Before he became the concept-obsessed perfectionist we revere him as today, Stanley Kubrick was a filmmaker concerned primarily with smaller stories that focused on more human subjects, operating on a much more intimate scale. However, his first foray into more ambitious filmmaking occurred at the nexus between his more gritty, low-budget stage and the period of meticulous detail and high-concept ideas, in the form of Paths of Glory. Part war film, part courtroom thriller, part existential drama, Kubrick constructed arguably one of his finest works, a scathing indictment on war and the atrocities of combat, not necessarily on a national or cultural level, but rather in terms of the individuals and the effect such periods can have on someone, as we are introduced to a variety of soldiers suffering under the traumatic conditions of a war no one should have to be fighting, but being nonetheless dedicated to the cause of defending their country, no matter the cost, even if it means their lives. Kubrick made his first definitive statement as a filmmaker here, and would go on to only develop his craft from this point onward – not to invalidate his earlier work, but rather to comment on the nature of this film, which sees him abandoning the title of “director-for-hire” and becoming an auteur all on his own terms, and there was genuinely no better film to begin his journey to acclaim than Paths of Glory.

Before he became the concept-obsessed perfectionist we revere him as today, Stanley Kubrick was a filmmaker concerned primarily with smaller stories that focused on more human subjects, operating on a much more intimate scale. However, his first foray into more ambitious filmmaking occurred at the nexus between his more gritty, low-budget stage and the period of meticulous detail and high-concept ideas, in the form of Paths of Glory. Part war film, part courtroom thriller, part existential drama, Kubrick constructed arguably one of his finest works, a scathing indictment on war and the atrocities of combat, not necessarily on a national or cultural level, but rather in terms of the individuals and the effect such periods can have on someone, as we are introduced to a variety of soldiers suffering under the traumatic conditions of a war no one should have to be fighting, but being nonetheless dedicated to the cause of defending their country, no matter the cost, even if it means their lives. Kubrick made his first definitive statement as a filmmaker here, and would go on to only develop his craft from this point onward – not to invalidate his earlier work, but rather to comment on the nature of this film, which sees him abandoning the title of “director-for-hire” and becoming an auteur all on his own terms, and there was genuinely no better film to begin his journey to acclaim than Paths of Glory.

