We are living in an era where queer stories are not only becoming more widespread, they’re actively emerging as some of the most poignant works in contemporary cinema. One of the fundamental signs that a certain kind of story is starting to be readily embraced by a viewership wider than the niche audience that they supposedly exclusively appeal is through seeing how seamlessly it interweaves with more conventional genres. We’ve seen queer love stories many times before, but these were either restricted to the independent or arthouse corners of cinema, or were produced by and directed towards members outside the community, with only marginal involvement of those from within it. This isn’t to disregard the many valiant efforts that some filmmakers took to have their stories told (as well as those who may not have a personal relationship with such narratives, but at least had the compassion to see that they were worth exploring), but rather to show that we have come a truly long way. Andrew Ahn is one of the most promising young directors working today, and so far he has produced only three films, but each one is a brilliant work that touches on issues relating to the queer community, either explicitly (as is the case with Spa Night) or through vague subtext (with many finding value in a queer reading of Driveways as a film about the process of finding one’s identity early in life). His most recent offering is Fire Island, a more mainstream effort that sees the director take a few steps forward after years of relative obscurity, proving that even when helming a bigger production, he is able to retain the same fierce independence that made him one of the most interesting filmmakers of the current generation, which has seen some fascinating new ideas emerge over time.

Fire Island is Ahn’s boldest film yet in terms of looking at the LGBTQIA+ community, solely on how unabashedly queer it is (making the decision to release it at the outset of Pride Month all the more appropriate), openly celebrating the gay community through a carefully-constructed story of a group of friends venturing onto New York’s notorious Fire Island for their annual week-long sojourn, where they party and make connections that may be meaningless, but feed their desire, whether they are carnal cravings, or simply the need to feel validation from strangers joining them on this queer utopia for a few days of wild behaviour. Contrast this premise with the fact that Ahn and co-writer Joel Kim Booster based the film on Jane Austen’s timeless Pride and Prejudice (which is actively mentioned on a few occasions), and we find ourselves drawn into this hilariously irreverent comedy that draws on a number of themes in an effort to subvert our expectations as to what a romantic comedy should be. Like the classic novel, the film uses romance as a means to comment on social division and class structure, updating it from the lush pastoral estates of England to the gorgeous beaches of the East Coast, which serves to be a worthy replacement, especially since Booster does very well in taking the main ideas of Austen’s novel and assimilating it into this modern version, without being too bound to the original text. More than anything, Fire Island is a fond riff on the novel, rather than an outright adaptation – and using it as a rough guideline, Booster and Ahn venture onto the queer paradise of the title, armed with a strong premise and a forceful conviction to tell a story that is as entertaining as it is vital.

