Robert Altman made the films no one else was willing to make, and the ones very few were able to even conceive of. In his long and storied career, the director crafted films that spanned genres, nations and even the occasional dimension. His films were sometimes not even all that good, but still managed to be fascinating pieces of social or cultural commentary, and became landmarks of their respective eras. Altman was at his peak in the 1970s, which is precisely when he made the film that is arguably his greatest achievement – Nashville is the very reason why cinema means so much to me. It is a beautifully-composed musical satire that is simultaneously tragic and hilarious, heartfelt and harrowing, and a journey into the depths of the human spirit, done in a way very few directors would ever attempt. Altman was an audacious filmmaker, in this nearly three-hour-long musical odyssey into the birthplace of country music, he provides the audience with one of the most enthralling and complex explorations of social issues of the 1970s. He is one of those directors who doesn’t have one standout film, but rather a career of phenomenal pieces. Yet, Nashville will always stand as his magnum opus, a beautiful work of New Hollywood filmmaking that never backs down from its steadfast celebration of life and its inconsequential idiosyncracies, which all add up to form a brilliant mosaic of existence. Nashville is quite simply a masterpiece, and one of the greatest works of filmmaking to come out of the 1970s.

Robert Altman made the films no one else was willing to make, and the ones very few were able to even conceive of. In his long and storied career, the director crafted films that spanned genres, nations and even the occasional dimension. His films were sometimes not even all that good, but still managed to be fascinating pieces of social or cultural commentary, and became landmarks of their respective eras. Altman was at his peak in the 1970s, which is precisely when he made the film that is arguably his greatest achievement – Nashville is the very reason why cinema means so much to me. It is a beautifully-composed musical satire that is simultaneously tragic and hilarious, heartfelt and harrowing, and a journey into the depths of the human spirit, done in a way very few directors would ever attempt. Altman was an audacious filmmaker, in this nearly three-hour-long musical odyssey into the birthplace of country music, he provides the audience with one of the most enthralling and complex explorations of social issues of the 1970s. He is one of those directors who doesn’t have one standout film, but rather a career of phenomenal pieces. Yet, Nashville will always stand as his magnum opus, a beautiful work of New Hollywood filmmaking that never backs down from its steadfast celebration of life and its inconsequential idiosyncracies, which all add up to form a brilliant mosaic of existence. Nashville is quite simply a masterpiece, and one of the greatest works of filmmaking to come out of the 1970s.

The simplicity of this film’s title is not misleading at all – what Altman seemed to be attempting to do with Nashville was to present us with a sprawling musical epic that covers the entire region and looks at a group of people all vying for fame and fortune in the heartland of the American music industry. The film weaves together the stories of over two dozen people, both outsiders and residents of the famed capital of Tennessee, and depicts their various trials and tribulations in the days leading up to a major rally for an enigmatic political figure who is trying to win the presidency. Two dozen characters, two dozen individual stories of people searching for fame, wealth, power and more than anything else, a sense of belonging. The music industry is evidently a very difficult one – just look at the countless works that have looked at scrappy young musical prodigies struggling to find their way in a cutthroat world that destroys ambitions just as fast as it makes dreams come true. In Nashville, we see veterans who are already at the top questioning their next chapter, and newcomers who are trying so desperately to make it into the industry. Throughout the film, they interact, learning from each other and taking advantage of the hustle and bustle of a city that quite literally has music pulsating through its veins. This quaint Southern metropolis is the stage for triumphs and heartbreaks, moments of rousing victory and scenes of wrenching tragedy, all of which Altman presents to us with his trademark blend of humane empathy and vitriolic sarcasm, which makes for a truly riveting experience.

