When an artist has achieved perfection (or something very close to it), it’s difficult to justify their decision to try to replicate that same success. This is the case for Joanna Hogg, whose efforts in bringing The Souvenir Part II to the screen were admirable, if not slightly bewildering, not because the film was bad in any conceivable way, but rather that the first entry into this duo of films was one of the most exquisite films of its year, and one that stands alone as a perfectly insular work of art, one that simply could not be matched, regardless of how much work Hogg put into the follow-up. However, it’s certainly not our place to question her decision to construct a second entry into her cinematic autobiography, and rather our attention should be spent looking at the unique and curious ways in which the director took the original material and built on some of the more interesting themes, while introducing an entirely new array of ideas at the same time. It may not be necessary in the traditional sense, since The Souvenir is not a film that seemed like it needed a sequel (if we can even use such a reductive term – this was clearly designed as two components in the same story, which we did not know at the time of the first film’s release), but anyone who wasn’t absolutely riveted by the idea of Hogg, who has steadily re-established herself as one of the most interesting filmmakers working in Europe today, revisiting her own past through the lens of a young woman who represents her as a young artist, someone desperately trying to stake her claim in a world that has grown increasingly hostile the more she starts to become independent, learning that adult life is not nearly as easy as many make it out to be, especially when one is following an unorthodox path, both in terms of life and their career.

In many ways, The Souvenir Part II actually manages to be quite different from the previous film, which is an interesting development in a landscape in which sequels are made as a means to parrot the formulae that made the original films so successful. While both centre on the same young woman named Julie (standing in as the younger version of the director), they cover two very different moments in her life. The first was her romance with an older man who met a very sad but self-inflicted fate at the end of the first film, while the second was about her experiences during the latter days of her film school journey, as she moves from rambunctious amateur to a fully-fledged professional in the span of only a few years. This film is primarily a bold manifesto to the artistic process – Hogg is not one for excess, and instead of making a film that revels in the joys and sorrows of the world of filmmaking, she avoids convention almost entirely, constructing a film that is as riveting as it is extremely simple. Mostly composed of episodic moments in the life of the main character, who is trying to find her voice as both a young woman in post-Thatcher Britain, and as an artist in a world that is still oddly apprehensive to accepting female perspectives as not only valid, but also interesting. It’s a deeply personal work, and Hogg ensures that there is something of value in nearly every frame of the film, particularly in how she presents such a different perspective on the creative process, showing her experiences with the fact that, while some may be born with raw talent, one doesn’t immediately become an artist, but rather have to develop and nurture their skills, which is essentially the foundation of what Julie experiences throughout the film, reflecting the director’s own artistic upbringing, which is presented with such authenticity and candour throughout the film.

Nourishing and building on existing merits are not only themes present in the development of the main character, but components on the creation of the film itself, which exist in direct dialogue with the previous film. The two works were not made too far apart, with only about a year or two dividing them in terms of when they went into production, but The Souvenir Part II is certainly a more mature project in terms of the kind of subject matter it is exploring, which is analogous with the story being told, since the narrative revolves around the gradual growth of the man character, who is transitioning from wayward college student to a fully-formed artist, all on her own merits. She is navigating some of the more challenging parts of early adulthood, and being forced to confront a number of very intimidating situations that most face to face in the journey towards maturity. Coming-of-age tales normally focus on younger protagonists, but considering how deep her perspective was in exploring Julie’s journey, The Souvenir Part II can certainly be categorized in much the same way – the character’s gradual realization that everything is not what it seems, and that she can’t take advantage of her sheltered, patrician life for much longer, is very similar to the traditional “educations” experienced by those in more conventional coming-of-age stories. Hogg is working through her own personal history in the construction of the film, so while we can certainly understand the perspective that she was looking at her past through the lens of rose-tinted glasses, the more challenging approach to the material indicates that she did genuinely want to make a film that had something to say, even if it takes a short while to actually get to that particular point – it helps that the film itself is incredibly compelling, even beyond the deeper psychological components drawn directly from the artist’s own experiences.

