If there was ever a filmmaker who knew the merit of a story well told, it would be Nicholas Ray, whose career was as diverse as it was prolific. During his peak, he directed some of the greatest films ever to be produced by Hollywood’s major studios, working in a range of genres that consolidated him as amongst the most versatile filmmakers of his generation. For many, his masterpiece is In a Lonely Place, an adaptation of the novel by Dorothy B. Hughes, which Ray carefully adapts alongside screenwriter Andrew P. Solt, to create an absolutely spellbinding and atmospheric drama that carries an enormous amount of significance, especially in looking at the heyday of the film noir, which many consider to have peaked around this time, with In a Lonely Place in particular being considered a standout entry into a genre as popular as it is ambigious, which only makes it more enthralling. Having made his directorial debut only one year before (interestingly with another film noir, They Live By Night), Ray was still a relatively inexperienced filmmaker in terms of output, but as this film proves from the first striking frame, he certainly didn’t need to possess the weathered knowledge of a seasoned veteran to pull together a range of narrative threads and forming it into this deeply unsettling but profoundly beautiful film that combines genre tropes with a deep sense of existential curiosity, which has continued to situate In a Lonely Place at the very peak of what film noir had to offer, all of which is encapsulated perfectly in this simple but evocative drama that proves not every story needs to be particularly complex in order to captivate our minds and keep us engaged.

Looking at early films noir, we’re often drawn to the fact that many of them are adaptations of novels that were not particularly well-regarded. While they may evoke a certain kind of prestige by contemporary standards, names like Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler were previously associated with cheap, disposable “dime-store” novels that weren’t often considered the pinnacle of elite literature. One of the primary reasons these stories became so popular, and developed almost folkloric reputations (outside of the nostalgia for the “good old days” of hardboiled crime fiction) is due to the efforts of directors like Ray and many of his peers, who put in a substantial amount of effort to adapt these novels in a way that was artistically resonant, even if they were sometimes just as cheaply made. In a Lonely Place is one of the more notable entries, since it features one of the biggest stars at the time in the central role, and was made with the intention of being a major success. As a writer, Hughes was not as widely known as her contemporaries, but she did possess a more artistically-motivated set of talents, which manifest in her work, and which is brought to the screen with incredible skill by Ray and his colleagues, who take her novel and create an unforgettable series of moments that draw attention to the deeply melancholy nature of her story. In a Lonely Place is wonderfully captivating, but in a way that is quite actively interesting, consistently shifting between different ideas and themes in the pursuit of some deeper meaning, not being content to simply marinade as a straightforward drama, but instead working towards a very interesting set of conversations that are exceptionally facilitated by Ray, who is doing much more than simply adapting the novel directly to the screen.