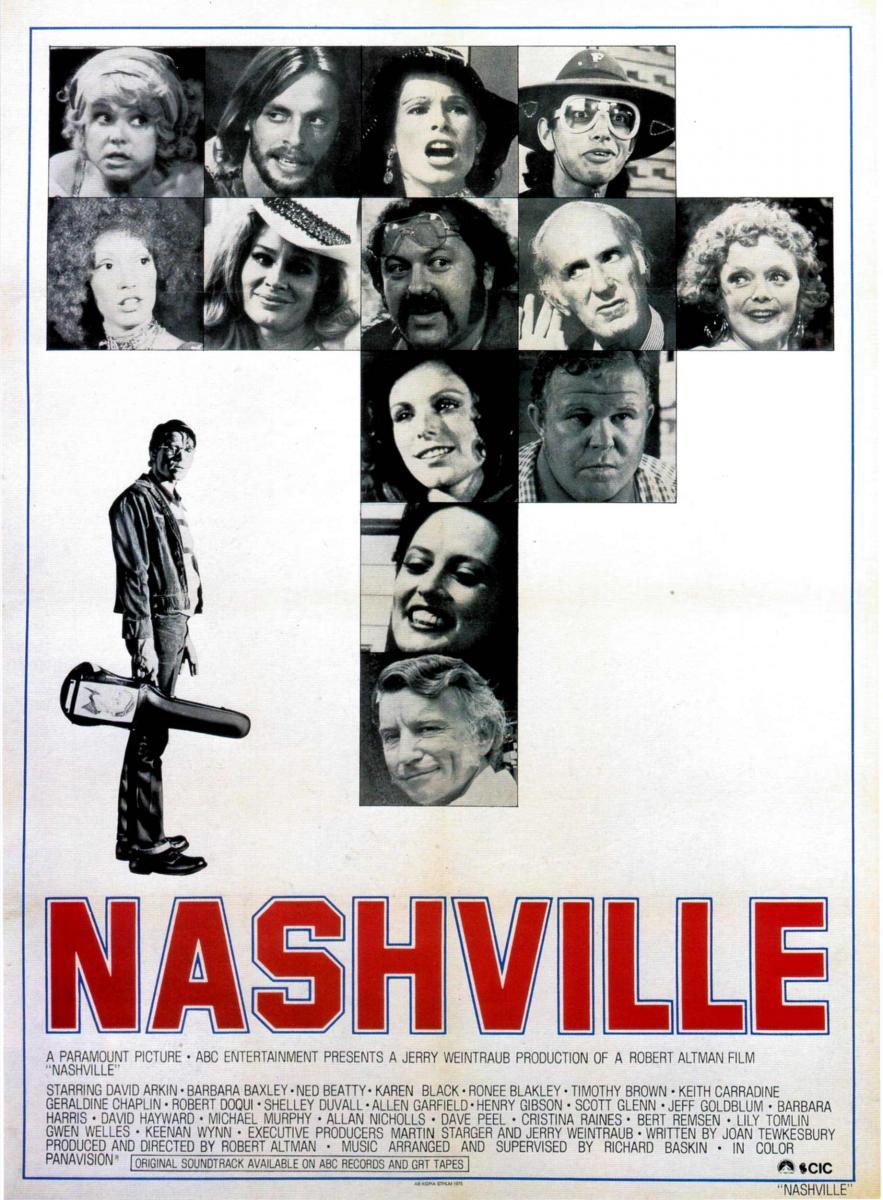

Altman truly had a way with actors – considering he was the director who managed to make films that range from having only a single actor (such as Secret Honor) to those that have dozens of performers making their way through the story. Nashville was the first of Altman’s major ensemble films and the one that pioneered the style commonly known as Altmanesque (referring to an extensive cast of actors playing a variety of roles, and interacting through their relationship to a common overarching theme). The problem with these kinds of films is that everyone is given equal attention, which means there is a lack of focus on any particular member of the ensemble – and considering everyone in Nashville was astonishing, finding a standout is almost impossible. Everyone has indicated that one or two performances lingered with them the most, and that’s certain true, because while we can acknowledge that this film, by virtue of its design, was not meant to have any individual performances dominate the other, some of them seem to make more of an impact than others, but that’s entirely on the discretion of the viewer, who is naturally drawn to some of them. It really is indicative of a great ensemble that is operating extremely well when you can through a proverbial dart into any scene and hit an astoundingly great performance. It is very unlikely that there are any casts from this era that are much better than what we see in Nashville, and Altman’s incredible sense of cohesion when it comes to working with actors (and how he gets them to act across from each other) makes for something extremely special.