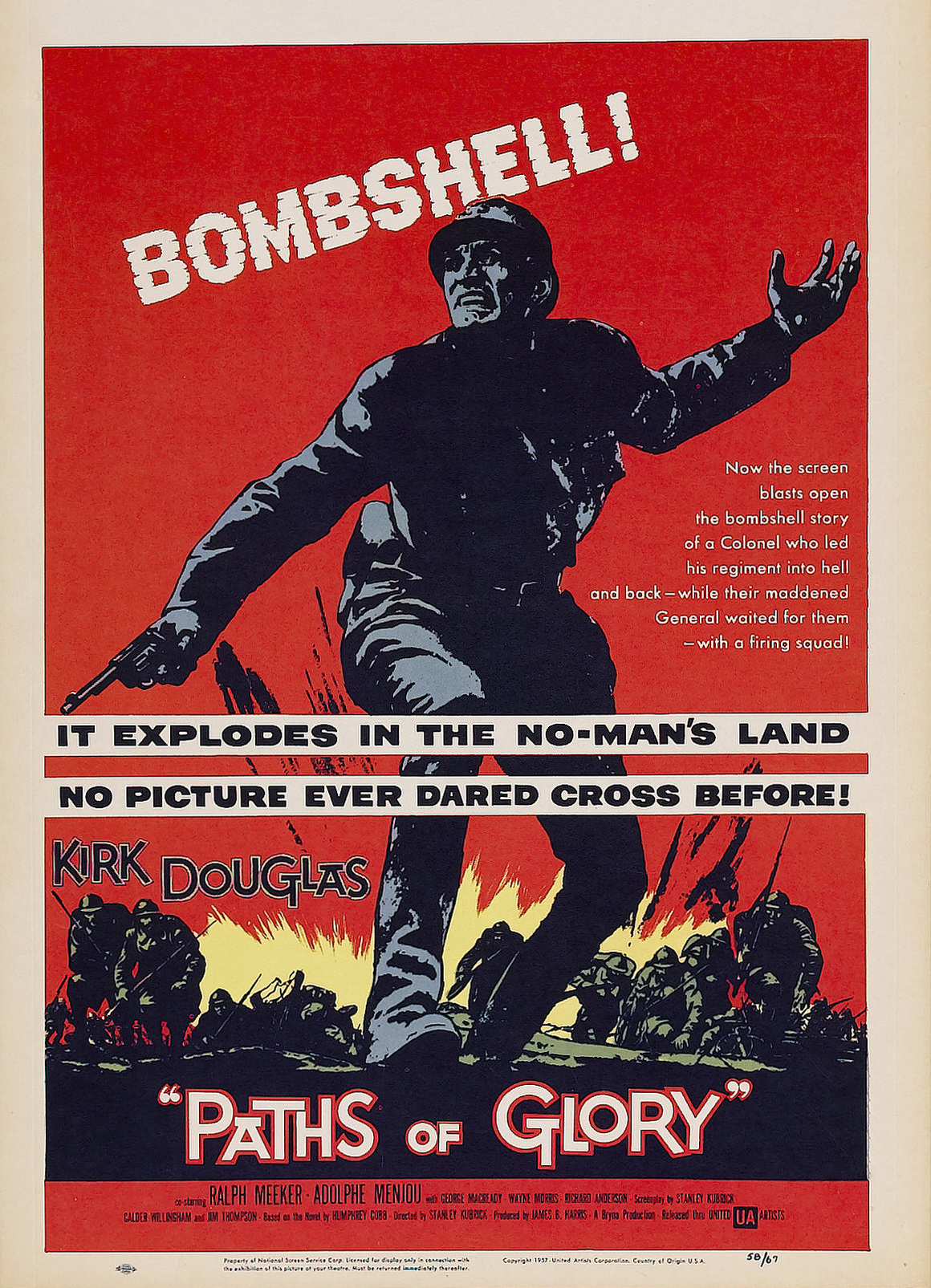

Set during the First World War, we are taken into the trenches that serve as the shelter for the French Army. Leading them with a blend of bravery and elegance is Colonel Dax (Kirk Douglas), a former lawyer doing his part for his country by serving in the war. When a command is passed down, it is his responsibility to execute it, which is made difficult when he is told that he needs to lead his men on a suicidal mission to storm and capture a German military base across the battlefield, where it is almost certain that over half of his soldiers will be killed, as they are weak, diminished and incapable of such a dangerous mission. When it fails dismally, in no small part due to the inefficiency of the plan and the lack of preparation, as well as the unlikeliness of success, Dax is put in a precarious position after they lose the battle: three soldiers have to be selected to be put on trial for cowardice in the face of the enemy, with the three soldiers chosen (Timothy Carey, Joe Turkel and Ralph Meeker) not only being entirely innocent, but also having shown bravery before, which is invalidated by the request of the French military authorities to make an example, if only to boost morale and to convince their fellow soldiers to start displaying more motivation to defend their country. Dax, trying his best to not see innocent soldiers perish for a ludicrous display of military force, takes on the role of defence, and does his best to prove that they don’t deserve to be put to death as punishment – but when it appears that all is fair in love and war, he struggles to convince the warmongering authorities to exercise some compassion.

There is a lot to unpack with Paths of Glory, which is quite certainly a film that features a lot of content that goes deep into the roots of the human condition (despite being nearly a half the length of most of the director’s subsequent work) and explores the ravages of war, and the weight it can have on the human spirit. Adapted from a novel of the same name by Humphrey Cobb, Paths of Glory looks to be a scathing commentary on armed conflict, and how it is far from being the triumphant, joyous representation of national unity that so many people claim it to be. The adage is old but true: history is written by the victors, which certainly is exactly the opposite of what Kubrick and his cohorts were trying to represent here, whereby history is defined by losses, and society as a whole, or rather innocent members of that society, tend to be punished for it. Another sentiment that may be trite but stands to be very true for the message of this film is that in times of war, there are no winners or losers – even those who are victorious have to suffer the consequences of involvement, whether it be through heinous crimes against their fellow man, or simply the trauma of having taken part in something as horrific as war. Paths of Glory is far more interested in the latter category, specifically looking at the decent and honourable men who served in the war, followed orders but tragically met their demise through virtue of just being involved.

