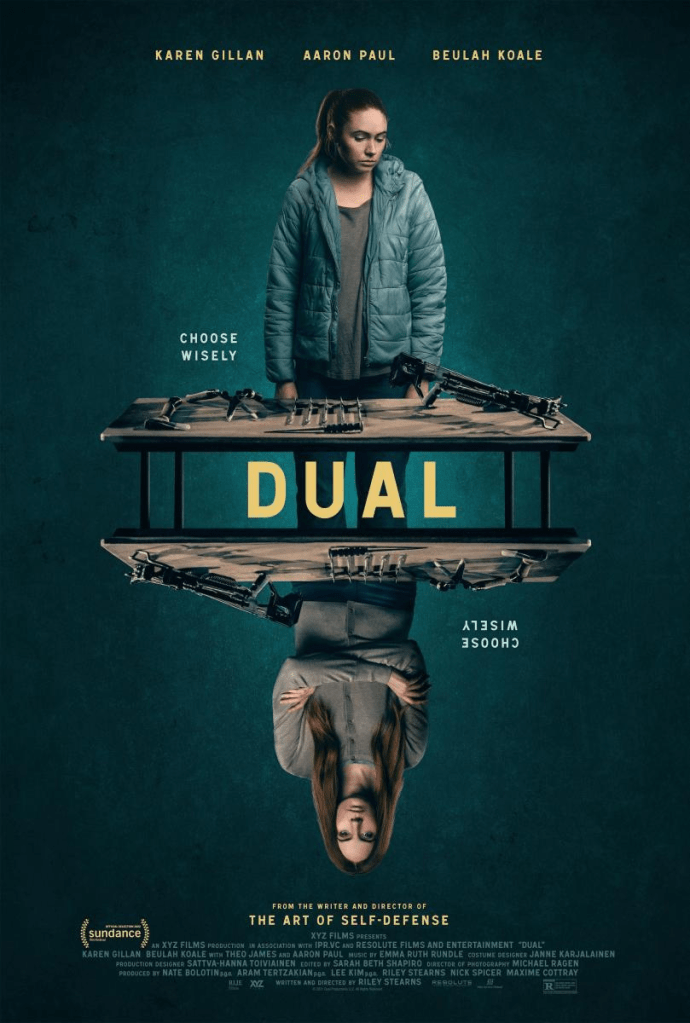

Something that never fails to surprise me as a film lover is how, despite seemingly having told every kind of story, certain filmmakers still manage to find new ideas, even if it means working with more conventional material, and in the process finding unique ways to deliver them. Riley Stearns isn’t very well-known to those outside of the world of independent cinema, but he is someone whose status is gradually growing as a result of some of his recent input. The Art of Self-Defence (his sophomore directorial effort) was a flawed film in many ways, particularly in how it captures a very specific kind of social satire, but showed considerable promise, so much that it piqued the curiosity of many viewers, who were waiting on tenterhooks to see what his next film would be. The answer came in the form of Dual, the director’s attempt at the science fiction genre, albeit with all the qualities we’d expect from a director known for his experimental perspective. Telling the story of a woman who learns that she is terminally ill, and undergoes a procedure to have herself cloned, only to discover that she has made a full recovery, leading to a situation where she and her clone need to fight to the death in order to determine which one will remain alive, as per legal conventions. A fascinating, character-based film that grapples the line between satire and psychological horror, Dual is one of the year’s more fascinating novelties, a peculiar but well-constructed thriller with a strong set of ideas and an even more precise directorial vision, which continues to establish Stearns as one of our more interesting contemporary filmmakers, and someone whose ideas may not be accessible to casual viewers (especially those expecting something slightly more traditional from this premise), but who rather actively pushes his craft in an unexpected direction, which is one of his strengths, as reflected in this film.

At a cursory glance, Dual doesn’t seem all that impressive, at least not in terms of being a particularly well-constructed science fiction film, since it doesn’t really bear many similarities to the genre on a tonal or visual level. However, this is where the brilliance resides – rather than being a work that centres around far-fetched concepts, Dual approaches the genre from a much more subtle perspective, showing that the near future is not the technologically-innovative utopia (or dystopia, considering the tone of the film) that most science fiction films tend to propose, but rather that it is certainly going to resemble the world we live in right now, with only minor alterations. It’s a much more simple look at what the future may be, which is not only economical on the part of Stearns, who uses his slightly more limited resources very well, but also from a conceptual level, since it evokes a much more subtle proposal of a future that we may very well see in our lifetimes, at least in terms of some of the ideas that propel the story. This is a detail-oriented film, one that makes better use of the more intricately-plotted aspects of the story than it does the broader moments, which are almost inconsequential to the overall product. For those expecting something that has a neat resolution, Dual may be unbearable, since this is not a film that aims to satisfy in any conceivable way. Stearns is almost too provocative as a filmmaker to have widespread appeal, but for the niche audiences that can align themselves with his deranged worldview, Dual is a fascinating effort that continues to showcase that there is certainly space for more off-kilter narratives in contemporary cinema, even if they reside slightly out of view.

