well as working with one of the greatest actors of his generation for the very first time). What makes this film so surprising is how different it is from what we normally see from Scorsese, and how it shows the director taking on a very different kind of authorial voice than we’d expect. Perhaps not in terms of genre – he’s certainly been open to trying different conventions, and has taken many successful forays into different kinds of films, which makes this return to the gangster genre one that is both exciting and bittersweet, because it is clear he’s telling this story from a much older, more weary perspective, one that wasn’t particularly present when he explored similar themes in previous decades, where his youthful desire to explore excess and deviance in his own recklessly brilliant way made him a director who exploded into the industry. Rather, there’s an underlying sentimentality that we rarely see from him in terms of looking at some very grim themes, as well as a sense of humour that serves the film exceptionally well, especially in how it approaches some of the more absurd elements of the story, taken from the true crime book by Charles Brandt, which is the rare kind of biographical book that doesn’t dwell on conveying sordid details so much as it attempts to be an in-depth mediation on criminality and the role of morality in a profession that seems to entirely lack it. It is a sedate, carefully-constructed film, but one that is extremely volcanic at the core, constantly on the precipice of erupting.

Scorsese isn’t so much concerned with the truth as he is with the internal quandaries of these characters – hence why the film presents us with a pivotal scene in which we see the murder of Jimmy Hoffa, an event that many suspect transpired in this way, but ultimately is just the work of pure speculation. The Irishman is a film far more intent on exploring the inner depths of the characters, particularly those played by the three main actors, all of which give career-best work in what can only be described as a flawless symbiosis between a quartet of individuals working together to craft what is unquestionably a powerful manifesto on some themes far deeper than just those presented on the surface level. What this film does that sets it apart from what we’ve come to expect from a crime film made by Scorsese is that it shifts the discourse away from the traditional view of the gangster business, one normally portrayed as being brimming with debauchery and excess, and demonstrates it as a sordid industry that does have some glamour underlying it, which is only afforded to those at the very top. The Irishman is remarkably bare in how it approaches this story – the exuberant luxury of organized crime is used in a way that incriminates it more than anything else, showing it in an artificial light that exposes how truly insincere it is. This approach manifests in how detailed each element of the film is – just consider the final act of this film, which focuses on the downfall of Frank Sheeran and the people he worked for, and the heartbreaking scene where an aged Sheeran and Bufalino sit in the prison canteen, eating cheap bread and dipping it in grape juice, a far cry from the imported pane and expensive wine they shared at the beginning of their decades-long friendship. The Irishman is simply brimming with meaning, and the allegory and meticulous detail all amount to a truly enriching experience that keeps this film both a buoyant, enthraling crime epic, and a meaningful, deeply-intimate character study that gives us insight into a notorious gangster saga in sometimes unexpectedly beautiful ways, especially in its portrayal of the individuals at the core of it, who serve as our guides through this sometimes convoluted business.

In bringing these characters to life, Scorsese doesn’t avoid going after the very best performers, which resulted in the long-anticipated reunion between the director and arguably his greatest collaborator, Robert De Niro. This pairing has come a long way, and has resulted in some of the most distinctive moments of both careers. It is difficult to imagine Scorsese without De Niro, especially considering how truly historical the actor’s iconic entrance in Mean Streets, set to the resounding chords of “Jumpin’ Jack Flash”, where his youthful playfulness created an indelible impression that not only established him as a star, but cemented Scorsese as a director who would bring out the very best in his actors – who would’ve thought nearly half a century later, they’d make a film that not only looks at the real-life story behind De Niro’s character, but is also a strangely sentimental retrospective of the duo bringing this story to life, drawing from their own experiences growing older in an industry that rapidly changed around them. De Niro gives his best work in two decades in The Irishman – playing Sheeran from his early twenties to his eighties was an intimidating task, and one that was also quite ludicrous for a number of reasons, but which Scorsese and De Niro managed to easily overcome by engaging with the character, and the idea of telling this kind of story, in ways previously unheard of. There is more to this performance than the state-of-the-art technology that allowed the actors to appear much younger, a certain underlying sincerity that De Niro had seemingly lost over time, but which he revives here to the point where we start to wonder why he hasn’t been afforded these kinds of towering roles more often in the past few years, because he is clearly still just as capable as he was in his youth. There’s also a stillness in this performance that separates it from anything De Niro has done before, even in his greatest collaborations with Scorsese. It’s often quite a subtle performance (even if it doesn’t lack some broad moments, with De Niro embodying every aspect of a hitman who will go to any lengths to preserve himself and protect those closest to him), and sees the actor venturing into a more internal space in his performance style. Sheeran is never constructed to be a hero, nor a villain. He’s not particularly likeable, nor is he all that despicable. We can’t even use the justification that he was “just following orders” to make sense of his decisions. He’s a far more complex character than can be placed into a binary category, and the film makes great use of the actor’s natural vigour, as well as an underlying tenderness that can only come with experience.