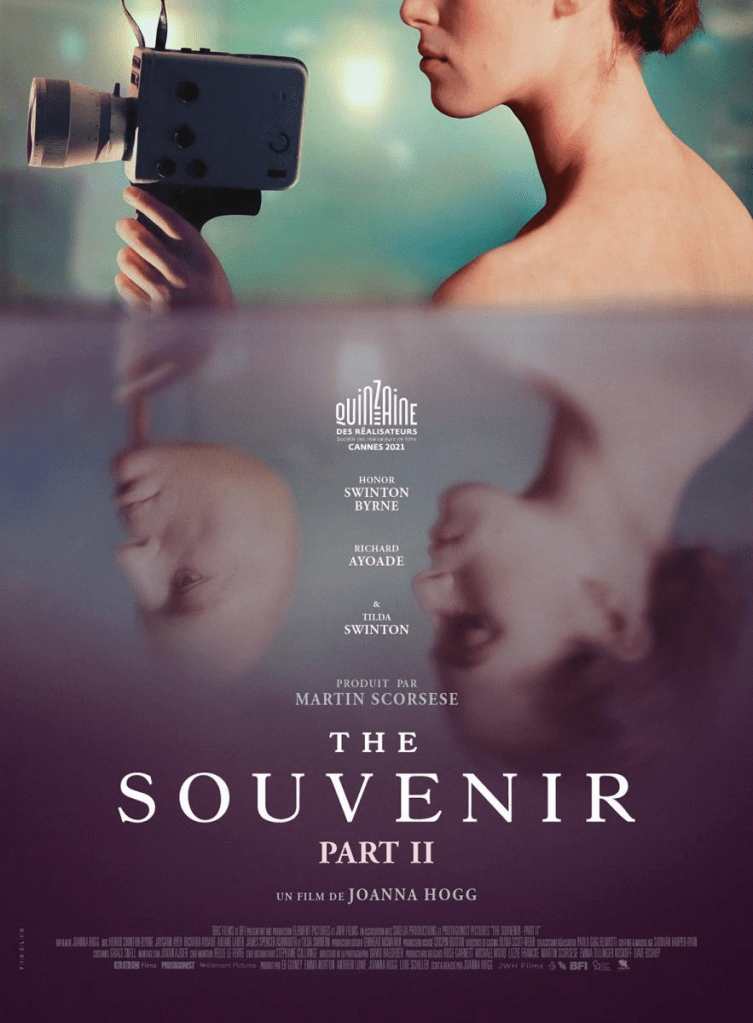

As was the case with the previous film, The Souvenir Part II sees Hogg once again casting within her own circle of friends and close collaborators, namely in the form of Tilda Swinton (who very likely inspired the character play by Ariane Labed in this film), and her daughter, Honor Swinton-Byrne, who steps into the part of Julie, occupying the role of the young woman that Hogg creates as a surrogate for her own life. As usual, the performances here are impeccable – these are incredibly simple and straightforward performances, handcrafted through delicate collaboration between the director and her actors, who all seem to be on the exact same page when it comes to putting these characters together. Hogg has a very naturalistic style, so it would be a challenge if the actors were not on the same wavelength – mercifully, everyone involved in the film seems to have the same idea of how to construct these characters, even someone like Richard Ayoade (reprising his role from the first film, in which he had a brief cameo), who manages to put aside his more eccentric comedic personality to play the small but pivotal role as one of the protagonist’s old acquaintances to whom she has to turn for help. These characters feel like real people, being interesting individuals rather than mere archetypes, which ultimately helps the film in developing that very delicate but striking tone, which could only be achieved through a set of performances that are as authentic as the film that surrounds them – and casting people who the director knew was immediately a strong way of ensuring that her vision, whether resonant or not, came through in a way that felt genuine, rather than just being an assembling of great actors without roles that were worthy of their talents, which is often the case with films that look at this range of themes.

As a whole, The Souvenir Part II is certainly a compelling follow-up to a film that may not have required a further look in theory (since the first film was absolutely incredible all on its own), but one that we are certainly fortunate to be given the opportunity to visit again. Hogg’s decision to make this sprawling two-part existential epic in which she looks at a few years in her early adulthood in which she was finding her voice as an artist so enthralling. It only helps that some of her early short films produced during the era depicted in the film (such as Caprice, her first collaboration with Swinton) have been plucked from the archives and made available to viewers – it makes watching this film so much more interesting, since seeing the accumulation of the various quandaries and challenges faced by Hogg’s semi-fictional construction rendered in a tangible product is fascinating, and leads us to wonder to what extent the events she depicts are identical to reality. It may not have the same raw energy with which its predecessor arrived and surprised viewers (being a small film from a director who was not known to most people, with the exception of those with some knowledge of the European arthouse), but it has a kind of peculiar charm that comes through in the enormously intense narrative that touches on issues surrounding identity, humanity and the role our environment plays in defining us as human beings. It’s a wonderfully unique film, and concludes Hogg’s duology on an absolutely impeccable note, allowing her the chance to narrate her life on her own terms, drawing on the theme of memory (which are presented as a number of souvenirs in the main character’s life), supplementing the themes of the first film and adding several new ones, which accumulate in this stunning and profoundly moving existentialist drama.