It may be a bold statement, but The Man with Two Brains could legitimately be the funniest film ever made. Rarely has there been a comedy that contains so much original humour that is presented at such a rapid pace, it almost becomes impossible to capture it all in a single viewing. Yet, Carl Reiner (who is definitely not someone whose comedic insights should ever be dismissed, being arguably one of the most influential humourists of any generation) proved to be just as much of a genius as always with this film, reuniting with Steve Martin, who had his own mainstream breakthrough a few years earlier under Reiner’s direction in The Jerk, which catapulted him to worldwide fame, to make this deliriously strange and incredibly funny comedy that doesn’t hesitate for a single moment to showcase the brilliance of the people involved. Such effusive praise doesn’t come easily, especially when there have been so many hilarious comedies made over the years (lists of which rarely make mention of this film), but there are far too many moments of absolute hilarity that justify such a statement, even if most of it comes from a place of profound awe at how Reiner and Martin managed to make something so profoundly stupid come across as smart, interesting and engaging – but if there was ever a duo that would be better suited to such conventions, it would be these two, who spent their entire careers pushing boundaries, and making sure audiences received something of value when venturing into one of their films, which may not have always been as effective as others, but certainly rarely failed to incite genuine laughter.

There’s something very captivating about a good science fiction comedy, especially those centred on mad scientists. One of the director’s closest friends is Mel Brooks, who laid the foundation for these kinds of films with Young Frankenstein, a highly influential comedy that blended genres and managed to find humour in every frame. Considering both Brooks and Reiner developed in the industry alongside each other, it’s logical to assume that there were shared qualities in their artistic process, similar components that carried over between films and helped them be intrinsically linked as filmmakers. One of their most common traits was the attention paid to detail – The Man with Two Brains is essentially 90-minutes of non-stop jokes, arriving in either hilarious visual gags, or spoken lines of dialogue. The comedy never truly stops throughout this film, and Reiner (as a professional of the industry) knew how dangerous it is to consistently pitch the film at the highest level of humour. Far too many works have been ruined by directors that take an almost stream-of-consciousness approach to maintaining the same level of comedy throughout, rather than undergoing a process of developing peaks and valleys from the material, which is really what a strong work of comedic fiction should strive to do. However, while the comedy is consistent and never falls away, it is worth the risk, solely because Reiner manages to infuse every frame with a different kind of humour, The Man with Two Brains running the gamut from absurdist dark comedy to broad farce, and succeeding wholeheartedly in all instances, continuously drawing out the humour in the most unexpected situations, leading to many surprises that not even the most eagle-eyed, attentive viewers could possibly see coming, which is all part of this film’s charm.

