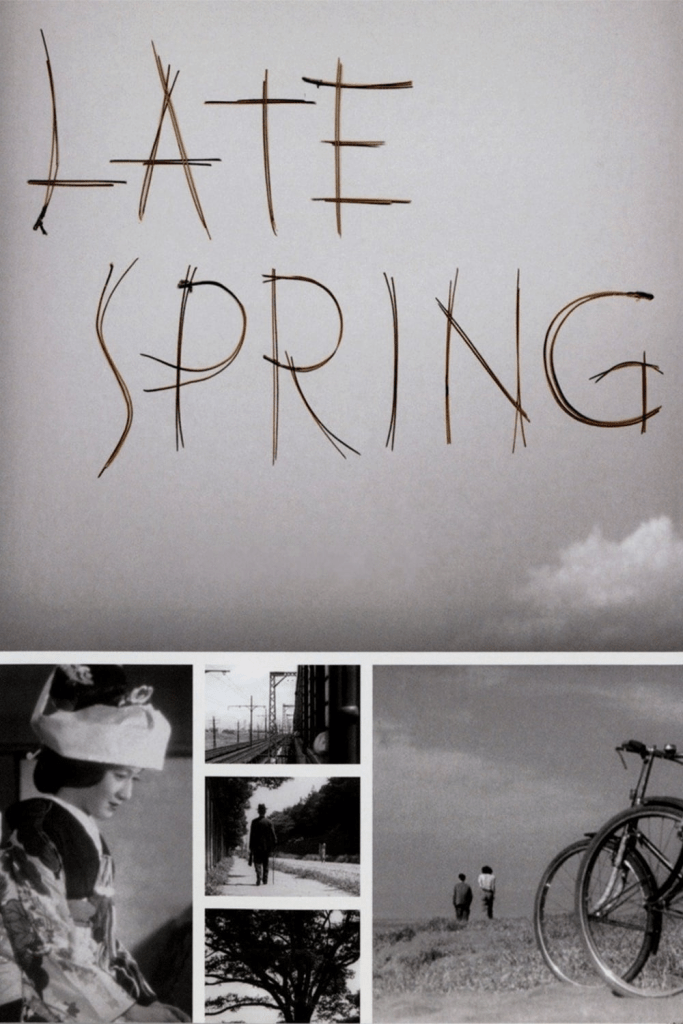

As arguably Japan’s foremost cultural critic, few filmmakers managed to as effectively explore the life and times of ordinary citizens quite as well as Yasujirō Ozu, whose work reflects a keen sense of interest in the human condition, which has fuelled so many of his incredible films. As is often the case with notoriously prolific directors who produce work over a long period of time, Ozu’s work can be divided into various eras, each one defined by both the socio-cultural milieux that surrounded them, and the director’s varying methods of infusing these ideas into his films, many of which would come to be definitive of their particular period, not only in his career, but in the history of cinema as a while. Late Spring (Japanese: 晩春) signalled the beginning of a new stage for the director, one that some consider to be his longest and most important, others seeing it as the penultimate era before Ozu would begin working in colour, which he would utilize until his passing over a decade later. Regardless of how one categorizes it, Late Spring is an absolute triumph, being a beautifully complex story of human desire and the insatiable feeling of loneliness that encompasses many of us on certain occasions. There are numerous themes woven together in the formation of this film, which functions as a strikingly beautiful character study that touche son issues of identity and isolation in a way that only someone as fully in command of their craft like Ozu could achieve, since every scene continues to build to an absolutely striking climax that is both melancholy and joyful, which is everything we could hope for from a director who consistently demonstrated exactly how he had mastered the art of humanity-fueled storytelling.

We have previously spoken about his work on numerous occasions, and something that becomes increasingly clear with each new story is how there is a cumulative power of his films, each one building up on the others to form a varied and multilayered tapestry of Japanese society throughout the central years of the 20th century. Each film is a fragment of a larger socio-cultural document, which (when perceived all together) creates an unforgettable galaxy of stories, each one simple and intimate, but hinting at something much deeper. On a personal note, my journey with Ozu has been one defined by patiently waiting to see where these stories lead – they may seem quiet in isolation, but when you start to place them in contrast with one another, paying attention to the intersections of certain themes (some more explicit than others), there are unmistakable rumblings of profoundly powerful social commentary. Ozu’s modus operandi is not to make films that cover several themes, knowing that he’d always have the opportunity to expand on certain ideas that are not essential to the present project in the future, which he nearly always did. He wasn’t someone who put too much value into creating works that were designed solely to be multidimensional critiques of several areas, and instead was far more invested in individual ideas. Here, we see the recurring theme of a man who knows his time is limited, frantically searching for a suitable husband for his daughter, who claims that she is perfectly happy to be her father’s caretaker, but who he knows is secretly extremely lonely. Concepts surrounding arranged marriage and the role of women in postwar Japan are all explored throughout Late Spring, which exists as a powerful and often quite potent glimpse into everyday life, as was Ozu’s speciality.

