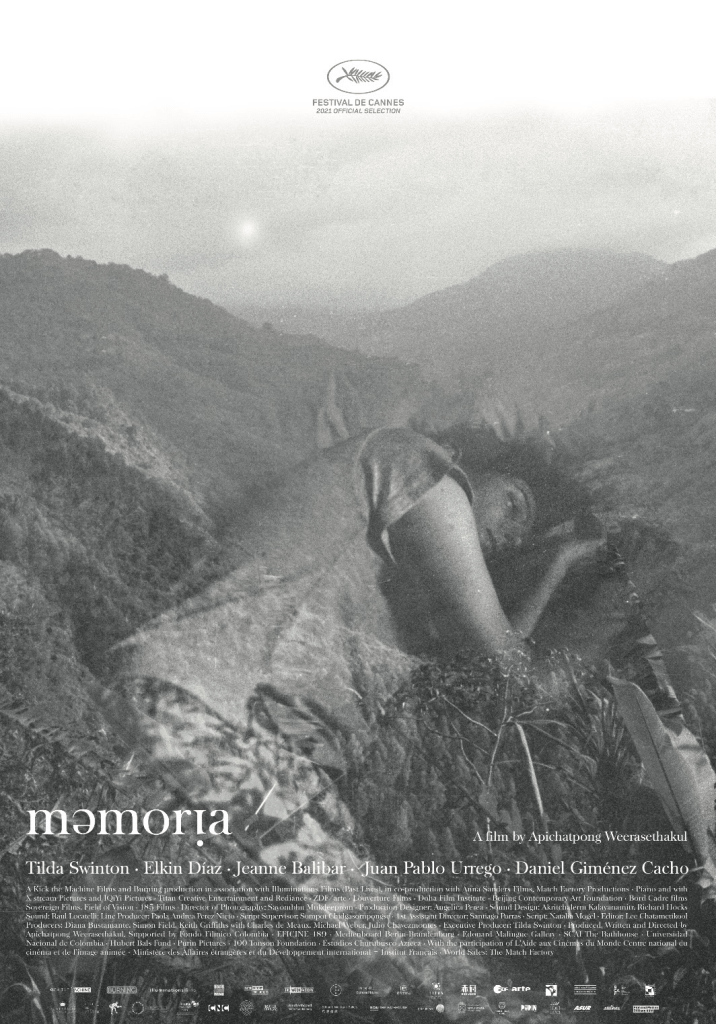

Few names evoke the sensation of absolute prestige and artistic brilliance more than Apichatpong Weerasethakul, who may have only made a few films over his career, but each one is a perfectly-crafted masterpiece of existential complexity. His most recent offering is Memoria, in which he collaborates with Tilda Swinton in telling the story of a British biologist who finds herself questioning reality and everything associated with it while visiting the Colombian countryside after her sister is diagnosed with a mysterious disease, which occurs concurrently to our protagonist starting to hear a mysterious sound that begins to haunt her, driving her slowly into a spiral of existential dread, forcing her to seek answers anywhere she is able to find them, only for her to learn that one simply doesn’t set out to resolve issues that relate less to the tangible world, and more one’s inner psychological state. Going from a bustling metropolis to the tranquility of the pastoral recesses of the country, we follow her as she uncovers clues that relate to her growing sense of unease, which prove to stem not from the outside world, but rather (as she slowly begins to suspect) her internal life, where the various quandaries and questions that have bothered her for an unknown amount of time start to manifest as an unsettling sonic boom that hints at her deep insecurities and restless soul, which she endeavours to fully comprehend through voyaging into the most abstract parts of her mind. Yet, as opaque as this description may be, it is the only way to begin to explain Memoria, a film that was not created with the intention of making sense, but rather evoking various sensations in the viewer, who will undoubtedly find themselves questioning their own mortality and understanding of reality after experiencing the world as filtered through the eyes of one of contemporary cinema’s most enigmatic but brilliant masters.

Memoria is a film composed less of a coherent story, and more from fragments of life, which serve as clues for the main character’s perpetual search for meaning – and much like the celebrated director’s previous work, the film carries with it a deep sense of philosophical ponderings, which don’t always evoke the kind of pleasure in the viewer as more conventional films normally would. However, this is to be entirely expected – Weerasethakul has always been a filmmaker with a keen interest in transcending everything that is supposedly sacred about cinema. His films refute the fact that a traditional narrative structure is required, and replaces it with a more peculiar method of storytelling, one that is based on visceral reactions caused by sensory stimulation, rather than anything that can be fully comprehended in words. Memoria fits in perfectly with his other work, despite being produced outside his native Thailand, in languages foreign to his own – and any artist who is able to venture out of their comfort zone (whether geographically or linguistically) and still produce a work as complex and layered as this warrants our attention. The film is a wildly compelling piece that works best as a series of intricately-woven moments in the life of a woman who isn’t sure where in the world she actually belongs. She is caught between countries, being both an outsider by virtue of the language barrier she continues to attempt to overcome, but still being accepted into society through engaging with the fundamental culture that drives her environment. Memoria is as much a film about the character of Jessica Holland as it is about Colombia itself, and Weerasethakul captures the grandeur of the country, which is rarely represented in film outside of those produced by its artists, carefully piecing together a beautifully poetic version of the world, as seen through the perspective of an outsider attempting to portray the endless mysteries and small beauties of a nation and culture preserved in a very particular moment in time.

