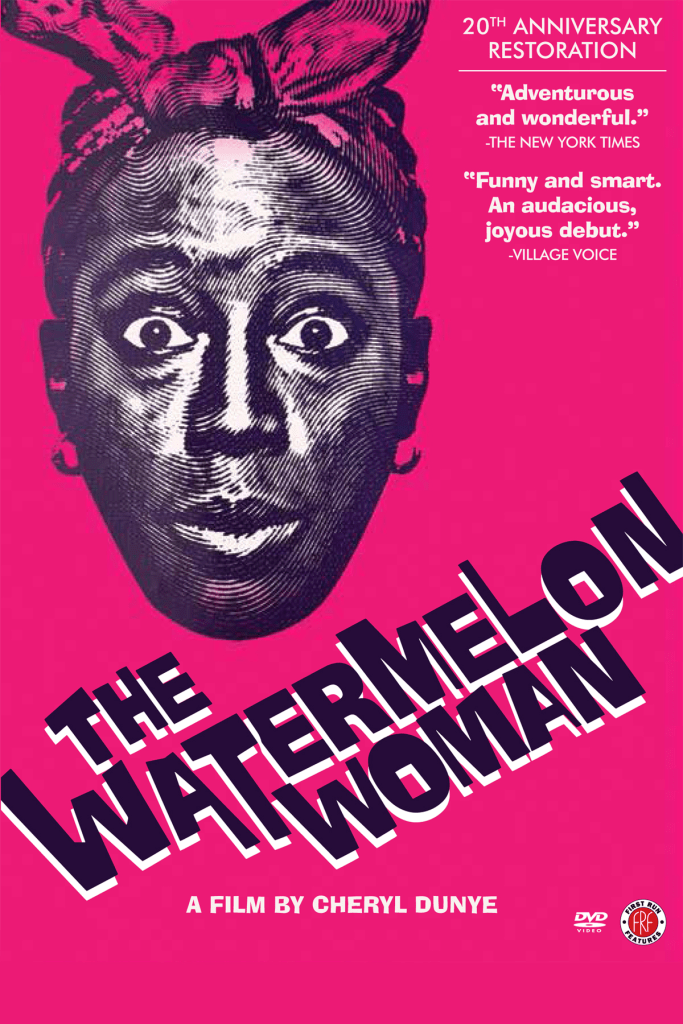

When Cheryl Dunye set out to make her first feature-length film after a few years of short-format filmmaking, she had quite a challenge ahead of her, not only because she was a relatively novice director, but also because there were simply very few people like her making films, even in the independent sphere. However, these were not limitations, but rather the precise kind of obstacles that fuelled her to take such a risk in the first place, since it provided the urgency necessary to propel a young artist. As the post-script to the film mentions, in order to have your stories told, sometimes you need to do it yourself – and considering Dunye was a young filmmaker whose identity reflected three groups that were heavily marginalized in cinema at the time when it came to the people whose films were financed and distributed widely (being an African-American, a woman and a lesbian), she was certainly not someone who had an easy journey to get her work produced and seen by a larger audience. Yet, she defied the odds, and the fruits of her labour resulted in The Watermelon Woman, quite simply one of the most important films of the era. Produced at a time when people like Dunye normally found themselves either sidelined and forced into making films that were more accessible according to the supposed interests of viewers, or ignored entirely, kept safely concealed behind layers of obscurity, recognized only by those who dedicate their time to exploring the hidden recesses of the industry. This was not enough for Dunye, who bursts into the world of independent cinema and added a necessary boost of inclusion to a cinematic landscape that was welcoming new voices en masse, so much that even at its most subtle, the film is a remarkable achievement that forces us to pay attention and marvel at its unrestricted and genuine brilliance.

Independent cinema has served many functions, but the two that are most prominent is that it gave a start to many young and rambunctious filmmakers looking for their entry-point into the medium, as well as allowing those from different backgrounds (including those previously marginalized under the quite myopic studio system) to have access to a small but worthwhile set of resources that allowed them to have their stories told. Dunye represents both groups, and crafted The Watermelon Woman a film that quite literally changed the way cinema was made, not only because of the story it told, but the people who were involved in its creation. It may sound like hyperbole, but this film is one of the most important pieces of queer media ever produced. Created almost exclusively by queer women of colour, including Dunye (who is involved at every level of the film’s production, from playing the lead role to the editing process), the film represents a watershed moment for inclusivity, which opened the doors for so many other filmmakers to have their work financed. Independent cinema is normally associated with shoestring budgets and raw, unfiltered filmmaking that conceals incredible talent, but we rarely discuss how this was not a genre at first, but rather a movement that thrived on diversity, being pioneered by artists who did not fit into the mould of what a major Hollywood director supposedly should be. Dunye embodies this fierce independence in its purest form, and every frame of The Watermelon Woman demonstrates her incredible dedication to making way for future filmmakers like her – not too many artists can genuinely be considered trailblazers in the literal sense, but she certainly is a strong example of someone who earns every bit of that reputation.

