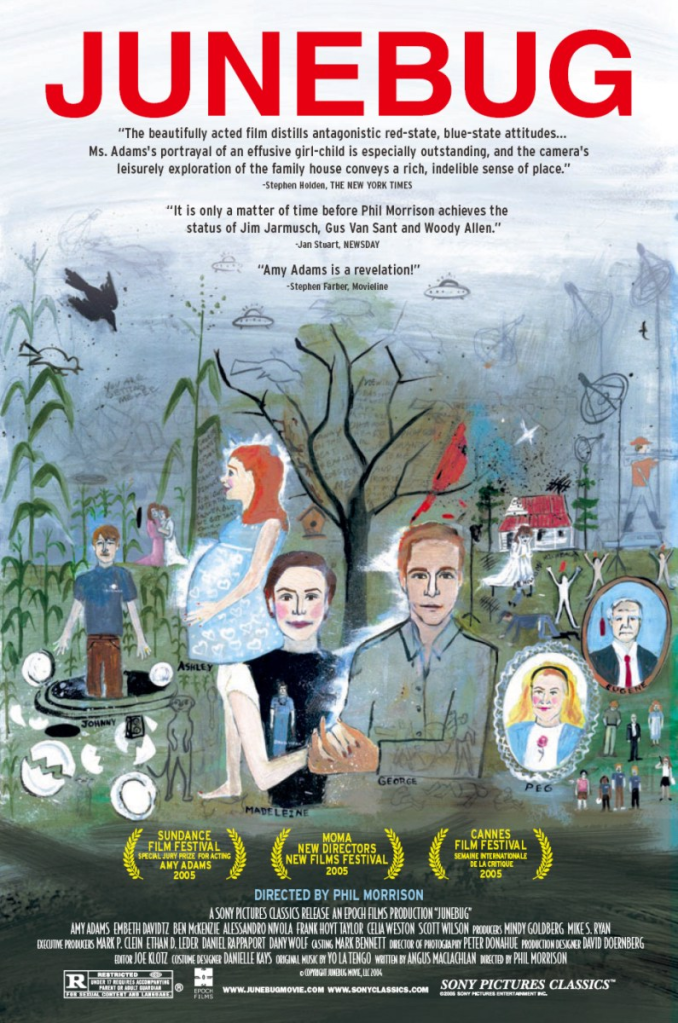

As we’ve discussed numerous times, independent cinema has had quite a storied history, with the roots going back just about as far as film has been considered a legitimate medium – for every major production, there were a dozen smaller works that were obscured by the unimpeachable might of the mainstream industry, but which have been discovered and appreciated by a smaller but far more passionate faction of the global audience. The independent movement can be divided into countless different sub-sections, depending on any parameter, ranging from era in which they were made to the specific socio-cultural milieux in which they took place. The early 2000s were a watershed moment for American independent films, with the rise of auteur theory amongst the new generation of filmmakers, as well as the gradual recognition of smaller works as worthwhile art leading to a rise in popularity that has not only failed to abate, but has only increased in popularity. Junebug is a fascinating case of a film – written by Angus MacLachlan and directed by Phil Morrison in his directorial debut, the film is a charming comedy about cultural differences that draw out some terrific performances from its strong cast, and which may not be the most perfectly-constructed work, but has a sincerity that makes it a lot better than it would often seem to be based on the central themes that it is actively trying to explore. This is the quintessential upbeat family comedy that has overtures of melodrama, and while it may not always be entirely successful in looking at some of its main ideas, it is enough to keep us engaged and interested, which is valuable in its own unique way.

If there is a central flaw to Junebug, it would likely be that it runs a few beats too long. However, this doesn’t have anything to do with the tangible length, but rather what Morrison does with it. Running at a neat 100 minutes, the film is relatively conventional in terms of duration – the problem is that it feels somewhat imbalanced. The first hour is measured in pace, taking its time to establish these characters and the setting in a way that is bordering on meandering. This is perfectly fine, since there is an argument to be made in favour of more intentionally slow cinema as a legitimate means to tell a story. However, there is still a lot of plot in this film, and it is unfortunately compressed into the final act, where we are witness to far too much activity, which once again would have been reasonable had the previous two acts been done with more precision. Junebug is a film composed of two very different halves – they tell the same story, but they don’t quite meet in the middle in the way that should perhaps ought to have, which leads to the film feeling quite jagged and unnecessarily convoluted in moments that should have felt more natural. The disconnect between the two parts of the film feel glaring – we can tell that it was written by someone who primarily worked in theatre, since the emphasis on a single location, as well as the abundance of monologues and extended conversations, makes Junebug feel like it was transposed from stage to screen, and Morrison doesn’t do too much in terms of directorial flourishes to change our perception. It doesn’t invalidate the film as a whole, but rather softens the impact that would’ve been far more impressive had there been slightly more effort put into ensuring that it flowed as a single coherent piece, rather than a series of conversations orbiting around the same unspoken subjects that the audience is somehow meant to automatically recognize based on nothing more than a few contextual clues.