As a character-driven piece, Late Spring places an enormous amount of emphasis on the actors tasked with bringing these individuals to life. We’ve remarked in the past about how, despite not having an enormous amount of name recognition outside his native Japan, Chishū Ryū is quite possibly Ozu’s greatest collaborator, appearing in all but two of his films, making him a solid bet for any of the director’s works, whether it be in the leading role, or playing a scene-stealing supporting character that we’re pleased to see appear, even if only for a short time. Late Spring is one of his best performances, with his portrayal of the widower trying to help his daughter establish a future being one that simmers with dedication and earnest compassion, something we encountered often when it came to his performances. However, as terrific as Ryū may have been in the film, Late Spring belongs wholeheartedly to Setsuko Hara – already something of an established actress as a result of a few years of excellent work, her first foray into Ozu’s orbit is one that stands as one of her best. As one of the most extraordinarily expressive actresses to ever work in the medium, Hara was able to say more with her movements than any words possibly could, and the part of Noriko, a young woman motivated by her familial duties, but impaired by a crushing sense of loneliness, she is able to take on a role that plays specifically to her brand of emotive acting, where she manages to convey every feeling contained in this character’s mind, without allowing it to become hysterical or over-the-top. Hara was an unquestionably gifted performer, and Ozu truly managed to give her one of her best roles – and considering this was their first time working together, it feels almost serendipitous, since they’d go on to collaborate on several more occasions in the future, each one just as effective as this film.

Many consider Late Spring to be amongst Ozu’s best work, and once we’re fully enveloped in the beautiful and poetic world he evokes, it’s certainly extremely difficult to argue with such a sentiment, especially when we start to feel those familiar sensations of human empathy that excude off every frame of the film. There is an extraordinary quality to this film, one that comes about through Ozu’s steadfast appreciation of the small details. His work rarely came across as hysterical or excessive, with his style being more focused on the more simple sides of life, which reflects the conventions of the shomin-geki sub-genre, which offered insights into the lives of ordinary people, much in the same way as British kitchen-sink realism or Italian neo-realism would in later years (while being much less propelled by political issues, instead being more socially-resonant). Despite being made over seven decades ago, every moment of this film feels entirely genuine, and Ozu places us in the world of these characters, so much that we feel entirely present in each scene, passive observers to the daily activities of these characters, who may not be particularly exciting in theory. but are developed with such authenticity, it can sometimes even feel somewhat misplaced that this is a fictional film. Far from the simple slice-of-life drama detractors often associate with the director, Ozu approaches his films from a place of detailed, intricate storytelling – and while it may not be to the taste of absolutely everyone who may come across it, for those who are attuned to the director’s style and particular artistic curiosities, there are few of his films more poignant than this one.

As one of the director’s most challenging works, Late Spring is a fascinating deconstruction of a range of common themes that are repurposed to be absolutely gorgeous and heartwrenching under the careful direction of a filmmaker whose extraordinary compassion for the human condition is entirely unmatched. Beautifully poetic and often quite funny (carrying that distinctly gentle wit that is present in even the most downbeat of Ozu’s films) – and there is a legitimate argument to be made towards this being amongst his finest films, if not his very best overall, especially since it exists as a perfect companion piece to Tokyo Story, which touched on similar issues, albeit from a very different perspective. Yet, like anyone who is at all accustomed to the director’s work will undoubtedly understand, it’s not enough to simply understand the story, we have to enjoy the experience. This is an evocative, beautifully poetic story of a father and daughter, and their shifting relationship as they both stand on the precipice of major changes. It’s simple and delicate, and has an abundance of heart, most of which is channelled through these extraordinary performances given by the two leads, as well as the memorable supporting cast, all of whom are extremely good and add to the unique perspective offered by the film. Late Spring is a delicate and meaningful human drama, and a fervent reminder that Ozu was undeniably one of the most important filmmakers of any generation, and whose work continues to reverberate with the intensity and heartfulness that it did when it was first seen by audiences decades ago.