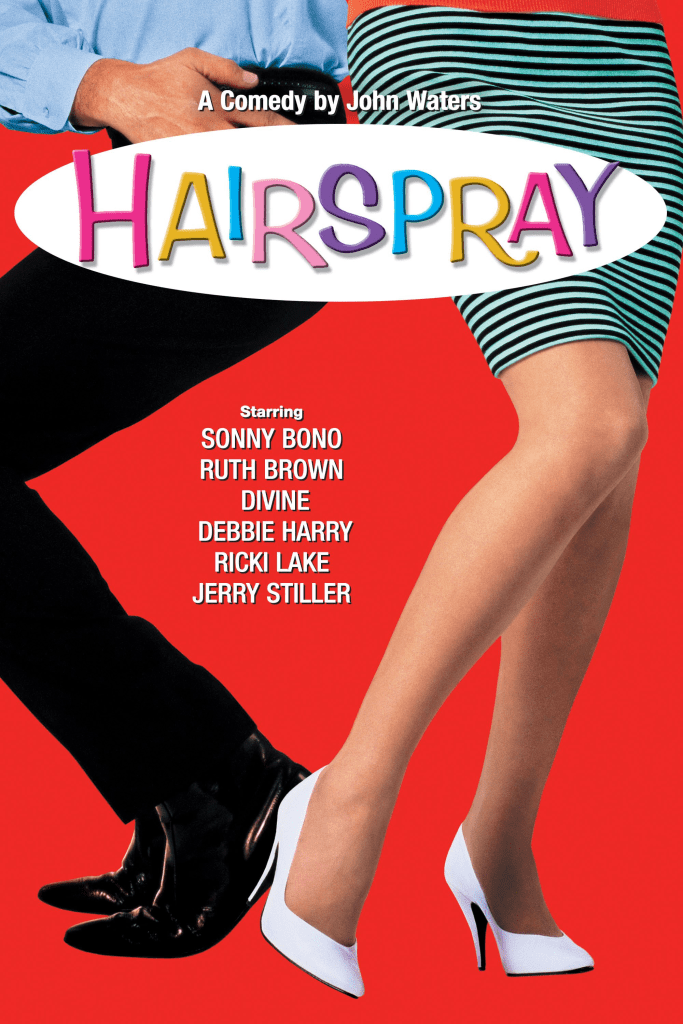

If there is a complaint that one can find when it comes to the subject of Hairspray, it would be how inconceivably enormous it has become. Whether it be the elaborate stage musical (which has been produced both professionally and by amateur theatre groups) or the film adaptation that remains one of the most profitable screen musicals in history, the story of Tracy Turnblad and her group of friends fighting for integration in 1960s Baltimore has become a notable part of our culture – and the only problem with this is that sometimes we neglect to acknowledge where it all started. The origin of the show that has become nothing short of a cultural phenomenon is in the depraved mind of the incredible John Waters, who (for the first, and possibly only, time in his career) made a family-friendly film – and while we may appreciate the joyful exuberance of the later adaptations, nothing quite comes as close to the raw vision the director had when constructing this upbeat and hilariously irreverent tale of pride and prejudice. There are many arguments to be made about this being Waters’ greatest work, and whether or not one agrees with this sentiment, its categorically impossible to deny both the raw power of the film on its own, as well as the impact it made on the filmmaking landscape, which proved that anyone can pull together a riveting film should they have the necessary skills and patience to do so. Waters has this in an abundance, and he produces a work of staggering brilliance, crafting a hilarious but deeply melancholy tribute to the past, done in that distinctive sardonic, witty style that we can not only come to expect from the filmmaker, but also deeply adore.

Regardless of whether you’re watching it for the first time or revisiting the film, Hairspray remains a fresh and invigorating work of art, a series of hilarious moments carefully curated by Waters, who momentarily puts aside his many honorary titles (which include “The Prince of Puke”, “Sultan of Sleaze” and perhaps most well-known, “The Pope of Trash”) to make something very different from everything he was known for. The differences here are notable to the point of being the aspect that most remember about the film – the lack of profanity and overt sexualization, the refusal to condone violence or prejudice of any kind, and (perhaps most shockingly of all), an ending that is not only happy, but also hopeful, which cannot be said for any of the films he made before this one. We notice these details from the very beginning, and carefully watch as Waters explores this previously untrodden territory – and while he would try and replicate a similar tone later on with films like Cry-Baby and Pecker, neither one of these come close to becoming the sensation that served to be the ultimate fate for Hairspray, a film that immediately caught viewers’ gaze, and allowed even the most ardent detractors of the director’s work to stop and pay attention, which is not something that we often see from filmmakers with as controversial reputation as Waters – but having aged into one of our great elder statesmen of contemporary art (or rather, the world itself evolved to see his perspective as just as valuable, since he has always been unabashedly himself throughout the years, even when making this film), we’re inclined to follow his work with a much greater level of interest, if only to uncover the many subversive secrets that lurk beneath the surface of this seemingly innocent film.

