While his name may not be exceptionally well-known outside of devotees to the world of independent cinema, but Alexandre Rockwell is an important figure in a movement that dedicated itself, as its name would suggest, to breaking free from the shackles of mainstream Hollywood, and taking on a new form of filmmaking as a means to tell stories in their own unique way, rather than following conventions. Rockwell’s best-known work is In the Soup, a film that may or may not be autobiographical (which actually makes something of a difference once we reach the film’s final narrative destination), and offers his own perspective on the state of the industry at this formative moment in time. The film focuses on a young, burgeoning filmmaker who may have talent and ambition, but lacks one small, vital detail – he has yet to make a single film, proving that his title is slightly presumptuous. This is until he encounters a mysterious older man who may not know much about filmmaking, but certainly has enough money to give off the impression that he does, with any promising young director yearning to come across someone as liberal with their money as this man of an indeterminate profession (or even origins, although very likely drawn from the world of the explicitly illegal and immoral), who seems all too willing to part with his wealth in order to make the dreams of some foolish young soul come true. In the Soup is a wonderful film – a sweet and hilarious independent comedy that takes a wonderfully bizarre tone as it immerses us in the world of amateur filmmaking, taking us on a journey into the life of one particular filmmaker who struggles to make ends meet already, so endeavouring to make any kind of film (let alone a 500-page existential philosophy epic) is going to be a challenge, regardless of the avenues he takes to make it happen.

If one has never heard of In the Soup, the most likely explanation would be that it isn’t particularly well-known, a result of the fact that this is independent filmmaking in its purest form. Despite having a few recognizable faces in the cast, the film as a whole is the work of a director who gathered a few of his friends and decided to make a film – produced with a shoestring budget, and made in only a few limited locations, it is the kind of independent film that truly honours this epithet, ensuring that every moment is drawn from the most authentic narrative spaces. Rockwell was not a major name in the industry – other than a few small-scale productions that are now mostly forgotten by everyone except those involved in their creation, and existing mainly as a footnote from which we can start the discussion on In the Soup, this was his first major foray into filmmaking, an ambitious choice, considering how much this film seems to be drawn from reality. Rockwell is a major talent – his screenplay is sharp and scathing, brutally eviscerating the industry in which we was working (or at least trying to work – he never truly did make it to the mainstream after all) in between striking comments on the nature of art, and how it intersects with romance. His directing isn’t any less impressive, with the very bare style of the film not precluding the director from taking a few visual risks to go alongside the multilayered narrative. They work in tandem with each other, consistently drawing inspiration from what the director experienced as a young, budding filmmaker in the 1980s, much of which is carried over and embedded into the fabric of this film, which benefits massively from his unique perspective.

In the Soup is a very funny film, but its philosophical intentions are not restricted to the fictional “film within a film” that serves as the foundation for the story. There is a deep sense of existential ponderings occurring throughout this film, with Rockwell seemingly using this platform as a way to work through his own experiences as a young filmmaker trying to get a project funded and brought to fruition. As a result, In the Soup is as much a satire of the cutthroat world of independent filmmaking as it is a poignant meditation on the artistic process. The character of Aldolfo Rollo (who we have to assume is based on the director) is consistently questioning his chosen career – he knows that he is an artist, but one that is stuck in that supposed “rough period” that he claims all great creative minds have to endure before finally being noticed, which in his case comes on behalf of the character of Joe, who makes him an offer he’d be foolish to refuse. However, the film doesn’t descend into the same kind of Faustian satire that we’d expect from this premise – there aren’t any real twists or turns, nor are there moments of deception, with the genuine fondness between the two main characters being felt constantly throughout. Rockwell is clearly not focused on abiding by conventions, instead using every opportunity to assert his experiences through the adventures of his protagonist. It leads to an abundance of hilarious situations that make In the Soup a really charming comedy, but also lends it a dramatic gravitas that allows him to ponder a few major issues that would otherwise not be found in a more straightforward satire. It’s easy to tell when a film like this was made for the sake of poking fun at a popular form of the media, or if it was the product of laborious effort on the part of someone dedicated to their craft, and both narrative and structurally, In the Soup epitomizes the latter.