However, as critical as we can be about the film and its approach to the story, we should not allow execution to distract from intention, with Junebug having several merits in terms of the aims it had with telling a particular story. One of the most reliable ways to make a good film is to draw on the theory of culture shock and how this is fertile ground for some fascinating discussions, especially when it comes to the subject of family, which is often an appropriate starting point for these kinds of films. Regardless of the specific setting and the kinds of people represented, we all tend to respond to stories of outsiders finding themselves in unfamiliar terrain. In the case of this film, we have someone who is not only a foreigner within the country, but who is forced to go from the cosmopolitan metropolis of Chicago, to the backwoods simplicity of semi-rural North Carolina, where she is placed under the careful watch of the humble but discerning southern folk from which her husband emerged years before. There are some really charming and insightful demonstrations of cultural differences, and if there is something that Junebug does really well, it is making sure that there is an air of palpable tension – not necessarily the kind that feels hostile, but is rather just uncomfortable enough to keep us on edge, which is a valuable quality for a film that is seemingly focused on exploring the lengths to which a family will go to defend their honour, without actually becoming confrontational. There is an active attempt to add warmth to the film, and Morrison often seems to be adding details to what is clearly a more unforgiving screenplay that is more focused on stressing the cultural differences, rather than finding resolution to what is clearly a more complex conversation. The balance between the two is what gives Junebug its very unique spark, and helps it become more than just the sum of its parts.

There are several formidable actors that appear in the film, with Morrison casting quite a few recognizable performers. They may not be the epitome of the calibre of star that would bring in droves of viewers, but rather the solid ensemble composed of great actors that can handle challenging material, regardless of the specific details that surround them. Embeth Davidtz commands the film as the outsider forced to spend a few days with her in-laws, who she discovers stand in firm opposition to her own well-formed sensibilities, while never being even vaguely antagonistic. Instead, they’re just cut from radically different cloths, which is how the film finds both the humour and gravitas in a very simple situation. Davidtz has a very intriguing ability to find the small details in an otherwise vague character, serving as the audience surrogate (and thus not being much of an eccentric herself), but rather acting as a reactionary figure to the more offbeat characters that we meet along the way. The family includes veteran characters actors Celia Weston and Scott Wilson (both of whom are terrific, capturing the spirit of these happily ordinary southern folk that don’t aspire to much more than just the simple lives they have grown used to), as well as younger and more promising actors like Alessandro Nivola, Ben McKenzie and, in her undeniable breakout role, the wonderful Amy Adams, who is perhaps the only person genuinely aided by this film, since it brought her to the attention of a much wider audience, and allowed her to take a considerable leap within the industry that would soon value her as one of their very best performers. Adams is terrific, but she does receive most of the praise, which should be equally distributed amongst the entire cast – had one of the actors not been fully committed to the roles, it’s highly unlikely that the film would have been all that successful in the first place.

Junebug certainlyis a very gentle film, and obviously it never aims to push the audience away from any of its characters – but its intimacy can sometimes feel a bit forced, especially when there are moments where we can feel the simmering desire to be more than just this southern-based familial drama, with clear ambitions to achieve much more, which are unfortunately squandered by the film emphasizing certain ideas over others, which don’t make much sense when we consider how much could’ve been done with the material. The overt reliance in extended conversations that may give us insights into the characters themselves, but at the expense of actually doing something constructive with these themes, leads to a film that was clearly trying to achieve something much more, but struggled to find a way to encapsulate everything into a relatively brief running time. It’s difficult to fault the film – it was written and directed by a pair of artists that did not have any tangible experience working in the industry prior to this, so it seemed likely that the film would have a few challenges that it needed to overcome. However, as is often the case with debut films, the ambition outweighs the shortcomings, which are relatively minor, enough for us to not necessarily ignore them, but rather look at them not as flaws, but rather moments in which the film was showing that it was aware of the fact that it was interested in expanding on the world much more than it was given the opportunity to, which piques our interest and provokes thought and discussion that is as fascinating as any of the actual themes we see being investigated. Junebug is a fine film, an entertaining and very endearing comedy that wears its heart on its sleeve and makes its intentions known throughout, which is much more than it possibly warranted, but which makes it a charming and lovable story of embracing family, regardless of the differences that may seem like points of contention from a distance, but just add character to an already unique clan of individuals navigating some hilarious but unconventional terrain.