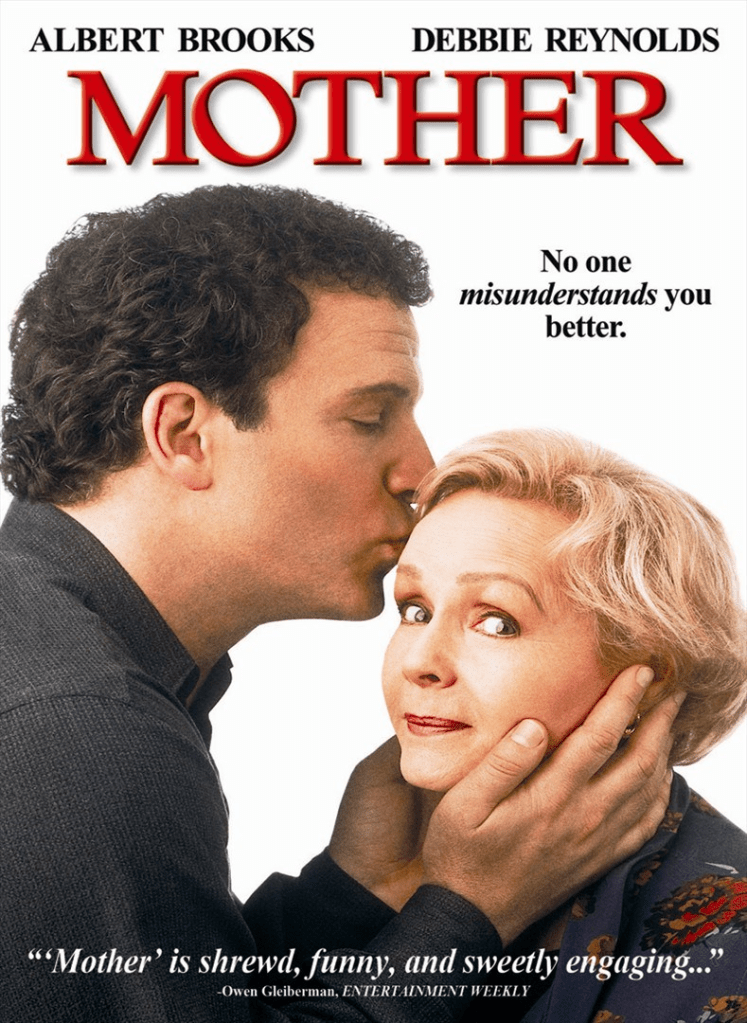

As unheralded as a filmmaker as he may be, Albert Brooks certainly has quite a knack for telling stories that resonate with many viewers, in a way that is accessible and endearing, rather than being contrite in the way many mainstream comedies tend to be. A populist filmmaker, but one that uses his platform in creative ways, Brooks pushed a few boundaries without ever becoming all that complex in the stories he told. Mother is one of his more cherished works, for a number of reasons – it has that same sweetly sentimental but wildly funny tone that Brooks perfected on both sides of the camera, a very strong message that has its roots deep within humanity, and (perhaps most of all), a major return to the screen for one of Hollywood’s most incredible performers, who took on her first leading role in nearly three decades when she signed up to play the titular character. Mother is a wonderful film – it may have been made during a decade where the director was aiming more for entertainment rather than concept (which propelled his work in the 1980s), but as far as gentle but hilarious comedies that find the warmth in every situation go, it achieves everything we’d expect from a film of its ilk. Memories surrounding this film are positive, and it remains one of Brooks’ most established and interesting works – and the fact that he made something so meaningful without having to abandon the style that made him such an interesting writer and director in the first place, is even more impressive, considering that there were so many opportunities for Mother to be derailed by unneeded ambition or the low-hanging fruit that was readily available to it. From all angles, this film is a wonderful piece of charming comedy, and just an absolute delight from beginning to end.

It’s well documented that Brooks always intended to have the role of Beatrice, or “Mother”, occupied by a legendary actress, and he certainly ran the gamut in finding an appropriate person for the part, which eventually led him to Debbie Reynolds, whose performance in this film is absolute perfection. She may have been out of the spotlight for a while (mainly working in supporting roles, and on television), and was certainly not the young ingenue many remember her as being from her earlier days of stardom – but she’s still as sprightly as ever, the spring in her step and mischievous glint in her eyes still being as present here as they were when she was at the peak of her fame. This role reignited not only Reynolds’ career, starting a new chapter where she could play matriarchs with the same camp sense of style and humour that she possessed as one of the grand dames of 1950s cinema, but also kickstarted a wide-ranging reanalysis of her work – she wasn’t only the striking young actress from a number of major films during the Golden Age of Hollywood, but a gifted comedian and performer that could enchant us with even the most mediocre of material. Her performance here reminds us of that – she may be older, but she’s still just as gifted, and rather than simply being built around her presence (often a quality of these films that seek to have major stars of yesteryear in substantial parts, where simply being in the film was enough), she’s actually giving a dedicated performance, playing Beatrice with a combination of wise-cracking humour and deep, emotional pathos. She’s so wonderful, not even Brooks in his capacity as her co-star, turning in one of his finest performances as a man unravelling into a state of depression, is all that noticeable – which only proves the extent of their chemistry.