In terms of my favourites from the cast, it is difficult to choose, but it is not entirely impossible. Barbara Harris is an actress who has yet to disappoint me (and considering she gave two of the best performances of 1976 in Freaky Friday and Family Plot, it is clear that she was at her peak in the 1970s), and in Nashville she is playing against type as the calculating, sycophantic Winifred, who will do anything to catch her big break. Mostly in the background for the majority of the film, Harris’ is a scene-stealer, albeit one that isn’t given much substance for the majority of the film. Considering there are reports that the actress was sorely disappointed with her performance to the point where she offered to pay for reshoots, it is understandable that one would think that she wasn’t given anything to do – that is until the final scene, where we hear Harris’ character sing for the first time – and not only is her performance of “It Don’t Worry Me” the best song included in Nashville, it is the definitive scene of the film, the moment that brings everything together, and allows the film to end on a note of hope. Harris, however, is somewhat overshadowed by the performances of Lily Tomlin and Ronee Blakely, who have the roles that are most fondly remembered. Tomlin abandons her exuberant, quirky comedic persona to play a sweet-natured gospel singer who is solely focused on raising her deaf children to have the best life possible, and who starts to question if her marriage is worthwhile, especially with the arrival of the aloof and mysterious Tom (Keith Carradine). Blakely is the tragic core of the story, playing the troubled Barbara Jean whose life has been one tragedy after the other. She is the closest to a protagonist that this film has – the film begins with her arrival, and ends with her departure, her story bookending the film and giving it nuance. Yet, it feels wrong to mention some performances and not others – but its also almost impossible to dissect each and every actor’s portrayal in Nashville, not only because they’re all so unique, but also because there are far too many noteworthy performances scattered throughout this film. Ultimately, Nashville is a marvel purely because it extracts astonishing performances from an immense cast, each of which is given moments of significance that remain truly memorable.

Nashville also features Altman at his most experimental – even just looking at the production of this film, we can see how innovative it was. Apparently large improvised, and featuring actors tasked with writing and performing their own material, Nashville has a certain gravitas that would have been missing had the actors themselves not been equally able to explore their own characters. Altman and screenwriter Joan Tewkesbury may have created the characters (which were in turn based on real-life Nashville figures), but the performers themselves took on the difficult task of giving their characters depth and nuance all the while being committed to this film’s enormous scope. There are few directors who are able to pull off such a bold form of character development through putting it directly into the hands of the performers themselves (its something Mike Leigh is particularly adept at), but Altman does exceptionally well – and despite the potential for the film to be derailed by ego or attempts to bolster one’s character in terms of the role they play, Nashville is relatively cohesive and straightforward – it speaks not only to the generous merits of a director who had absolute faith in his cast, but also an ensemble of talented performers who could fully embrace the added challenges put upon them to help build their character and contribute to a massive ensemble. The fact that Nashville was a career highlight for nearly everyone involved is not an accident and comes from the fact that each individual was given the chance to develop their individual role in a way that not only suited them but the film as a whole. It’s daring, bold and utterly brilliant, and proves the inherent genius underlying this extraordinary film.

Yet, what is it that makes Nashville so special? Musically, it is astonishing – one doesn’t need to be a fan of country music to appreciate the artistry that went into this film, especially because the intention of this film is not to celebrate country music specifically, but rather the various individuals who are united under one common genre, and how music serves to bring entire populations together. Altman certainly did not abandon his notorious perfectionism in making Nashville, because he demonstrated his clear intention to explore the country music capital of the world through actually making an effort to include music as a primary component of the film – featuring a soundtrack composed of almost entirely new compositions (all of which, as we’ve mentioned before, were written and performed by the actors themselves), Nashville is a film that focuses on the celebratory nature of music, and how it is a universal language – whether patriotic or critical, heartbreaking or entertaining, rowdy or subtle, music has the power to unite like no other force in existence, which is what makes Nashville so compelling – the characters in the film are simply searching for some meaning, which almost always manifests through their tendency to express themselves through music – nearly everyone in this film is musically-inclined, whether they perform it, write it or are simply radically interested in it to the point where just being in the proximity is more than enough. The best moments in Nashville tend to be the musical performances – what would this film be without the catharsis of Keith Carradine’s “I’m Easy”, or Henry Gibson’s rousing patriotic anthem in “200 Years”, or the aforementioned “It Don’t Worry Me”, which is one of the most hauntingly beautiful endings of any film from this era, and the moment that brings absolutely everything in this film together. Everything that makes music such a profoundly beautiful means of communication is explored in Nashville, which realizes its full potential without ever wavering from its bold premise and audacious execution.

Yet, there’s something deeper to Nashville that extends far beyond the simple confines of the story. Altman, as we’ve said on numerous occasions, was someone who understood humanity in a way very few directors were able to, and his ability to get into the psyche of the ordinary individual was unprecedented. Nashville may be a film that appears epic – at the outset, the barrage of characters and storylines may be nothing short of overwhelming, and may confuse the viewer – but this is only momentary because we very soon discover there is no broad metanarrative to this story. Nashville exists as a series of small episodic moments, interweaving stories that are able to flourish independently but become something very special when viewed as a broader tapestry that depicts a time and a place, with the implications of the underlying message being one that is profoundly resonant. Nashville is a truly easygoing film – it is quite long, but it serves the purpose of being an event in itself. This is not a minor film that is just watched and forgotten – its an entertaining, enthralling portrayal of life in its most simple and condensed form, and an often extremely poignant exploration of the simplicity of existence, and how we are all on our own individual journeys that usually do overlap in ways we wouldn’t expect. This is the genius of Nashville – it is essentially an anthology film, but one where all the stories occur concurrently. The intelligent structure of this film is not to be underestimated, with Altman’s deft skill at balancing two dozen stories with equal ease and flawless brilliance being the precise reason behind this film’s success – its one thing to have a committed cast that can bring life to these stories, but without a director who is able to juggle all of them and present them in tandem, this film had the potential to be a disaster. Thankfully, the opposite is true, and this is undeniably one of the greatest cinematic experiments of its era.

