Over the course of a very prolific career, Steven Soderbergh has made a remarkably diverse set of films, ranging in genre and subject matter, bounding from convention to convention in a filmography that many filmmakers cannot attest to. Personally, I have a contentious relationship with Soderbergh, insofar as I oscillate between considering a true genius of cinema, someone who is chamelionic in how he chooses his films, moving between genres with almost flawless ease (I don’t even need to mention his variety of films, because it seems every film he makes is radically different from his last), or thinking him to be an artist with potential that he is still trying to achieve, an auteur in search of a solid theme, which he has yet to find, as evident by his constant shift between conventions, whereby it seems like his attempts to be diverse are simply efforts to find a niche, because as good as most of his films are, I don’t think any of them can be considered particular masterpieces, and Soderbergh seems to be one of the only filmmakers working today that does not have a definitive magnum opus, specifically because none of his films seem to inspire very much excitement in audiences, regardless of how good they are. One can look to his audacious debut film, sex, lies, and videotape to understand that Soderbergh has always been a fascinating filmmaker – but one that showed that he had the same uneven narrative style and notable flaws right from the outset of his career. I did not particularly adore sex, lies, and videotape, but I found it to be a film that I certainly did admire. It is one of those films that feels like it has some meaning, but it gets lost in the shuffle of over-audacious storytelling, with the film ultimately being a bit of a bore, more than anything else.

Over the course of a very prolific career, Steven Soderbergh has made a remarkably diverse set of films, ranging in genre and subject matter, bounding from convention to convention in a filmography that many filmmakers cannot attest to. Personally, I have a contentious relationship with Soderbergh, insofar as I oscillate between considering a true genius of cinema, someone who is chamelionic in how he chooses his films, moving between genres with almost flawless ease (I don’t even need to mention his variety of films, because it seems every film he makes is radically different from his last), or thinking him to be an artist with potential that he is still trying to achieve, an auteur in search of a solid theme, which he has yet to find, as evident by his constant shift between conventions, whereby it seems like his attempts to be diverse are simply efforts to find a niche, because as good as most of his films are, I don’t think any of them can be considered particular masterpieces, and Soderbergh seems to be one of the only filmmakers working today that does not have a definitive magnum opus, specifically because none of his films seem to inspire very much excitement in audiences, regardless of how good they are. One can look to his audacious debut film, sex, lies, and videotape to understand that Soderbergh has always been a fascinating filmmaker – but one that showed that he had the same uneven narrative style and notable flaws right from the outset of his career. I did not particularly adore sex, lies, and videotape, but I found it to be a film that I certainly did admire. It is one of those films that feels like it has some meaning, but it gets lost in the shuffle of over-audacious storytelling, with the film ultimately being a bit of a bore, more than anything else.

The film takes place in Baton Rouge. Ann (Andie MacDowell) is a bored housewife who is married to John (Peter Gallagher), a highly successful lawyer. The couple are happy on the surface, but there is underlying tension, based mostly on the fact that Ann is unable to be intimate with her husband, who is forced to seek his gratification elsewhere, finding it in Ann’s outgoing, brash sister Cynthia (Laura San Giacomo), whose feisty and dismissive attitude is irresistible to John, who finds her the polar opposite of her more conservative sister. A fourth character enters the fray, Graham Dalton (James Spader), an old school friend of John who is moving back to the area for unclear reasons. John is shocked to discover that Graham is much changed from their time together, living a nomadic, free-wheeling lifestyle, armed with only a few suitcases and the keys to his car. However, as much as John grows disappointed in his friend’s lifestyle, Ann takes a liking to the soft-spoken, intelligent young man, and the pair develops a friendship until Ann learns the truth about Graham: he is impotent, and derives pleasure from photographing woman talking about their sexual experiences. This bothers Ann, who grows disillusioned with the man she was starting to feel some connection to – but when the truth about John and Cynthia’s affair starts to surface, Ann finds herself voluntarily entering into the path of Graham’s video camera, and by proxy, Graham himself.

Here’s my problem with sex, lies, and videotape: it is a film about nothing. It has sex, it has lies and it has videotapes, that’s certainly true, but it seems to lack something imperative, a storyline that the audience can actually feel something towards. The problem isn’t that this is a film that lacks traditional narrative progression, but rather a film that does not seem to have much of an intention, and I’ve been grappling with trying to understand precisely what Soderbergh was trying to say with this film. sex, lies, and videotape is a definitive representation of American independent cinema (being one of the formative films of the movement that still persists today, stronger than ever), and therefore it wouldn’t be right to criticize this film for not having a traditional storyline, because independent cinema was built on a basis of subversion, defying expectations and going against what is considered traditional. In this regard, sex, lies, and videotape is a liberating experience, and a truly wonderful representation of society through a lens that is brutally honest and unflinching towards subject matter that is not necessarily welcome in more mainstream fare. In all of his faults, Soderbergh is at least a filmmaker capable of telling stories in a way that is unique and original, and he certainly exhibited this audacious trait early on in his career. The problem isn’t that sex, lies, and videotape is a bad film – it is that there is a really good film in sex, lies, and videotape, but it just didn’t find it. I felt that this film was almost too selfishly concerned with itself to actually try and be coherent, and while it is not particularly difficult, it is cold and clinical. Yet, considering Soderbergh has been a filmmaker who has distinctively been able to master tone throughout his films, one wouldn’t be wrong to ponder the possibility that the bitter, sardonic nature of sex, lies, and videotape was the intention all along, and looking at it from that perspective, results in this being quite a success, albeit an unbearably uncomfortable one.

