Somewhere in the English countryside sits an idyllic hamlet, on which Nutbourne College stands. A prestigious boys’ school that has been operating for decades, it has been known to produce a high calibre of students, which can easily be attributed to the strong, willful headmasters who occupy the intimidating post at the helm of the school. Unfortunately, Wetherby Pond (Alastair Sim) is not one of them. A meek milquetoast of a man, he prefers to spend his afternoons with a nice cup of tea rather than doling out punishments to rebellious schoolboys or asserting his authoritarian powers on his staff. The new school year offers very little by way of changing his opinion, until he receives the sudden and disconcerting news that Nutbourne College will be visited by St Swithin’s Girls’ School, another private academy that requires their premises for one day and one night, as their campus is not yet ready for the students’ return. They’re led by the terrifying Mrs Whitchurch (Margaret Rutherford), who is the exact antithesis of Pond – a stern disciplinarian who rules over both her staff and students with an iron fist, she is not used to being challenged, but certainly does encourage anyone to try. The two school-heads are instantly at combat – not only are they fighting for the honour of their respective academies, but also to determine which of the two sexes will emerge triumphant, especially when they’re both faced with obstacles that somehow put them in opposition, while requiring them to somehow work together, all of which leads to them determining the answer to the age-old question: what is the superior sex?

Films that focused on the differences between men and women, normally positioning them in contrast to one another, were wildly popular for several decades during the height of the classical era of filmmaking (and they still linger, albeit in a far less binary, direct form). The stories, often referred to under the term “the battle of the sexes”, had a very particular place in the history of literature, often being the source of some of the funniest and most insightful satires of their era, prior to the rise of second-wave feminism. The Happiest Days of Your Life is one of the many entries into this sub-genre that actually manages to be quite insightful about the specific commentary it is making, combining it with another wildly popular sub-genre, that of the “schoolyard comedy”, which found their home within British cinema for several years following the end of the Second World War, where directors and writers would you the innocence of children in their inevitable habitats of private schools to comment on broader issues – some of them certainly more serious than others. Frank Launder, a director whose name is often recognized alongside many of the more cherished but commonplace British comedies of the era, took quite a peculiar story and turned it into an absolutely riveting, insightful comedy-of-manners that is frequently funny and always well-executed, the result of a career spanning into the 1930s, from where the director learned many of the simple but effective skills that grounded his work and made him such a compelling voice in the early, formative years of British comedy.