Nashville is an astonishing film, and its status as one of the greatest of all time is certainly not undeserved. This is a film that simplifies life and presents it to us in a way that is honest and to the point, showing us that sometimes the most insightful revelations come in the smallest, most inconsequential moments. Altman has crafted one of the most authentic films of the 1970s, a work that lacks even the smallest trace of a false note anywhere. There have been many attempts to classify one work in particular as The Great American Film – and it might be possible to assign such a daunting title to Nashville – not only does it have the scope of a great generation-spanning novel, it takes the approach to get to the root of the American Dream, showing how it means something different to everyone – the film starts with Gibson singing a powerful patriotic anthem about America’s trials and tribulations, noting that despite all the hardships that the nation has experienced, they “must have done something right to last two hundred years”, which can be contrasted by the ending, where we see someone brutally shot down in broad daylight, with such a tragedy overcome with the uniting of diverse voices through music, with the American flag waving proudly in the background. Nashville doesn’t ignore the problems that inflict the American public, but it does admirably in showing that despite all the hardships and trouble, there is a nation of beautiful spirits and audacious souls that are all working together to realize their own individual goals, reaching their own definitions of success, and finding the inner peace to say they are proud to be American. Nashville is an astonishing film – Altman takes on a challenging concept, and manages to deliver a film that is enormous in both intention and execution, yet he manages to condense it into one of the most entertaining pieces of the 1970s, a calm and sedate exploration of the cultural zeitgeist, which has never been more profound nor more gorgeous than through the perspective of one of cinema’s great social visionaries.

Nashville is an iconic film.

That stated, not everyone developed their role. Louise Fletcher was originally slated to play Linnea Reese, the gospel singer with deaf children. Fletcher, as most Oscar fans recall from her acceptance speech in sign language to her deaf parents, intimately understood the challenges of a household with hearing and deaf members. She worked for a long period on developing the character of Linnea.

Fletcher had previously appeared in Altman’s Thieves Like Us, an unsuccessful effort written by Nashville scribe Joan Tewksbury. Fletcher’s husband Jerry Bick produced Thieves Like Us as well as Altman’s previous film The Long Goodbye. When the producer and the director had a falling out, Fletcher was replaced by Tomlin. Since this was also the year of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, had Fletcher stayed in Nashville, it would have a remarkable pairing.

In the summer of 1975, I went to the best cinema in town to see Nashville. The cavernous auditorium seated over a thousand. The smattering of four or five other movie goers sat silently as we watched what I quickly came to believe was a profound artistic achievement. Following the ending, an unexpected event that left me devastated, I wandered into the empty parking lot. Only then did I cry. Here was one of the greatest cinematic experiences of my brief life, and no one was coming to see it.

Flash forward decades later. I am treating my son to a meet and greet in San Francisco. Stars and film makers of classic sci fi and horror films are seated in a series of buildings. They have posters and head shots piled on tables. For a fee, my happy teen can have a moment with his favorite moviemakers. I am standing off to the side feeling the smug satisfaction of being a good dad and doing something my own father would never have done for me.

Amid the series of long lines I noticed a table with a lone woman and no line. The sign advertised the opportunity to meet Ronee Blakley star of A Nightmare on Elm Street. I pulled two twenties from my wallet and approached the actress who so moved me in 1975 and continued to do in repeated viewings of the film.

As I drew close and before I spoke, she smiled and greeted me, “Ahh, my Nashville fan. There’s always one at these events.” She was gracious and kind. She listened to my words of exuberance for her work as Barbara Jean and shared some of her favorite memories from the shoot. She politely rebuffed my inquiries about her ex husband Wim Wenders and graciously thanked me for remembering her.

As I left, I saw no one else was waiting to meet the actress who gave one of the most indelible film performances of the 1970s. For a brief moment it was 1975, and I was again standing in an empty parking lot outside a movie theater showing Nashville and wondering how great art can be so cruelly ignored.