sex, lies, and videotape is effective due to the fact that it focuses on a central set of characters rather than an extensive cast. There are essentially only four characters in this film, which makes it an intimate character-driven piece that allows Soderbergh and the audience unfettered access into the psychology of these individuals. James Spader, who is an unheralded actor who deserves better than the television work he has been plying over the past decade, is given one of his first major roles that allowed him to depart the abundance of teen-oriented films that he has been appearing in previously throughout the decade (some of them, like Pretty in Pink, are still wonderful, and he’s great in them). sex, lies, and videotape gives Spader the unlikable but alluring character of Graham Dalton, and while he is the most mysterious character, with his inner workings being closely-guarded, his performance reveals a man who straddles the line between curiosity and perversion. Andie MacDowell, who is quite simply one of the most effortlessly charming actresses of her generation, gives the best performance in sex, lies, and videotape, playing the insecure, frustrated housewife who is caught between two minds – she wants to be a good, decent wife, but she also has underlying curiosity. MacDowell makes this performance, which is not a particularly easy one, seem so effortless, and her endearing nature makes Ann an endlessly fascinating character. Peter Gallagher, who has plied his craft in smaller roles over the years, has a much larger role than normal with John, the troubled lawyer who is struggling to honour his role as a faithful husband and a man with desires, especially considering his wife is seemingly terrified of intimacy, and he seeks out free expression of these desires from Ann’s sister. Laura San Giacomo threatens to upstage everyone else with her beguiling and hypnotic performance as Cynthia, who struggles with her own inner turmoils and existential crises, which she manages to suppress, for the most part, only to have them extracted by Graham and his video camera. In essence, sex, lies, and videotape is a film about a quartet of spoiled, middle-class, yuppie brats who are as unlikable as they are dishonest, but the cast work well together, and interpret these characters in a way that doesn’t make them redeemable, but rather irresistibly fascinating.

As I said previously, sex, lies, and videotape doesn’t promise anything that it doesn’t provide. In terms of the “sex” portion of the title, it is a film that looks frankly and brutally at the uncomfortable concept of human sexuality, something that is not foreign to filmmaking, but from the perspective offered in this film, it is nothing short of uncinematic. sex, lies, and videotape presents the unseen side of sex, focusing less on the romantic or erotic aspect of it, and rather looking at desire from an almost grotesque perspective, interweaving it with voyeuristic qualities. These characters all use sexuality for different reasons or have differing relationships with the concept. John needs to satiate his masculine urges, Cynthia uses it to gain favor and to manipulate others, Ann is afraid of intimacy, and Graham, more than anyone else, uses the sexuality of others for his own gain. Graham is a bilateral voyeur. He is an active viewer of the sexuality of others, putting them in positions whereby they can discuss their deepest desires in a way that is probing but still relatively harmless. He is also a passive viewer of the lives of others, inserting himself into their pasts, presents, and futures by simply being a part of their lives. He delves deeply into their minds, examining their psychological states and deriving pleasure from it. Graham is a perverted character, and sex, lies, and videotape is a film that challenges the boundaries between decency and perversity. However, the perversion isn’t necessarily related to sex – Graham is a character that lacks morals, not because of his preoccupation with hearing narratives of sexual experiences, but because of his ability to exploit these women psychologically, manipulating them into becoming vulnerable and helpless to his perverted gaze. sex, lies, and videotape is an uncomfortable film to watch because its representation of desire, particularly from the standpoint of Graham, creates a sense of unsettling discomfort that is stark, uneasy and often unbearably fascinating.

The most interesting statement made by sex, lies, and videotape is that it has made analogies to the filmmaking process itself. In some ways, sex, lies, and videotape is a very metafictional film, focusing on the fact that by watching this film, the audience itself is a voyeur, privy to the inner insecurities and turmoils of ordinary people. sex, lies, and videotape may have a sexual undertone running through it, but the real perversion comes from the fact that the audience is gazing at the sordid lives of ordinary people, attending their daily trials and tribulations without being an active part of their lives. Much in the same way Graham views these women from a distance, interacting with these from afar, the audience is given access to the affairs of these characters without becoming involved. This aspect of sex, lies, and videotape is one of the more admirable, an intense and explicit examination of the human condition, complex and without much remorse for what is presented. In many ways, sex, lies, and videotape is a statement on the perverse nature of cinema, and Soderbergh uses metafictional implications well, never overtly stating it as his intention, but it becomes clear that there is far more here than simply being a film about sexual desire – its about the perverse attraction we have to the lives of others and considering we are living in the era of heightened social media and radically popular reality television shows, sex, lies, and videotape is as terrifyingly relevant today as it was in 1989.