What is important to remember about The Watermelon Woman is that this is a film that is built on multiple layers. The forthright queerness is clear and integral to the narrative, but it’s not the only source of discussion that we find in the film. As much as she is a social activist and someone dedicated to forging a way for young artists from the LGBTQIA+ community, Dunye is also someone who genuinely adores cinema, with this film being her tribute to the medium, filtered through a series of discussions around the role of black women in the earliest years of Hollywood, since they were amongst the most invisible contributors to this supposed Golden Age of filmmaking. The film presents itself as somewhere between a narrative feature and a documentary – we know that the story of Fae Richards, or “The Watermelon Woman”, as she was credited in her roles, is fictional, a construction of the director who uses the titular character as an entry-point into her deep and insightful conversation of the role black women played in Hollywood history, since they had the misfortune of being omnipresent in many of these films by virtue of playing small roles, but being shoehorned into specific roles that were explicit in perpetuating racist stereotypes, thus rendering them as not only invisible in terms of their contributions to the industry, but faced with the challenge of having to work even harder than others to shed such an image. It’s a fascinating portrait of cinema and its history, done as a series of images and conversations by someone whose identity inherently put her on the outskirts of the industry at the time – and we simply can’t resist the immense impact the film has when it hits its stride and manages some profound commentary.

The Watermelon Woman brings up many important topics on the subject of the film industry and its treatment of minorities and marginalized groups – but it’s not only the message it is conveying, but also the form the film takes. This film has dual purposes – firstly, it acts as Dunye’s scathing but poignant indictment of the film industry, making it a work that acknowledges the state of the medium in both the past and present forms. However, it is also her demonstration of what she believes the future of cinema could be – ultimately, as much as The Watermelon Woman is about questioning the shortcomings of Hollywood in terms of how it treated marginalized groups, it is still a film that is intent on showing what can be possible when someone from outside the supposed status quo is given the platform. In between conversations on the history of cinema, there are two additional components that make up this film – there’s a beautiful romantic sub-plot between the main character and her newly-found lover, as well as a very unconventional buddy comedy between Dunye’s character and her work colleagues, which makes The Watermelon Woman a film that is working with a lot of different subject matter. For this to be Dunye’s debut is absolutely astonishing – she proves her mettle as a director with not only a clear vision in terms of how she comments on the more important issues, but also one with an eye for both comedy and romance, which are seamlessly interwoven into the film, allowing The Watermelon Woman to be much more than it may seem to be at our first glance. In the same way that the cultural discussion provokes thought, the romance makes us swoon and the comedy incites raucous laughter, allowing the film to not only be a great piece of metafictional cinema, but simply a solid work of inclusive film as a whole, one that goes above and beyond the limited scope of similar stories.

However, as much as we would like to attribute everything about The Watermelon Woman to its status as one of the greatest films on the subject of cinema itself, what really allows it to stand out amongst a wealth of other similar films is how fiercely independent it is, in both spirit and technique. Few filmmakers have ever benefitted from the trust of their producers more than Dunye, who utilizes the freedom afforded to her as an independent filmmaker to tell a story that was unabashedly and proudly queer, years before the media started to focus its attention on telling these stories. Dunye has never been someone whose interests have been to just make a film and allow it to flourish on its own – she stands in firm resistance to the idea that a filmmaker’s sole responsibility is to create the work and allow the audience to keep it alive. Every moment in The Watermelon Woman simmers with the kind of steadfast intensity that makes it such a truly electrifying work, handcrafted by someone who has the most undying devotion to the material, so much that she seems to be relishing in the ambiguity between fact and fiction, having to outright state that (despite how realistic its reconstructions of the titular character’s life may be), that everything contained in the film was a fabrication. She knows how to draw on the ambiguity that comes when addressing very real issues through a fictional lens, and it allows her the time and space to make some profoundly complex statements on the nature of the industry, which is tied together with a caustic but warm sense of humour that makes The Watermelon Woman such an endearing but complex work, and one that accomplishes all of its goals, to the point of filling some of the vague spaces with genuinely entertaining content that allow it to be simultaneously a great meditation on the film industry, and a wonderfully charming comedy.

One of the first facts one learns about The Watermelon Woman is that this is the first feature film ever directed by a black lesbian – and while this may be up for debate (since we cannot possibly have the comprehensive history of every film and the identity of its creators to make such a bold statement), it is the piece of trivia that has kept the film afloat, even if only superficially, since actually watching the film proves that it is much more than just an interesting entry into the world of independent cinema. This film is not only a great piece of storytelling, but a forthright act of rebellion in its own way – to have a black, queer artist put herself in a position like this, where her vision is the sole propellant of a film like this, was a daring move. Perhaps we have evolved to the point where this is a lot more common, but for a film produced a quarter of a century ago, it was quite an achievement, and something that should be celebrated as a massive step forward in terms of inclusivity in an industry that is still striving to give a voice to those who have been historically sidelined by heteronormative standards. The film offers a lot, but it also isn’t afraid to make good use of the resources afforded to it, which was significant all on its own, since it is unlikely that a film with this subject matter (which is still considered quite provocative, and would have certainly been seen as incendiary in previous decades) and made by someone like Dunye, would have been given any attention, or even the chance to be funded in the first place. It’s not often that we find a film that feels like it is truly historically significant all on its own, but The Watermelon Woman is one of the most notable examples, and a film that feels like nothing short of a true revelation. Whether we find the cultural commentary on the history of film fascinating, or the romantic comedy elements endearing, there is always something of value on screen throughout this film, which is a distinctive and important moment in the history of independent film, and a beautiful entry into the industry that it is so fervently critiquing and deconstructing, leading to a work of immense artistic and socio-cultural resonance.