The approach the film takes to the character is one that is far more complex, and sees De Niro balancing many different aspects of the character – and it’s often in the moments between broad events that mean the most. We’ve already noted it, but The Irishman is not a conventional crime film – there is a lot of it in the film, but the most meaningful moments come from the pauses between the headlines. Sheeran’s family life, his inner concerns and his reflections on aging and death make this is a performance that saw De Niro making great use of his natural intensity, but also demonstrating a certain sensitivity that perhaps doesn’t excuse the actions of the character, but does imbue the role with a sense of tenderness that makes the final act of the film so heartbreaking, because ultimately, as he mentions towards the end of the film, everyone has their time to go, even those who think their wealth, power and influence make them immortal, where one’s reputation can only be kept alive through faint memories. The film’s delicate way of using a gangster story to be a profound meditation on mortality and coming to terms with the volatility of life makes this a layered piece, where Scorsese uses the space not to glamourize crime (as he has often been accused of doing, with some of his films being dismissed as justifying the sordid lives of despicable individuals), but to provoke certain existential themes, all of which come about in the way he portrays ageing. The Irishman just would not have worked had other actors played the younger versions of the characters – the slow decline in their physicality, their gradual journey into old age and their sudden realization that they’re not going to live forever could only be possible had these actors played the roles throughout, as the intricacies that come with the roles being inextricably tied to the people playing them.

Acting across from De Niro is an extensive cast of supporting performers, some of which have worked with Scorsese before, others making their first foray into collaborating with the legendary filmmaker. Two of the most significant parts, as we’ve alluded to already, come on behalf of Joe Pesci, also reuniting with Scorsese for the first time in nearly a quarter of a century, and Al Pacino, who surprisingly works with the director for the first time, despite both being pivotal figures in the rise of New Hollywood. The Irishman is such a well-constructed film, and one of the most impressive aspects of it is how it oscillates between De Niro and his relationship with these two actors. Like De Niro, both Pacino and Pesci are giving exceptional performances, with Pesci, in particular, hitting a career-best with his beautifully subtle performance as Russell Bufalino. The film explores this ménage à trois of deviance and criminal behaviour in such intricate ways, weaving a web that gives the actors so much to work with. They’re not just criminals, but complex, fully-formed individuals on their own, which makes their interactions so fascinating. Pesci and Pacino also could not be more different in their style of performance here – Bufalino is more subdued, whereas Hoffa is just as vivacious as his reputation suggests. Pacino is an actor who has certainly demonstrated himself to be excessive at times, but his Hoffa is his most nuanced performance in years. He shows great restraint, even when the role calls for overabundance, and while Hoffa is understandably the most unexplored of the main characters (which was by design, as so much of his reputation depended on how he was a larger-than-life public figure, but whose personal life was almost entirely unknown), Pacino and Scorsese create a truly compelling character that serves as a somewhat endearing character with just enough villainy embedded in his behavior to avoid sympathy. Pesci, on the other hand, gives an astounding performance that sees the actor delivering arguably his best work – he takes a character that would otherwise just be an archetypal crime boss, and instead constructs a compelling character who is not just a vindictive criminal looking for wealth or influence, but also a man doing what he knows best, regardless of the immorality that comes with it. Pesci has simply never been better, and he stands as the heart of the film, being at the core of some of the most unexpectedly moving moments. What makes The Irishman so brilliant is that despite De Niro being in the vast majority of the film, it isn’t only his story – the film depends just as much on Pacino and Pesci, and to reunite these actors, as difficult at it may have been, was most definitely worth the cost, as what they do here is simply unprecedented.

The Irishman is also worth acknowledging as Scorsese’s attempt to redefine the crime genre in a way that felt organic, taking it in new directions while still keeping the spirit of the genre alive. He takes many aspects of the traditional gangster film, and looks at them from very different perspectives, most notable the violence (presented here not as energetic, somewhat sensationalized sequences, but rather as bare, straightforward outbursts of pure anger and vindication, which are neither glamorous nor entertaining, but rather harrowing and uncomfortable), and the inner machinations of organized crime, which is normally perceived as being a life of luxury. The film mainly stays away from the beautiful mansions and clubs that these kinds of individuals are normally shown to frequent – The Irishman rather finds itself occupying the spaces between traditions, both physically and metaphysically. This is all used by Scorsese to challenge the boundaries of an ordinary crime film and to subsequently allow it to venture deep into the mind of Frank Sheeran, and question the one theme the film is most intent on exploring: morality. The Irishman isn’t a conventional tale of the rise and fall of a powerful but violent man, but it does take the form of the traditional morality tale, insofar as a large portion of this film, perhaps the most significant parts of it, demonstrate introspection on the part of the protagonist, particularly in the framing device that allows him to give his own testimony. Whether or not what he said is true (this is where The Irishman starts to take a turn towards being an absurdist comedy, as some of the events depicted here, and the conversations that occur alongside them, are so ludicrous, they can only be true) isn’t the concern of the film – but the inner quandaries that plague Sheeran certainly are.