However, as much as we are tempted to refer to it as conventional, Hairspray doesn’t come close to following the rules, instead actively breaking them in the way only someone as demented as Waters could achieve. On the surface, the film looks innocuous, but if we peer just below, we can see how cleverly Waters creates something radical. He has often stated that he considers this to be his most revolutionary film, if only because it served to be a gateway to his other work, with his amusement at the potential of families seeing this film and, having been thoroughly charmed, going out in search of more of his work, with the likely results being funnier the more one thinks about it. It truly is a work of very intelligent satire, since the humour doesn’t dwell in the subject matter itself, but rather on what it represents, which is why we can’t limit our opinion to just the later adaptations, which are more focused on spectacle than they are substance, as wonderful as they may be. The great irony of Hairspray is that suddenly Waters was being embraced by the industry that had previously rejected him, using him as an easy target for their fury-fueled diatribes about bad taste – and not only did he embrace this label, he reconfigured it into the form of a brilliantly subversive comedy that intentionally doesn’t reach the perverted heights of his previous work, but rather retains the same revolutionary spirit that drew audiences to him in the first place, while infiltrating the very institutions that saw his art as being inferior, when in reality it was some of the most effective and transgressive experimental cinema ever to be produced.

Putting aside what the film represents, we can see that Hairspray, even when taken on its own terms, is an incredibly well-made piece of cinema. The film moves along at a steady pace, and possesses a certain rhythm that is difficult to describe in words, and can really only be felt to be understood. As is the case for most of his work, Waters’ approach here is to invite audiences on this journey with him as he leaps into the neighbourhoods that nurtured him as a young artist – during the era depicted, Waters was a young and rambunctious amateur filmmaker, producing low-budget films that were shocking in terms of both subject matter and visual prowess, and he clearly looks on the period with a sense of genuine fondness. You can feel the absolute adoration the director has for this moment in the past reflected in every frame of the film, and while some may incorrectly state that Waters was trying to make a film that appealed to a wider audience (which is perhaps only partially true), the reality is that he was more likely compelled to tell this story based on his desire to pay tribute to Baltimore as he remembers it, not the poverty-stricken, working-class neighbourhoods that are often seen as being dangerous for outsiders, but rather a vibrant, wholesome landscape built on community values. Even the most maniacal villains are charming in a way that we grow to appreciate them, and the overall message, while perhaps slightly sentimental, does show that beneath that transgressive sense of humour, Waters did find some space for hope, using it in at least one of his films, which makes a big difference. We may not necessarily want him to make more widely-accessible work, but it would certainly not be a waste of his talents if he were to produce something of this calibre – although considering how we are going on two decades since his last directorial outing, any film he chooses to make would be massively appreciated.

Like all of his films, a discussion of Hairspray would not be complete without mentioning the actors. As a director with a firm vision, it was imperative that Waters cast the right people to help realize his very strange worldview. This resulted in the creation of the group informally dubbed The Dreamlanders, the regular set of collaborators that had more criminal citations than they did acting experience, which is part of their appeal, since most of the director’s work dealt with outsiders. Hairspray is quite light on drawing from this pool of actors, with only a few of his regular collaborators finding their way into the film. Of course, the most notable presence is the wonderful Divine in what was to be his final film role, the last chance for him to work with Waters before his untimely death. For someone who mostly played transgressive women with psychopathic streaks and a tendency towards violence, Divine was remarkably warm when he needed to be, and his maternal instincts are the driving force behind his performance as Edna Turnblad. His chemistry with Dreamland newcomers Jerry Stiller and Ricki Lake was staggering, with the trio heading a cast that included many icons, likely drawn to appear in this film not as a favour to Waters, but rather as a means to pay tribute to the 1960s in their own way. You cannot look at a frame of Hairspray without seeing either a seasoned veteran having a good time, or a younger actor making a very promising debut – and Waters’ ability to draw out the brilliance from his entire cast is one of the primary reasons this film has become such a sensation.

When it comes to Hairspray, there is very little for us to say that has not been said already. It’s not Waters’ greatest work, nor is it his most influential (the former is up for debate, but Pink Flamingos comfortable takes the title of the latter), but it is the one that has been most widely seen in some way, whether in its original form, or as one of the many adaptations we’ve seen on stage and screen. There aren’t many stories that can boast having been told in film, on television and on the stage, especially not one that deals with some tricky subjects – but Hairspray is nothing if not a worthy candidate for such an achievement. From a quaint little comedy about an overweight teenager using her platform to fight for inclusion, to a global sensation, it’s difficult to deny the appeal of this story, and it all started with a well-known provocateur choosing to pursue something more gentle (although not at all less effective or intelligent in how it satirizes certain concepts), resulting in a film that has become timeless, a wonderfully exuberant and genuinely exciting work that has aged exceptionally well, with the bright colours, hilarious sense of humour and unforgettable characters working in tandem to create something so remarkably distinct, it’s simply impossible to resist the endless charms that are associated with this absolutely brilliant film that proves that even those who make their career by shocking people are capable of making something almost universally appealing – and knowing John Waters, it’s likely he considers this his most experimental, subversive work yet.