In constructing the film, Stearns seems to be inspired by the more stonefaced, deadpan sensibilities of the likes of Yorgos Lanthimos and Jim Jarmusch, who regularly deliver dark comedies that are simmering with a very unique kind of humour that may be an acquired taste, but work magnificently in context for those who are aligned with this kind of bleak absurdist humour. The film is intentionally quite stilted (and it is fascinating to consider that it was filmed in Finland, since a lot of the film hearkens back to the miserablist comedy of Scandinavian filmmakers like Aki Kaurismäki and Roy Andersson). Dual is the rare kind of science fiction film that isn’t propelled by discussions around technological innovation or any kind of tangible progression, but rather centres itself around conversations on existentialism. It’s a film driven by its philosophical underpinnings, which can immediately be divisive when it comes to establishing an audience, since many will be enticed by the concept of a woman and her clone engaging in hand-to-hand combat, but may be taken aback by how subtle the film is in terms of actually showing this side of the story, with much of the narrative being around more existential issues, which may not be what everyone may have bargained for when venturing into this film. Naturally, there is much to the story than this, especially since Dual is invested in interrogating issues much deeper than just the bizarre concept of someone fighting with themselves for dominance. Questions around identity, reality and individuality are all integral to the story, and Stearns manages to often put aside the weird humour and embrace these more riveting concepts, using the jagged satirical edges as a source of support, rather than as the primary motivation for the film’s existence.

At the heart of Dual is a very committed performance by Karen Gillan, who plays the main character, as well as her clone. I’m reluctant to call this a particularly great portrayal, because its sometimes difficult to discern whether Gillan is intentionally quite stilted (which would make sense in the context of the film, based on the tone), or if she’s trying her best to make sense of the already very bizarre story. She certainly does manage to lean into the absurdity of the narrative, which inclines me to the belief that everything she is doing here is purposeful. It’s a great performance from an actress who has often been undervalued as a dramatic performer, being more well-known for mainstream fare in which she is always well-used, but rarely in a way that feels like she is operating at her full potential. Dual is focused almost entirely on her character, and she frequently finds new ways to handle the sometimes challenging material – it isn’t common to find well-crafted films in which one actor is playing both the protagonist and antagonist, and the fact that she manages to do so with such incredible poise and elegance is a great testament to Gillan’s gifts as an actress, and will hopefully allow her to do more experimental work in the future, since she clearly has the capacity to turn in really strong work with the right material. The entire film depends on our ability to genuinely believe in the tensions that exist between Sarah and her double, and Gillan manages to effortlessly switch between the two, so much that we start to see the small details that separate the characters, each one distinct and unique, which helps in contributing to the more ambigious ending, in which we are left to ponder whether the sole survivor is the original or the clone, one of the more interesting details of this already extremely layered and complex film.

Dual isnot a film that contains a story that is wildly imaginative in theory, but it has its moments of pure brilliance, and while it may not reach the bitterly caustic wit of the director’s previous film, it is still an exceptionally strong effort that warrants a lot of attention. This is an incredibly intelligent film, one that has a keen sense of irony, and an even more playful tone. It’s not always the most straightforward, and the viewer has to actively pay attention, since a lot of the plot resides in the small details, which would be otherwise difficult to notice if there is not a concerted effort to engage with the film and its more unconventional approach to the story. There’s an atmosphere of absurdity that guides the film, which is primarily the result of Stearns’ more sardonic sense of humour, which adds a level of nuance to a film that may have been unbearable without this caustic wit that implies that it knows exactly how bizarre the story may come across. It seems almost a shame that Dual is inevitably going to be seen as more of a cult film than one that is widely appreciated, since its originality in contributing to the science fiction genre, coupled with its dark sense of humour and rigorous philosophical details, make for a film that knows exactly how to engage with the viewer on a much deeper level, which only serves to make for a more compelling viewing experience, all of which amounts to a film that is guided less by narrative, and more by its atmosphere, which is a lot more interesting than a more mainstream approach to this concept may have been, once again proving that while he is constantly orbiting around the mainstream, Stearns is someone whose vision is much more integral to the niche world of independent cinema, where his brand of madness is not only accepted, but encouraged.