At the forefront of this film is Kirk Douglas, who gives one of his finest performances as the heroic Colonel Dax. It is a remarkable performance, mainly because despite being a man who demonstrates great bravery and dedication to his country in the time of war, he is not the archetypal valiant hero. Rather, he is a conflicted man, someone who does not enjoy warfare (unlike his direct superiors, who consider it to be a game of sorts, which is an easy sentiment when spoken from the luxurious military châteaux, far from the trenches), but understands that he needs to serve his country – but it soon becomes clear that it isn’t merely the flag that Dax is intent on protecting, but the individuals who pledge allegiance to it. Hence, when a failed mission results in a court-martial, he is intent on defending the honour and lives of the men forced to be punished. Douglas is at his most empathetic in Paths of Glory, leading this ensemble with a combination of quiet rage and intense compassion. It is a wonderful performance from an actor who had an uncanny ability to derive a range of complex emotions from even the most inconsequential of moments, and whether in his impassioned speeches, or his subtle expressivity, it is a heartwrenching but brilliant portrayal of a man doing whatever he can to protect the people who unfortunately find themselves becoming victims of war, albeit in the most unexpectedly perverted way possible. Exceptional supporting performances from Ralph Meeker, Joe Turkel and the brilliantly unconventional Timothy Carey, amongst others, give Paths of Glory a sense of cohesion, with an ensemble fiercely dedicated to conveying this harrowing message.

Paths of Glory occupies an ambigious area in terms of classification – it certainly is a film about war, but separates itself from plenty of other films with similar subject matter, solely because it never attempts to justify what it depicts. This is not the rousing film about overcoming difficulties in the face of life-altering challenges, but rather an acidic derision of war and everything it stands for. Like the author of the novel, Kubrick is demonstrating that war is not something to celebrate, but that doesn’t mean the individuals who put their lives on the line should not be appreciated. The film is primarily focused on one faction who are indicted for apparently showing “cowardice in the face of the enemy”, which is hypocrisy in its most evident form, especially due to the fact that the person passing that order down was comfortable in his bunker, far from the battlefield. The men depicted at the heart of Paths of Glory are shown to be the bravest of souls, as they have to demonstrate courage in the face of impending demise, being punished for being unable to execute a mission that was doomed from the start. Soldiers, to the high-level officers, were nothing but disposal entities, as demonstrated very early on when the main antagonist casually mentions the likely deaths Colonel Dax and his men will face as just objective statistics. Kubrick balances the film’s steadfast anti-war message with a more sentimental view of the soldiers who doubtlessly faced unrelenting fear during this period. A chilling moment comes towards the end of the film when Meeker’s character breaks down in front of the man who will be assisting in his impending execution and is calmly told: “many of us will be joining you before the end of this war”. It would be extraordinarily difficult to not be moved by this film, with the affectionate approach to representing their plight sometimes being somewhat manufactured, but never being particularly saccharine. The bleak subject matter is only resolved by the ending, which indicates that there is some form of hope in a world filled with despair.

Ultimately, we can’t neglect the fact that as simple a film as this is, it still hails from the brilliantly demented mind of Kubrick, who crafts a very experimental war film that sets this apart from other works in the genre, not only in its message but also in its broader execution. His style elevates Paths of Glory from being just a glorified piece of anti-war propaganda into a visually-beautiful, complex film that fixates on certain ideas with a fierce dedication only possible from someone as assured as the director. Paths of Glory doesn’t look like a traditional war film, mainly because all the elements that are normally presented as triumphant and riveting are repurposed to be gritty and harrowing, such as when Kubrick tracks through the trenches, where the audience sees the ravages of war, and the fear evoked during such attacks, explosions occurring regularly. The centrepiece of the film is the attempt to take the Ant Hill, which is one of the most gorgeous battle scenes ever produced, albeit one that is more harrowing than it is enthralling. A single shot follows Colonel Dax and his men as they run through No Man’s Land, with bodies falling regularly around them, and the barrage of deafening bullets taking down hoards of innocent men. Paths of Glory is a highly disturbing film, and the way in which the tragedies of war are represented are effective because Kubrick places the audience right in the centre of the trenches, or on the battlefield, where we are passive voyeurs to the unsettling combat that takes more victims than it does produce victors.