I’ve spoken about it at length, but Brooks’ films are always very much focused on a particular topic – he never sets out to prove his endless ambitions with projects that extend over many different subjects. These are multilayered films, but they’re built on a particular thematic foundation. It isn’t difficult to figure out what Mother is about, and Brooks does give the audience the benefit of the doubt in knowing that we can easily extract meaning, allowing him to avoid exposition and cut to the chase. Motherhood (or parenthood in general) is a theme that art has always been focused on exploring – along with love and death, it’s one of the core concepts that most art can be drawn to. There’s something always so compelling about a film focused on the relationship between a mother and her children, regardless of whether it’s a particularly positive view on parenting – and while it’s presumptuous to state that we are captivated by these stories because it reminds us of our own relationship with our parents, the idea of reconnecting with an older maternal figure – whether a relation or not – is rich, fertile ground for interesting conversations. Brooks doesn’t avoid these discussions, but instead filters them through his unique brand of humour – we’d expect a film like Mother to come to a screeching halt and overwhelm us with an abundance of heavy-handed emotions once the inevitable resolution has been found – but while we do get these moments of tenderness, they’re still extremely funny and keeping with the spirit of the film, which is one where the irreverent comedy intermingles with the emotional basis, creating a vivid and distinct portrayal of a unique mother-son dynamic.

Brooks doesn’t say anything especially revelatory in Mother – he keeps it incredibly simple in terms of the narrative, and perhaps even could be considered to be playing it a bit too safe in some instances. However, where the film deviates is in the absolute compassion it shows to its characters, and to the audience by association. Just as much as Mother is an outrageous comedy about a man conducting an experiment to find out the root of his strained relationship with his mother, it is also about two people trying to connect with each other after years of tension – perhaps it’s not particularly vitriolic or abusive in any way (being mostly restricted to passive-aggressive comments, and the occasional invasion of privacy). There is just as much commentary on the character of John in his capacity as the lacklustre son of a woman who just wanted to see her children succeed. There’s a humanity to this film that feels very genuine – neither of the main characters are archetypes, which is a surprising development that we may not have expected at the start, since so much of this film appears to be following the pattern of the entertaining but conventional family-focused comedies of the era. Both protagonists are authentic, and convey earnest emotion, which seems to be part of Brooks’ concerted effort to elevate this film above and beyond simply a derivative, wacky comedy about a mother and her son trying to get reacquainted. It’s a difficult balance to successfully achieve, but Brooks has rarely (if ever) been someone to demonstrate any kind of laziness, whether in his acting, writing or directing – and all three are perfectly encapsulated here in this film.

As a piece of filmmaking, and a work of comedy, Mother is an absolute delight – Brooks has a strong sense of direction, and easily shepherds this charming story to the point where it becomes extremely enjoyable, avoiding all cliches (and when it does veer toward such territory, it becomes something that seems to be actively challenging these conventions). Anchored by a lovable performance the legendary Debbie Reynolds, who is doing some of her finest work ever, constructing a character that is complex, wonderfully unique and always likeable, even at her most eccentric, which contrasts sharply with Brooks, who is playing one of his usual sad-sacks, but in a way that is actually quite insightful and funny. As whole, the film ventures deep into this central relationship, and makes some bold statements that are genuinely quite interesting, while still provoking laughter at a rapid pace. Carefully directed by someone who had a real penchant for constructing comedy that is both funny and meaningful, Mother is a wonderful film, and while it may not be as ambitious as a few of Brooks’ other projects (particularly Defending Your Life, the film he made immediately before this one), but it has an abundance of heart, and an endless supply of well-meaning humour that gives us wonderful insights into the art of motherhood, a subject that has rarely been as outrageously entertaining as it was here.

Mother, to me, is undoubtedly Albert Brooks’s best film. Here he and his co-writer create a flinty widow who isn’t interested in her son’s efforts to explore the depth of their relationship.

As richly complex as the depth Debbie Reynolds brings to the role, she misses that opportunity to ignite a comeback. Reynolds was snubbed by Oscar voters. The film was warmly received but generated only a modest revenue.

Part of the problem in 1996 was timing. As Reynolds was hyped for a return to her earlier glory, Barbra Streisand was creating an identical celebration for Lauren Bacall who finally had a great role as Streisand’s mother in The Mirror Has Two Faces. Bacall was sublime in a role Streisand built for her. Dialogue alluded to her early years as a great beauty. The media fell over themselves to catch a glimpse of Bacall wh9 became the Oscar frontrunner.

Another difficulty for Reynolds was her charm. Beatrice Henderson is meant to be off putting, flinty. After years as a nightclub entertainer, Reynolds is naturally charming. We are supposed to feel reserved about Mrs. Henderson, but Reynolds is so likable that we tend to eye her son John with a raised eyebrow instead.

Reynolds wasn’t the first choice of Albert Brooks. He offered the role to former First Lady Nancy Reagan. The novelty casting feels perfect. Reagan would have that tone to undermine her son’s efforts to bond. Reagan chose to decline the role to care for her ailing husband. Brooks contacted his good friend Carrie Fisher to land Reynolds as a replacement.