You’d be hard-pressed to find someone who has experienced Harvey and not come out of with some degree of appreciation for this joyful little comedy, or at least a certain fondness for its outright peculiarities. Henry Koster’s adaptation of the play by Mary Chase is an iconic and cherished work of the Golden Age of Hollywood, the kind of endearing, humour-filled parable that is both entertaining and insightful, often at the exact same time. There are numerous reasons to adore Harvey, but they all come down to the fact that it is the result of a lot of laborious effort, both in terms of the filmmakers who put this story together, and the audience, who soon learn that suspension of disbelief is vitally important to such a film succeeding. Not too many words need to be written to convince one of Harvey‘s status as one of the most charming films produced during this particular era, as it is comfortably adored as one of the finest comedies of the 1950s, often appearing on lists and in articles around the best works produced at the time. Yet, it still remains a source of a lot of joy, whether it be for those jumping into this abstract world for the first time, or revisiting the film to once again experience the trials and tribulations of Elwood P. Dowd and his 6-foot-tall (or rather, 6 foot, 3 inches and a half, to be precise) companion, as well as his frustrated family who are tired of dealing with a man so hopelessly lost in his own imagination, it is starting to erode their own sanity. This eventually leads to the creation of one of the most lovable adventures into the human condition ever committed to film, creating a film that is just a delight in every way, and a true joy to experience.

Writing about Harvey is more difficult than it would seem, because not only is this a film that is relatively well-regarded already, with audiences responding to it for several decades now, but it’s also a film that functions less as a coherent, straightforward story with a deeper message, but rather a bundle of joyful quirks that would not have worked without the commitment from those on both sides of the camera. Inarguably, the stage-based origins of this film are seen throughout – it is centred on a small group of characters, takes place in a few limited locations, and has an emphasis on the abstract, which is certainly something that theatre has always used when it comes to more experimental works (and referring to Harvey as such may seem peculiar, but it makes sense when you consider both the story this film is telling, and the era in which it was made). Interestingly, outside of expanding the world of the play slightly further than the stage would allow, Koster doesn’t change too much in terms of how the story is told. This is doubly impressive when we consider that this film occurred at the beginning of a decade where Hollywood was starting to make some fascinating technological progress, which means that there were ways to add supernatural overtones to this film – but while doing this may have aided in the narrative, the film would’ve lost its wonderfully surreal tone, which depends less on what we see, and more on the atmosphere evoked by the film, which is indebted entirely to the quirky nature of the story, and the fact that we never really get the answers we are seeking, an intentional but fascinating choice that contributes to the general mood of this comedic gem.