The film operates at a much higher level in terms of how it explores the moral underpinnings of gangsterism – it doesn’t need to ask if these actions are right or wrong, but rather questions the extent to which ordinary people will go to earn respect and affluence, and whether or not it’s worth it. There are many moments of self-reflection in The Irishman, but few of them as profound as Frank stating, after being arrested, “I loved that car – but it wasn’t worth the eighteen years they gave me”. The final chilling moments of the film shows that this is not just a crime epic – it is a deeply intimate character study, a story of an ordinary man, albeit one in extraordinary circumstances. Throughout the film, he gradually becomes older and starts to realize his own mortality, as do all of the other characters who find themselves in equally precarious positions, caught too deep in the culture of criminality to ever hope to fully escape from it. The film never even attempts to demonstrate how any of these individuals tried to redeem themselves – it paints them as individuals engaged in a business that they knew was dangerous, acknowledging how crime syndicates inevitably have to resort to some kind of betrayal, even by those who we are most loyal to. There’s an underlying melancholy to this perspective, and we could even look at the way this film ends, how we see Frank gradually coming to terms with his impending death by choosing his coffin and selecting his burial place, that shows that the most appropriate way for a film like this to end is, to manipulate a phrase, not with a bang of a gun, but with the whimper of an old hitman slowly realizing that he’s on the precipice of death, asking himself quite earnestly: was it all worth it?

The Irishman as film is a rousing success for so many reasons, as I’ve outlined in this review – it is a tightly-written, beautifully-composed gangster film that sees the reunion of some of the defining figures in New Hollywood, working together again for the first time in decades, proving themselves to be still very much at their peaks, even if they all occupy a more mature and somewhat world-weary position, which gives the film even more nuance. However, more than anything else, it’s a potent reminder that Martin Scorsese is most definitely one of the greatest artists to ever work in the medium of film, and with this, he not only delivers the year’s best film, but also one of the finest films of the decade, and a personal best for a director who has given us so many masterpieces throughout the year – and it wouldn’t be surprising to see this come to be seen as his masterpiece. It sees all of his strengths colliding beautifully – an intricately-woven crime story that delves deeply into the core of gangsterism, a compelling character-driven piece that gives it’s extensive cast a great deal to work with, and an existentialist drama that sees the filmmaker provoking some very unsettling themes in his pursuit of a complex portrait of the human condition. The Irishman just can’t be dismissed as a crime film – it is so much more, and this is most definitely the epitome of great filmmaking and something that will stand as one of the most extraordinary examples of cinematic artistry ever produced. It has lingered in my mind, and shows absolutely no sign of relenting, which is very welcome, especially when it is done by a film so poignant, powerful and incredibly moving, it becomes an almost spiritual experience. The Irishman is a masterpiece in every sense of the word.

In 1983 Woody Allen made a brilliant but little respected 79 minute comedy called Zelig. The film follows a non-descript everyman who turns up in some of the most compelling historical moments of history for that period.

On the surface, that is The Irishman. Robert DeNiro plays Frank Sheeran, an average goomba who is taken under the wing of a powerful player in the Mafia. Like Leonard Zelig, Frank appears on the edge of historical events of his time period.

Of course, Zelig is a brief piece of art that floats across the silver screen in a momentary flicker of light and sound. The Irishman, in contrast, is rather sedate and contemplative. Too often it sits leadenly on the screen inert and repetitive.

In 1983, Zelig was regarded as a technical oddity. Only with time did appreciation for the filmmaking wizardry that places Woody Allen into actual newsreel footage gain admiration. In The Irishman, the much ballyhooed de-aging effects have the public’s eye. For me, every unlined face still rests upon a slow moving, lumpy, clearly aging body. The novelty of younger faces on great actors is a distraction. Too often the actor’s hands, dead giveaways of age, brush past the face. For longer moments, the hands are de-aged but not always. Reality intrudes.

At the end, a priest sits with Frank and asks if feels regret for his actions. Frank turns and states that he didn’t care.

Me, either.

Beyond masterful work from Joe Pesci, this film is merely a longwinded indulgence from old men trying to recapture their youth.