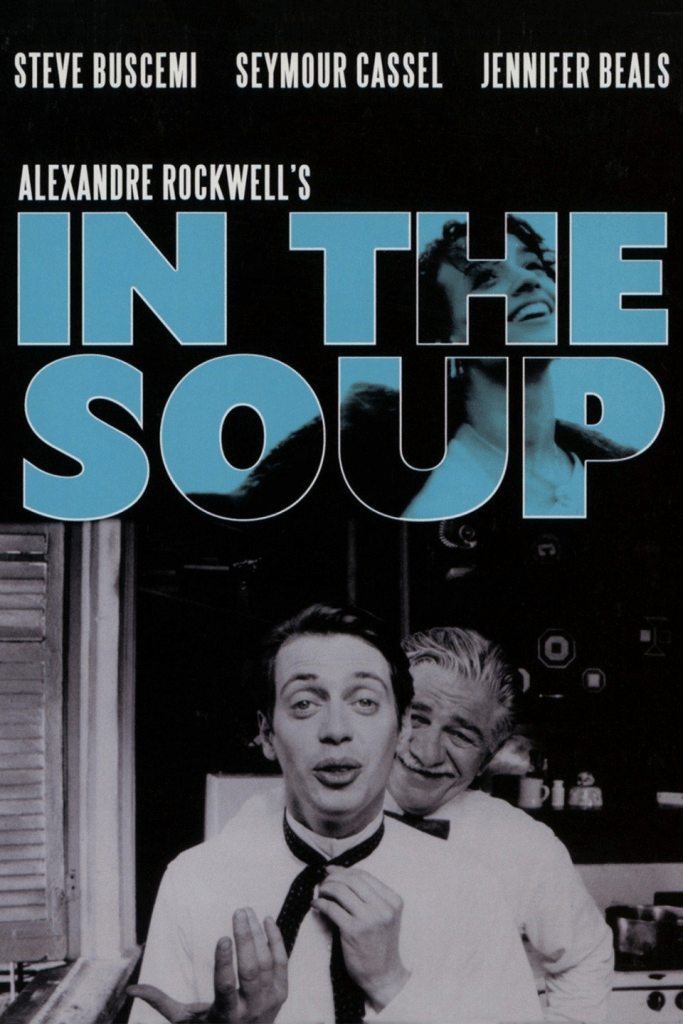

As we’d expect from such a story, In the Soup is a very loosely-structured film. Independent comedies in the 1990s weren’t driven so much by narrative as they were atmosphere – and while there were clear intentions lurking beneath this film, as mentioned above, the story itself is really just a series of interconnected vignettes that give us glimpses into a few weeks in the life of the main character, and a few of the other individuals with whom he interacts during this time. It’s an actor-based film, and naturally required strong performers to play the roles, which come mainly in the form of the two leads, Steve Buscemi and Seymour Cassel, both of them the definition of journeymen actors that were willing to take on any material, granted it provided them with some interesting work. Buscemi is the perfect person to play the semi-fictionalized version of the director – he’s an eccentric actor with a very clear set of skills, amongst them being able to play likeable characters without having any particularly strong qualities other than their strong resolve. He had done quite a bit of strong work prior to In the Soup, so it wouldn’t be right to call this his breakthrough as an actor – however, as someone who has led a fruitful career as one of the most important figures in independent cinema, this film felt like a watershed moment. We don’t even need to dig too deep into Cassel’s career to note his standing in the industry, since he remains the gold standard when it comes to character actors, someone always willing to show up, regardless of the size of the role. It helps that he was a formative figure in the creation of independent cinema when it was still in its relative infancy, working with directors like John Cassavetes and (later in his career) Wes Anderson in some of their earliest projects, lending his talents to their films, while receiving the chance to do earth-shattering work in the process. Rockwell utilizes his two stars extremely well, and consistently draws our attention to their well-known strengths, while still challenging them to push themselves further than we’d expect, which likely gives the film its distinctly acerbic tone.

In the Soup is such a captivating film that would be enticing to anyone with even the vaguest interest in the world of independent cinema, which has now evolved into a more polished and accessible corner of the industry, but only as a result of the growing popularity that took years to achieve, and remains an ongoing battle, especially in an era where a film’s modesty and simplicity is seemingly being weaponized (some may even say fetishized) by the industry, who now equates the term “independent” with concepts such as subversive narratives, provocative stories and against-type performance from major actors. This could not be further from the truth when it comes to this film and those produced under the same general artistic umbrella – what inspired Rockwell to make this film in particular remains to be seen exactly, but it certainly is clear from the first moment that it was designed to be something that allowed him to represent his craft along his own terms, telling a story that may not be entirely resonant to the wider audience, but would appeal to any artistically-minded young person who is struggling to have their voice heard and works noticed. It’s an oddly compassionate film, which we may not have expected considering the very nihilistic, caustic nature of the narrative, and the dialogue from which many of the film’s primary ideas are formed. Ultimately, In the Soup is a delightfully irreverent and surprisingly heartfelt tribute to independent filmmaking, telling a simple but effective story of a young man trying to make a film – and as it goes along, the meta-fictional elements start to appear, which adds layers of interesting discussion onto a film that has already stirred enough thoughts without having to make us question whether Rockwell was merely telling a story to which he could relate, or actually narrating his own journey as an independent filmmaker. Regardless of the approach we take in trying to understand this film, there’s a sense of blissful authenticity that informs it and turns it into such a wonderfully insightful, and frequently absurd, glimpse into the inner machinations of the artistic process, and the various challenges those who yearn for fame, but still ferociously grasp their independent spirit, tend to encounter, which should be quite relatable for any artist, who will likely see themselves reflected in some way through this peculiar film.