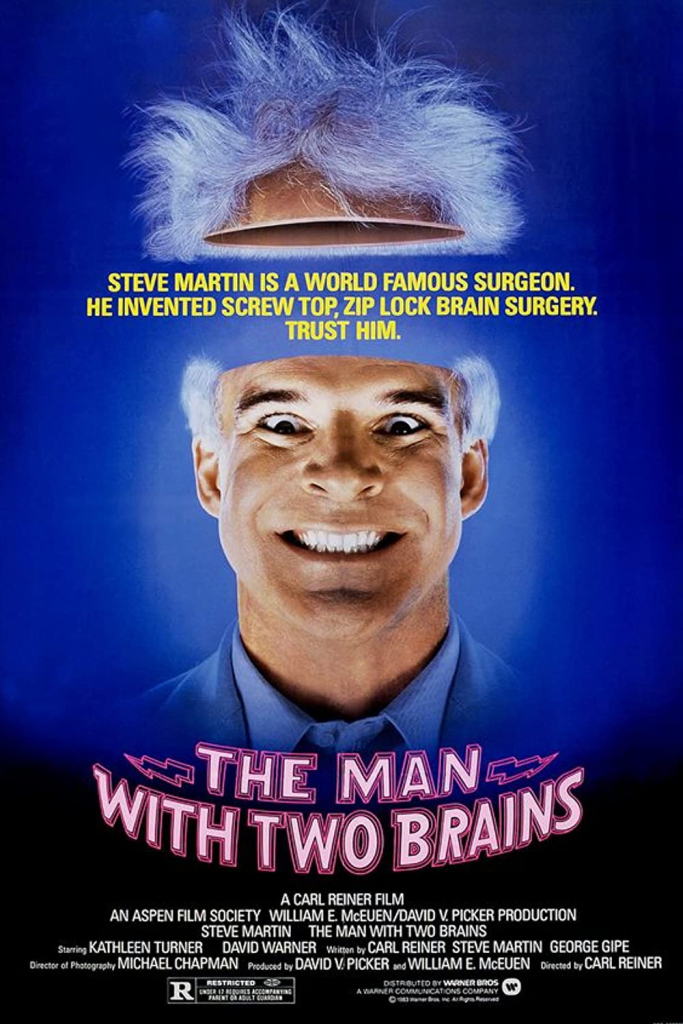

Martin has been such a strong presence in comedy over the past half a century, it is difficult to imagine the industry without him – his distinctive mop of white hair and elastic expressions making him one of the most versatile comedians working in the profession, often quite literally. The Man with Two Brains was made during the actor’s most prolific period – nearly everything he made in the 1980s carried some merit in terms of either being critically and commercially successful, or playing well with those with a penchant for alternative comedy, making him someone capable of effectively pandering to any portion of the population, granted they were willing to take some leaps of faith with his characters. This film has a tone that may be bewildering to some, but which still has a genuine fondness for Martin, who works in close collaboration with Reiner and co-writer George Gipe (who worked with the pair on their previous collaboration, the postmodern masterpiece Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid) in constructing a film that gives him a great role, allowing him to make use of his distinctive madcap energy, while also giving the spotlight to his co-stars, the most notable of which is Kathleen Turner. Still relatively new to the industry in terms of number of films, Turner was already well on her way to being one of Hollywood’s most beguiling and gifted creative minds. Her performance in The Man with Two Brains is wonderful – she’s playing the villain of the film, weaponizing both her sex appeal and ability to play very interesting characters, to craft this maniacal antagonist, drawing us in, literally seducing us in a number of ways, and being the perfect partner to Martin’s eccentric but principled protagonist. Even Sissy Spacek, who lends her voice to one of the titular brains (and remains uncredited), is given strong work, proving that there is nothing quite as powerful as a story well told, especially when it comes to great actors taking on these parts.

The Man with Two Brains draws most of its humour from the fact that Martin and Reiner never let the audience rest for even a moment, keeping us on the edge of our seats while it takes us on this peculiar voyage, frequently showing us sides of this story that would be considered far too far-fetched by anyone who doesn’t have much familiarity with how they approach humour, which has always been about finding the biggest laughs in the most unexpected locations, whether literally or metaphorically. Absurdism is an artistic movement that has given rise to many fantastic works, and while it may be relatively conventional in practice, there’s a very distinct peculiarity to the conception of this film, which is much more layered than we initially tend to see at a cursory glance. There are many more layers to this film than we originally think – what starts as a deranged comedy about a mad scientist with a love for the slimier side of science, mainly the human brain, actually becomes a very pointed satire. The question shifts from trying to understand the intention of the film, to attempting to work out precisely what is being satirized. In all honesty, this question is never really answered in its entirety – it mainly serves as a rekindling of certain themes relating to the science fiction genre, which is carefully deconstructed by this film. There are matters relating to international relations, with the oscillation between the United States and Europe (and the eccentrics contained within) making for enthralling viewing, the cultural differences leading to a range of hilarious situations that Martin and Reiner manage to exploit to their full potential, constantly provoking at certain ideas that lead to a hilariously irreverent comedy with perhaps too much ambition in terms of the scope of the humour.

By the end of The Man with Two Brains, we’re understandably at something of a loss, since this is not a film that is particularly endearing in a way that would be appealing to most viewers, with the pitch-black sense of humour, and frequently caustic approach to some very common themes making it a film that would more likely succeed amongst those who have a fondness for more absurd stories, audiences that may have a penchant for works that replace logical reasoning with a kind of bitter satire that is far more challenging than more conventional stories. Yet, it is as accessible as anything else made by Reiner and Martin, who refuse to waste a single moment on anything other than this very earnest, but darkly comical, story, which is much more complex than we’d imagine when first looking into this world. There is never a bad time to revisit The Man with Two Brains – it may not be the most famous of Martin’s notably busy decade, but it is definitely one of his best, since he is not only turning in a hilarious performance (some of his line readings leave the viewer cackling hours after the film has ended), but also a strong story that hints at a range of deeper meanings, all of which are beautifully embedded deep within this film, ripe for the picking by anyone with even the vaguest interest in looking for humour in some obscure recesses of the human condition, which is much more interesting when filtered through the perspective of a couple of artists who have very little interest in logic or decorum, and instead engage with these issues on a more abstract level, leading to a film that is hilarious, darkly comical and absolutely brilliant in every conceivable way.