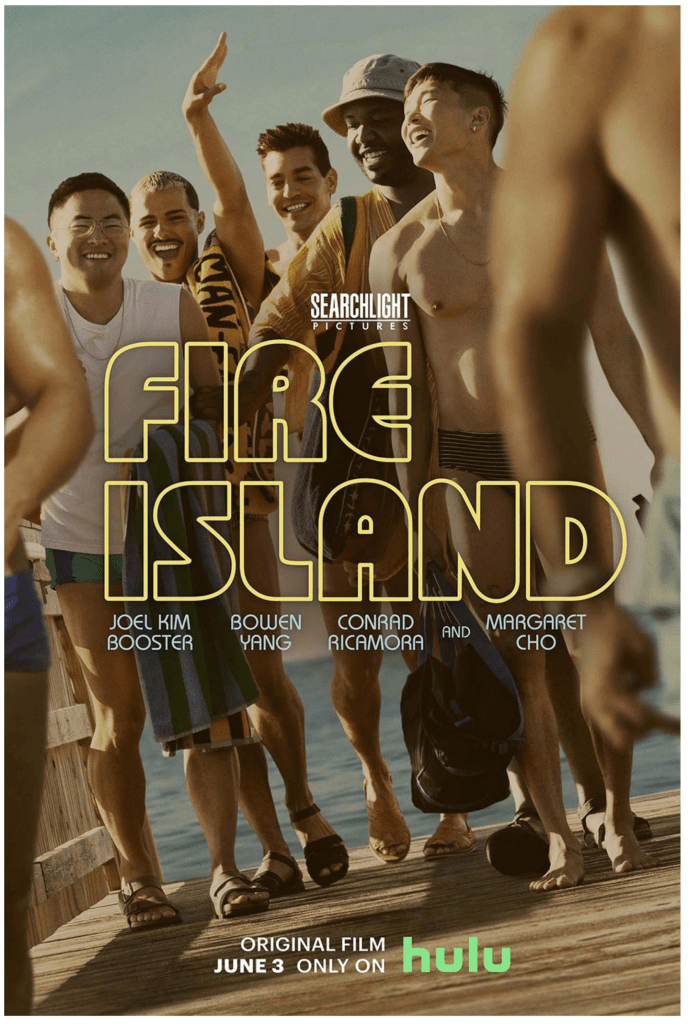

Many actors that come from marginalized or underrepresented groups have tended to express their disdain at the lack of roles, since they’re rarely cast, and when they do manage to make their way into films or television shows, its normally as thin archetypes that don’t showcase the breadth of their talents. It has impelled many to remark that the only way to play roles that they feel warrant their time is to create them, which is exactly what Booster did here. As an actor and comedian who is both queer and a person of colour, his choices for roles have always been limited – so setting himself up behind a keyboard, he wrote Fire Island, which not only served as a vehicle for him as an actor, but also for a cast of queer actors, many of them of colour themselves. You simply can’t play roles that don’t exist, and Booster rectifies this through creating around a dozen unforgettable characters, of which he is one. What is most striking about this film is despite having some incredible comedians in the roles, the emphasis is not solely on their ability to be funny, but also to capture the more dramatic material – in addition to Booster (who proves himself to be an excellent lead), the likes of Bowen Yang, Matt Rogers and Margaret Cho prove that they can command the screen, not solely in terms of inciting laughter, but also in the more quiet moments, of which there are many. At a cursory glance, we may not expect Fire Island to be a particularly actor-based film, but when the cast is as committed to bringing a level of nuance to these roles, it is difficult to argue with its success.

Fire Island is the kind of film that is made when a studio chooses to facilitate some truly exciting queer voices, giving them a platform to tell their story in a way that is safe but not obscured by the belief that audiences aren’t receptive to these kinds of stories. Too much queer-themed cinema has been subjected to the bizarre belief that those aligned with the heteronormative side of the culture will not be able to embrace such a film. Something that this film does particularly well (as well as several other queer films) is that it outright makes it clear that this is not a film primarily directed towards those outside the community it represents. It is certainly entertaining enough to be accessible, but it’s main demographic are the very people whose experiences are shown on screen, and while this may be a very small fraction of the audience (in terms of young queer people with the resources and ability to visit this coastal paradise), there is still an element of resonance in how the director and his collaborators make it clear that this is a film made for the gay community before anyone else. As selfish as this may sound, it is a logical response, considering how the romantic comedy genre has been overwhelmingly dominated by heteronormativity – propelled by the genuine and earned belief that those in the gay community are just as worthy of having a romantic comedy targetted towards them (especially one in which it doesn’t feel as if their relationship is being the subject of endless scrutiny by gawking outsiders), the film is a welcome departure from many queer-oriented films, where relationships are seen as out of the ordinary and trivialized to the point of hinting at the constant desires for those that don’t adhere to the status quo are viewed as the “other”, which this film actively aims to subvert.

However, this all makes Fire Island out to be a much more serious film than it actually is – logically, considering his interest in exploring identity (especially within the Asian-American community), Ahn was always going to bring a level of complexity to the film, but not in a way that distracts from the fact that this is an extraordinarily entertaining film. From beginning to end, it is made with a kind of precise, forthright joyfulness that persists throughout the film, reflecting the fact that, as much as it is a film about some deep issues relating to the queer community (including discussions on the long path towards liberation, and the reasons behind the outward celebration of gay pride that the film orbits around), this is also a wildly entertaining romantic comedy, with all the same tricks that we see in most stories about individuals falling in love. This is where Fire Island does veer towards being conventional, since Booster does ultimately follow the three-act structure that has had a stranglehold over the genre for decades, very rarely deviating from it on a conceptual level. It has its heart in the right place, even if it can be a bit too traditional at times – but there’s an argument to be made that the fact that the film is able to be so predictable is actually a sign of progress, since it speaks out against the belief that every gay-themed film needs to carry a wealth of importance, almost as if it is necessary to convey a much deeper message by virtue of focusing on a marginalized community. The history of the movement is made clear, but it’s not the focus – instead, we see a group of friends (varying in personality and intellect) simply having fun and falling in love. The stakes aren’t particularly high, and the resolution can be seen from miles away, but yet still be as emotionally resonant as any other great romantic comedy, which is an immense step forward for queer cinema.

As one of the year’s most unexpectedly affecting comedies, Fire Island is a triumph, a bold and ambitious queer narrative that may seem like it is following a strict pattern, but has a genuine sense of thoughtfulness that we don’t often see from romantic comedies, which have become a genre that almost feels as if it is always going through the emotions, which is sharply contrasted by the level of nuance evoked by those involved in this particular film. almost as if they were making it clear how much having such a platform meant to them. Queer storytelling is certainly a much more widely-accepted component of modern cinema, but we still have a long way to go – the very existence of a film like Fire Island is something of a miracle, but we can also view the fact that it was viewed as an event, a rare and bespoke instance of a film about the queer community written and directed, as well as starring, people from this very community, is still further proof that we have quite a long way to go until these stories are normalized. Yet, even considering how much of a gamble it was for this film to be made in the first place, we can’t spend too much time pondering the future, when our focus should be on celebrating this film’s existence as a whole, which is certainly not a bad way to approach it. Hilarious, upbeat and heartwarming, Fire Island does its best to bridge a gap that has gradually been getting smaller as more queer filmmakers are given the chance to tell their stories – and like many recent films about the experience of being part of the LGBTQIA+ community, it never feels as if the film is trying to encapsulate the entire experience, instead choosing to tell a small but meaningful story, which is just as important as those that aim to look at broader issues. Whatever approach one takes to this film, it’s impossible to deny its appeal, and while it may not be perfect, it has a mighty soul and a wicked sense of humour, which (when coupled with the subject matter) have all the makings of a future classic, becoming the exact kind of theoretical artistic haven that this film was desperately seeking – if you cannot find inspiration, the next best option is to inspire the future generations, which is perhaps the most effective aspect of this entire film.