sex, lies, and videotape is an unusual film, and if there is one aspect of it that can be considered an enormous merit, it is the fact that it is a film that is completely unpredictable. The direction this film is going to take is entirely unclear, and the result is a strange but unique and subversive portrayal of common themes, shown in a way that is unexpectedly complex and brilliantly constructed. It is an explosive debut for Soderbergh, and while it is flawed in many ways, it does have some interesting statements to make, and the film as a whole is quite successful in conveying the existential desire felt by ordinary people, who are seduced by the private lives of other people, gazing like perpetual voyeurs without actually becoming involved in any way. The cast is dedicated, the story is odd but undeniably fascinating, and the film as a whole is polarizing and volatile, but it all works towards making sex, lies, and videotape quite an experience. I am not entirely sure what Soderbergh was trying to achieve with this film, but he certainly did it boldly.

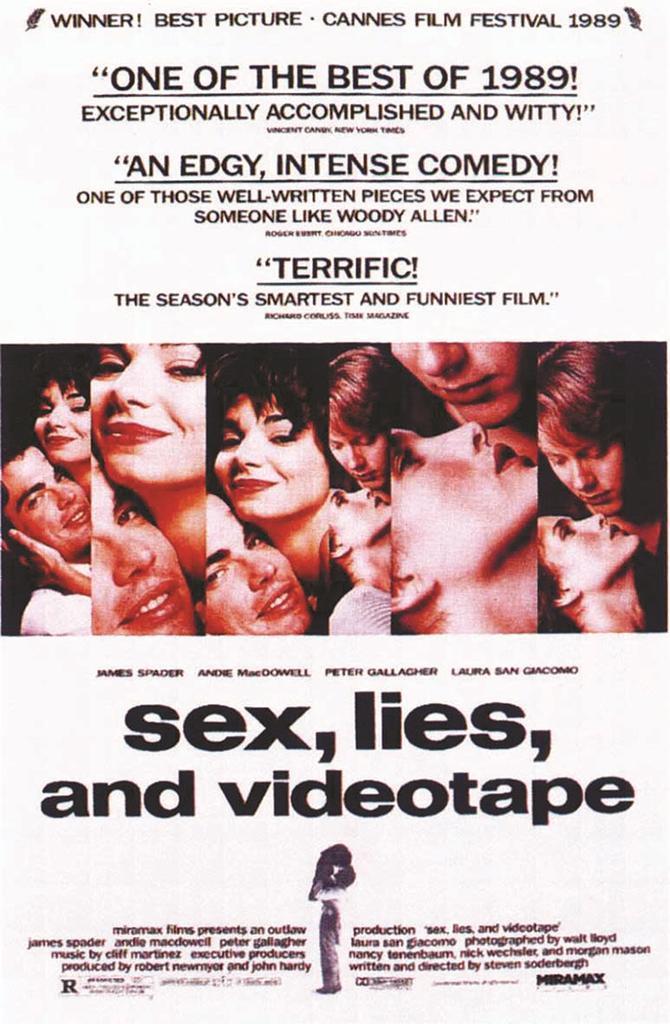

In 1989, sex, lies and videotape was nothing short of revolutionary.

The film won the Audience Award and is credited with bringing the Sundance Film Festival to the forefront of American filmmaking. The movie was purchased by Miramax, and its innovative marketing gave substance to the fledging company and status to a new Hollywood mogul named Harvey Weinstein. The film won the Palme d’Or at Cannes and Best Feature Film at the Independent Spirit Awards. The thrill of a simple movie about ideas shot on videotape empowered struggling filmmakers and fed the belief that the studio system was dying. No surprise that the Oscars failed to embrace the independent film fave. The fantasy was that anyone could be Steven Soderbergh, write a screenplay in eight days and shoot it in four weeks on a miniscule budget.

All of that was thrilling, but it was the content of sex, lies and videotape that riveted its young urban audience. Graham (well played by James Spader) is an intriguing hero. He is impotent. Sexual gratification comes from listening to women. Men weren’t listening to women in late ’80s. They certainly weren’t engaged in understanding a woman’s attitudes toward her sexuality. Graham has stacks of videotape where he listens. Women, even repressed women like Ann, leap at the opportunity to be heard. The idea was startling. There is no physical nudity in sex, lies and videotape. Rather, it is the raw emotion bared that seduces the viewer.

Look at the opening sequence. As we watch Graham traveling to visit his college buddy John and wife Ann, we listen to Ann talk to her therapist about her life. As we learn she is stalled emotionally, dissatisfied, the camera makes clear that Graham is moving toward her. Something will change. Sound becomes key to the artistic success of the film. Audiences were long familiar with Robert Altman’s trademark over lapping dialogue. Soderbergh takes the concept to a new dimension. Sound from the previous scene would continue in the next. Voices from the next shot were heard early, sometimes a remarkable length of time before the visual moved forward. The manipulation of sound created a sense that there was no longer a sense of true privacy. It fed this gnawing nugget of awareness that technical advances were invading our most intimate moments. We may not be exhibitionists, at least not intentionally. Intimacy was changing. sex, lies and videotape didn’t provide answers but rather provoked conversation.