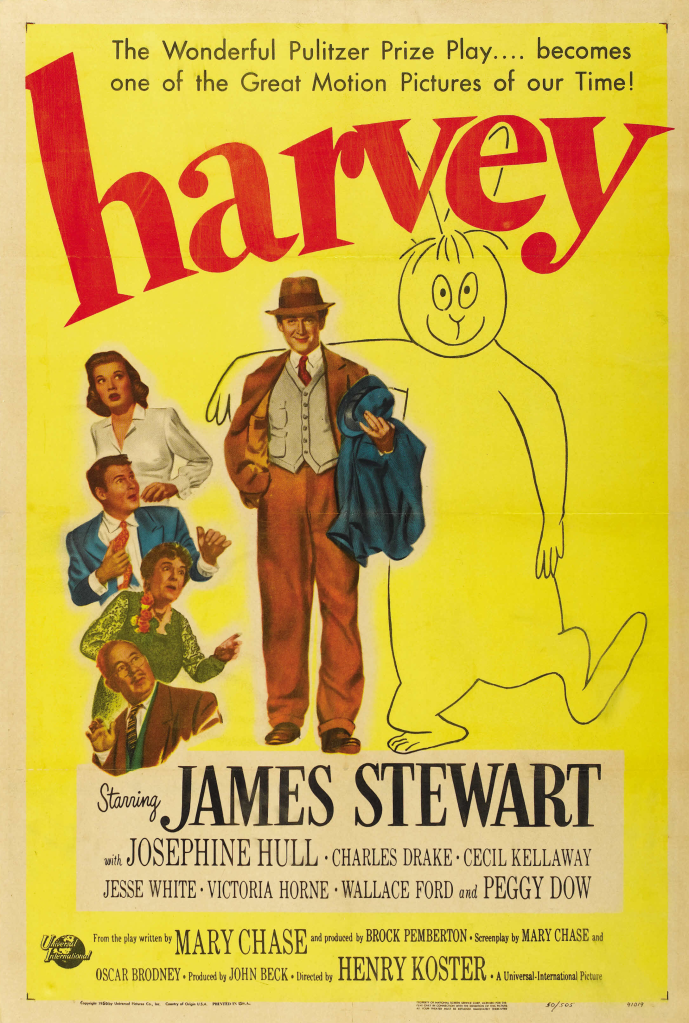

Koster certainly had the right idea in casting James Stewart as the central character of Elwood P. Dowd, whose entire personality could be summarized by his quote that “In this world, you must be oh so smart, or oh so pleasant. Well, for years I was smart. I recommend pleasant” – and no one embodies the concept of being both smart and pleasant quite like the perpetually genial and charismatic Stewart, who commands this film with the lovable energy that audiences have appreciated since his debut over eighty years ago. Having a star like Stewart in the role was essential, since the audience have to not only suspend our disbelief around the potential existence of the titular rabbit, but also genuinely believe that Elwood is a perfectly sane man who just so happens to believe that his companion is an enormous rabbit that follows him everywhere, without coming across as unhinged or mentally unstable. It’s one of the esteemed actor’s most endearing performances, where his everyman charms and magnetism work in his favour to create something extremely special, from which the rest of the film is built. Kudos must also go to the rest of the cast, who had the enviable task of interacting with Stewart, often playing the patsy to his character’s supposed delusions – veteran character actress Josephine Hull is a riot as Elwood’s selfish sister who allows her high-society aspirations to get in the way of her treating her brother with the care he requires, while Cecil Kellaway is a scene-stealer as the strict psychiatrist who realizes that his supposed expertise may be entirely wrong after being convinced that this very special psychological case may not be that far-fetched at all. As is often the case with films that originated as stageplays, Harvey depends on its cast to sell us on the story, and this is certainly the case with this memorable ensemble, all of whom are doing excellent and complex work.

It is quite tough to be thoughtfully penetrating when it comes to Harvey, since its a film that makes sure that everything is presented at face value, the most fundamental queries around the human condition being found on the surface level, rather than requiring us to scramble through the narrative, combing every word to extract the message of the film. You can’t dig for meaning when it is told to you quite explicitly – and while it sounds like this reduces Harvey to nothing more than an overly-simple work filled with unnecessary exposition, it’s the film’s most genuinely interesting component, the element that keeps us engaged and interested, since it adds a layer of nuance and earnestness to a film that is perpetually aiming to satisfy its central goal – to entertain as many members of the audience as possible. This is one of those comedies that really doesn’t have a specific demographic that is being targetted – it’s harmless enough to appeal to younger viewers, while having a lot of interesting commentary that would entice more adult members of the audience, striking the perfect balance and becoming one of the more interesting examples of family-friendly filmmaking (and considering it was made only a few years after It’s a Wonderful Life, one has to wonder whether Stewart’s presence, combined with the upbeat nature of the film, was done to intentionally capitalize on the popularity of that Christmas classic). It keeps everything it wants to say restricted to the most simple narrative territory, and allows us the chance to actively engage with the curiously charming message at the heart of the film.

Harvey is one of the sweetest, most endearing films of its era, the rare kind of film focused on exploring mental illness in a way that isn’t condescending or mocking, but rather compassionate, drawing its humour less from positioning the main character as some disturbed, crazed lunatic, but rather showing that the real madness resides in those around him, the deeply disturbed individuals who don’t quite understand that sometimes, delusions are more telling of one’s mental state than anything else, and that the most sane people do tend to have their heads screwed on the wrong way from time to time. Anchored by Stewart in one of his most charismatic performances, and told with the kind of humourous empathy that many comedies at the time employed, it’s truly difficult to not absolutely adore Harvey, a film that dares to be a heartwarming excursion into the lives of a group of lovable character, while being unexpectedly shattering, especially in the final moments when we find ourselves falling deeply in love with Elwood, investing in his relationship with Harvey, almost to the point where we start to believe Harvey is real ourselves – and there may even be a legitimate case to be made that he is indeed real, as the film continuously pushes forward with the narrative that sometimes surrendering to the fact that we don’t have all the answers, and just accepting that we don’t know everything, is perhaps the most liberating experience of them all.