Paths of Glory is a film that won’t soon be forgotten by those who watch it because it is a work of disconcerting brilliance. It may be an earlier work by a director who came to be defined by more bombastic, excessive works, and while this one certainly does contain much of that same audacity, it is a far more subtle, straightforward and subdued affair that flourishes on its intimacy and empathy, which are mostly absent in Kubrick’s subsequent works (not necessarily a shortcoming, but just an observation). Bleak but not without some semblance of hope, this film makes a powerful statement, remarking not only on the tragedy of war, but on the hypocrisy on those who incite it, the individuals who see combat as nothing more than an elaborate sport, where the citizens they purport to be protecting are just pawns in their displays of strength and power, and the arrogance that comes with the choice to defend one’s honour rather than concede to an unfortunate mistake. Powerful and heartbreaking, Paths of Glory is quite simply one of the greatest films on the subject of war ever produced, mainly because it doesn’t look at it from the perspective of celebratory bias, nor does it ever demonstrate that it is something that any country must be proud of being a part of. It is a simple but effective film that leaves a lasting impression, and through the most subtle means, gets to the root of not only the mentality of the individual, but the consciousness of society as a whole, and how it tends to be irreparably damaged in times like this. This is a beautiful, poetic and heartbreakingly honest film, and perhaps the only film that comes close to presenting audiences with an authentic glimpse into something absolutely no one should ever be made to experience.

Arguably, the collaboration of director Stanley Kubrick and actor Kirk Douglas resulted in the apex of each filmmaker’s artistic efforts. Paths of Glory and their subsequent effort Spartacus were vibrant, magnificent successes.

Douglas is worthy of particular note in Paths of Glory. An actor who all too frequently stumbled into over the top indulgences is perfection here. Colonel Dax’s rage, courage, and the erosion of belief brew beneath the surface in a masterful complexity of emotion that Douglas manages to brilliantly underplay. He deserved an Oscar for this performance. After his second contentious collaboration with Kubrick, Spartacus, Douglas never achieved such artistic highs.

I contend Kubrick also achieves his greatest artistic triumphs in concert with Douglas. Both men had great admiration for the other’s talents. However, their ability to identify their flaws in the other brought of the best. Douglas’s tendency for using labored breathing to convey emotion was tempered as was Kubrick’s insecurity pushing him to film scenes to an excess resulting in airless perfection. Paths of Glory is particularly alive and vital.

These fine films were born from acrimony. Kubrick and Douglas battled voraciously to curb the excesses of the other. Anne Douglas grew so concerned by the intensity of these arguments that she urged her husband and Kubrick to enter therapy to preserve their mutual respect as well as develop as a healthy working relationship. On a side note, it was in these sessions that the therapist suggested Kubrick read the 1926 novel Traumnovelle which served as the source material for Kubrick’s final film Eyes Wide Shut.

Following these two outstanding films, Kubrick and Douglas never worked together again. Douglas’s career denigrated into a tired string of roles as cowboys and aging lotharios. Kubrick became noted for casting marginally talented pretty boys (Malcolm McDowell, Keir Dullea, Tom Cruise, Matthew Modine) who did not offer the challenges Douglas brought to the set.

And perhaps the termination of their collaboration was for the best. Kubrick’s next film was his adaptation of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. While the concept of Douglas playing pedophile Professor Humbert Humbert is intriguing, it would certainly have been morally repugnant. Given Natalie Wood’s allegation of Douglas raping her while she was still underage and her mother waited in the car outside Douglas’s home, James Mason was preferred casting.