Whether Memoria is set in the past, present or future is entirely up to the viewer’s individual interpretation – logically, based on the landscape we encounter at first, we’re led to believe that it is set during the modern era. However, as the film progresses, we start to question even the most fundamental facts around its setting, inching closer to the director’s proactive vision of reality through the eyes of someone who is enduring some form of psychological unease, whether it be regrets for the past or the uncertainty of the future, both of which are challenging concepts to fully unpack, let alone in a single film. Memoria finds Weerasethakul exploring themes centred around the inexplicable burden of the past – the character of Jessica finds herself plunged into existential despair when she encounters a sound that not only keeps her awake at night, but forces her out of whatever version of reality that sustained her up until that point. She starts to find patterns in her everyday life, this sonic boom forcing her to reconsider all the details, which only further motivates her to plumb each moment for meaning. The ultimate resolution (if we can refer to the conclusion of this film as such) is that we are all inextricably bonded – not only those who exist alongside us at the present moment, but those who have passed through this world already, and those who are yet to emerge. However, what bonds us isn’t our shared humanity or the fact that we populate the same world (an idea that the final moments of the film bring into question in one of the most spellbinding moments of the year), but rather the collective memories, both individual and collective. Memoria is quite simply a film that voyages into the past, present and future, presents them as a singular homogenous entity that occurs simultaneously, and is supposedly neverending, at least not in terms that we have been able to understand, which gives the story even more nuance, since it proves that there isn’t really much need for the details we encounter to make much logical sense, since they’re ultimately part of a much broader discussion that Weerasethakul is facilitating throughout the narrative.

Memoria was crafted by a number of people from across the globe, but beyond Weerasethakul and his authorial voice, the other most important creative force behind the film is Tilda Swinton, whose performance as the main character is undeniably among her best work. Considering her ability to be something of a chameleon, which has allowed her to adapt to a range of styles and take on absolutely any role, Memoria presented her with a few more challenges than normal, mainly considering how Weerasethakul’s films aren’t particularly known to be acting showcases. Throughout this film, we’re reminded of why Swinton has led such a flourishing secondary career as a model – not only is her otherworldly beauty so striking, she has the ability to convey the deepest emotions through her expressions and movements. This film is one where the words are secondary – there are long passages of dialogue between characters (and the discussions are suitably fascinating), but they are drowned out by the grandeur of the people delivering these lines, with Swinton in particular calibrating her performance to be one that is carefully measured alongside the narrative, doing exactly what was expected from her, without trying to dominate the film, despite it being almost entirely centred on her character. This comes from the fact that she is willing to surrender to being merely a human vessel for the director’s ruminations on a range of themes, rather than being the most important aspect to the film. This isn’t to imply that Swinton is expendable – she is one of the few performers working in film today that realizes that acting isn’t always about standing out, but rather blending in from time to time – and throughout Memoria, we see the actor take the opportunity to become yet another aspect of Weerasethakul’s gorgeous landscapes, just one of the many components of his stunningly beautiful existential tableaux that tell more from a single shot than most films manage to do through entire segments.

Considering how Swinton (and the rest of the actors, which include a multi-national group of individuals such as Jeanne Balibar and Daniel Giménez Cacho) are merely narrative elements used by Weerasethakul in the creation of this film, the primary propellant of Memoria is actually the aural landscape. The work done to bring this film to life through auditory stimulation should not be understated – there is a reason why there has been such an emphasis on keeping Memoria as a theatrical experience, since the director (who is known to push a few boundaries with every one of his films) understands that a film is more than just a strong script and stunning visuals, and that sound can tell a story just as well as words can. The various sounds we hear throughout the film paint a vivid picture of the world we live in – music is kept to a minimum, with the majority of the atmosphere being constructed from everyday sounds, which gradually begin to drown out the outside world the more the viewer ventures into the film. This not only has narrative influence (particularly in how these sounds begin to take on the same function as tangible words, with the character of Jessica seemingly being in perpetual conversation with her environment, whether it be in the bustling cities she calls home, or the distant countryside in which she finds the answers to the questions that have been puzzling her), but it strengthens the impact the film ultimately has when it comes to conveying its central themes, whatever our individual interpretations surmise it could be. Sound is often disregarded as an essential component of the film, but throughout Memoria, the director proves how vital it can be in telling a story and establishing an atmosphere, centring our emotional attachment around how we engage with these small but pivotal auditory cues that ultimately converge into this stunning existential drama.

Memoria is a strange curio of a film – at first, it seems like a very artistically-driven story that focuses less on the events, and more on the sensations that occur in between them, but rarely are subjected to much overt exploration. However, as the film progresses, we see that (while this is true), it is far more complex than just an attempt to look behind the psychology of a woman carrying the weight of the past, but rather a more direct voyage into the human spirit, taken from the perspective of someone who could resemble any one of us, the character of Jessica being ambiguous enough for anyone to form a resonant connection with her. There are many questions asked by Weerasethakul throughout the film, and none of them are answered, at least not explicitly. Instead, the only resolution we get comes in the form of the gradual emotional catharsis that we feel alongside the main character, who ends the film by sitting in silence, overcome by emotion and overwhelmed by the realization that time is fleeting, and that life is not a linear series of moments, but rather a continuous stream of experiences that find the past, present and future blurring together, from which we are given the opportunity to make our own conclusions. It is inherently difficult to talk about Memoria, since it is not a film that lends itself to a singular conversation, but rather evokes a dialogue, which is exactly the response that a film like this should aspire towards. It’s beautifully poetic and incredibly moving, and while it takes its time, moving at a deliberately measured pace, not a single moment is uninteresting. Perhaps to fully comprehend the scope of this film and its message, we can look at the final act, which is dedicated to the character finally succumbing to the realization that existence is not as easy to comprehend as we initially believe it to be – when confronted with understanding the world, she makes the startling discovery that time simply does not exist, being an unnatural construction that simply is used to compartmentalize the endless stream of consciousness we call life.