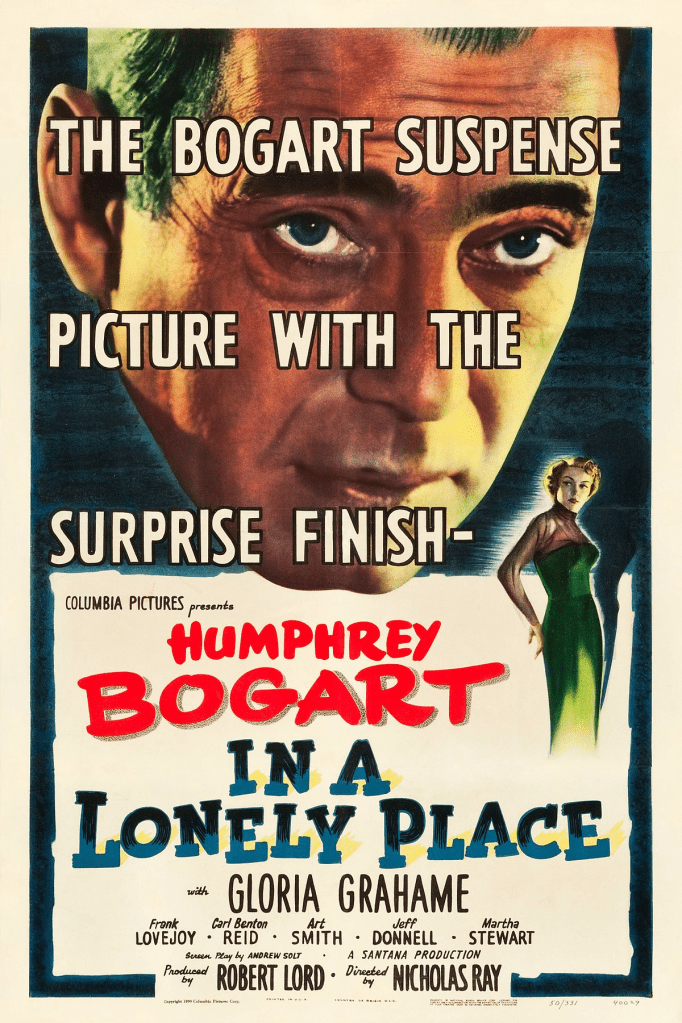

Outside of its very unique tone and atmosphere, In a Lonely Place is mainly known for the performances given by the two leads. In particular, the film was designed as a starring vehicle for Humphrey Bogart, one of Hollywood’s most successful and cherished actors, who was at the peak of his popularity at this point. Over a decade of solid work that made him quite a formidable actor in a range of genres resulted in Bogart having access to a number of fascinating roles in films that spanned multiple genres. Yet, as time has gone on, we mostly remember his work in film noir, which is where he turned in most of his interesting work. After playing arguably the most iconic characters in detective fiction (Phillip Marlowe in The Big Sleep and Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon), he clearly had developed a tendency towards these mysterious, brooding anti-heroes that were often the central figures in these stories. This time, he’s on the other side of the moral dilemma, playing Dixon Steele, the alcoholic screenwriter with anger issues who is suspected of murder – and just as he did when playing complex but virtuous heroes, Bogart brings an abundance of spirited candour and nuance to his portrayal, turning in what is quite possibly his finest performance. He is considerably aided by the wonderful Gloria Grahame, who is an absolute revelation as Laurel Gray, who is far more than just a mere love-interest for the main character, but a fully-formed, interesting individual all on her own terms that is essentially the heart of the film, functioning as both the voice of reason and the audience surrogate, the person through whose eyes we see this story unfolding. Bogart and Grahame create a dynamic duo of performances that consistently push the boundaries of the film, proving to make In a Lonely Place one of the more complex entries into a genre that sometimes neglects the practice of developing their characters beyond mere archetypes.

Simplicity is what makes In a Lonely Place so interesting, because despite having quite a complex story in terms of being a murder mystery set in the sordid backwoods of the film industry, it is remarkably straightforward. Credit must be given to Ray, who had many gifts, but primarily managed to consistently get to the point of whatever film he was making, never having too much time for floundering exposition or unnecessary sub-plots that do nothing other than complicating the main story and lengthen the film. At a quick-fire 93 minutes, In a Lonely Place doesn’t have time for unneeded components, and the director consistently draws our attention to the heart of the story, using the wonderful performances by Bogart and Grahame as the launching point for some sobering and fascinating discussions, which occur concurrently to the central plot, which is only enriched by this very direct method of developing its characters through constructing the film around them through their dialogue, rather than the other way around. There’s an authenticity to the film that I found quite striking – Ray outright refuses to allow this film to descend into sensationalism, preferring to keep it direct and simple, using the story as the start of a deep voyage into the psychological state of the main character and the other individuals woven into his journey – and the director makes sure to keep everything quite fundamental, using conventions sparingly, and preferring to allow these events to unfold organically, which lends In a Lonely Place a kind of earnest, elementary nature that works in conjunction with the evocative atmosphere to create this vivid, unpretentious journey into the mind of its protagonist.

In a Lonely Place is a terrific film, the kind of old-fashioned film noir that has a strong story that doesn’t seem too convoluted, and a lot of heartful dedication to the underlying themes, which are primarily the focus of much of the film, interwoven with the central plot, which is labyrinthine but never excessive. Ray was such a gifted filmmaker, and even when working with something slightly more challenging (especially so early in his career as a director), he managed to pull together many interesting ideas, delivering a daring and complex psychological drama that has helped define the genre, taking film noir out of the pages of cheap pulp fiction novels, and presenting them as the basis for the same kind of strong stories of stoic, complex protagonists and the various other people they encounter on their journeys, whether physical or psychological. Anchored by Bogart’s best performance, told with precision and earnest dedication to the material (which entails both respecting the source text, but also elevating it, since a direct adaptation would’ve been far too verbose), and directed with a keen authorial vision by someone whose voice as an artist was already starting to filter through, In a Lonely Place is an excellent film – complex, nuanced and interesting from beginning to end, it’s difficult to find too many films noir that executes both style and substance as effortlessly as this, which only makes it all the more riveting that we have such a raw and unfiltered glimpse into the genre, produced while it was at its peak, which leads to even more insightful and interesting discussions surrounding the style of filmmaking, and the broadly applicable messaged embedded deep within this affecting, haunting story of the human condition and the efforts to which many will go to preserve their dignity, and perhaps even sanity.