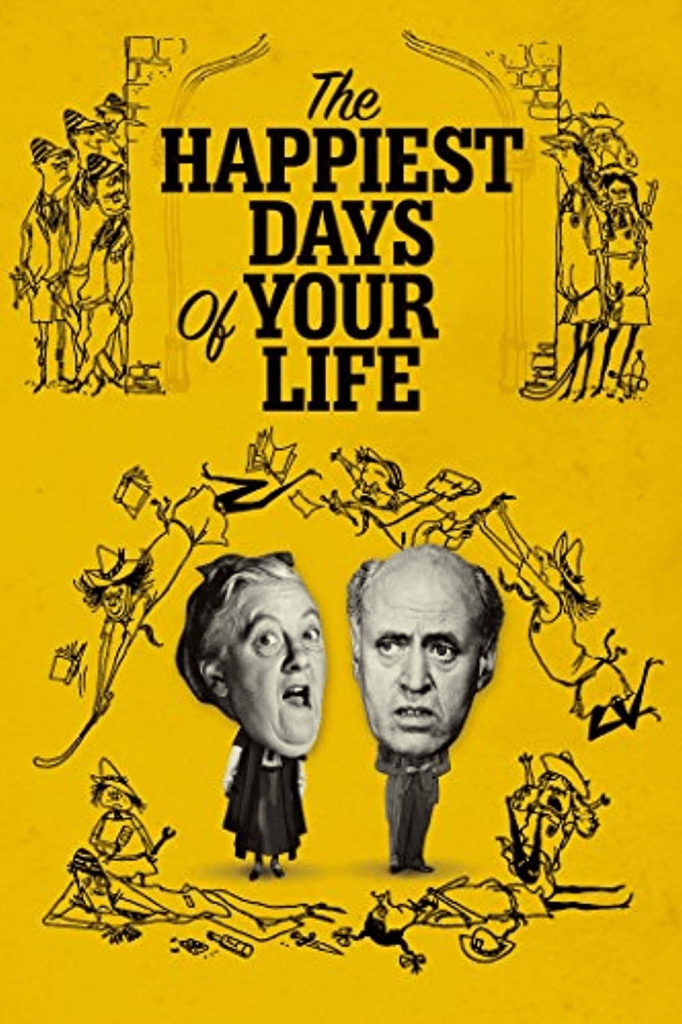

As one would expect, The Happiest Days of Your Life was built on the names of its two central actors, both of whom were considered amongst the finest actors Britain had to offer at the time. The notoriously prolific Alastair Sim lends his talents to the role of Mr Pond, the meek headmaster of the boy’s school who has very little interest in anything other than a peaceful existence, while Margaret Rutherford, who had conquered stage and screen throughout her career, was Mrs Whitchurch, the scheming but principled headmistress of the girl’s school, who suddenly emerges as what appears to be an obstacle to the frustrated Pond. The two actors are incredible together, their chemistry absolutely sensational, to the point where it becomes almost staggering that this was the first time these esteemed character actors had worked together (with the exception of Rutherford having a minor uncredited part in the 1936 mystery film Troubled Waters, where she and Sim didn’t share any scenes together), since they not only feel so perfectly at ease with one another, but are able to supplement their co-star in a way that feels purposeful and meaningful. This is the impact that great character actors have – they aren’t only chameleons in terms of disappearing into a wide range of roles, but can adapt to working with nearly anyone, granted the material is there to facilitate such a meaningful collaboration. They may be playing archetypes that are riffs off characters they normally portrayed – Sim is the frazzled, scatter-brained intellectual, Rutherford the no-nonsense, stately martinet that demands the utmost obedience – but as was often the case with these simple comedies, there was very little need for either actor to extend themselves too far beyond what they were used to, since they contribute to the distinct nature of the film around them by playing these familiar but nonetheless captivating roles.

The Happiest Days of Your Life is not a very complex film, but it’s in this particular simplicity that the story manages to be quite compelling. A perfect representation of how keeping a narrative as straightforward as can be allowed, and instead giving the more peripheral elements of a film to be the subject of experimentation, this film is 80-minutes of unhinged entertainment, perfectly facilitated by a director who was extremely used to making such films, almost to the point where it was second-nature to him. Much of the success depends on the screenplay, which was written by Launder in collaboration with John Dighton, who weaved together a terrific story that exudes wit and sophistication, which contrasts sharply with the fact that the central plot is one deeply rooted in well-meaning vulgarity. The contrast between the two is the source of much of the comedy that makes The Happiest Days of Your Life such a delight – the final act is dedicated entirely to two concurrent visits by different groups of individuals, each one under the impression that they’re visiting either a boy’s school or a girl’s school (depending on the headmaster with whom they are liaising), and while it may require some suspension of disbelief, it’s foolish to consider it anything less than absolutely thrilling, since the sheer absurdity of the project leads to some absolutely hilarious situations that should not be taken for granted just because they appear conventional. The Happiest Days of Your Life is a film that appears simple at first glance, but actually proves to be surprisingly layered as it progresses – and yet it never once loses us, instead adhering to a strict code of comedic conduct that works favourably in telling this hilariously irreverent story.

It may not be particularly well-known or acclaimed outside of a core group of experts and enthusiasts who align themselves with classic British comedy, but The Happiest Days of Your Life is nonetheless a total delight, a peculiar and hilarious comedy-of-manners that is filled to the brim with well-meaning humour and a lot of heart, which is often all one should expect from such films, and ultimately everything we require to enjoy these lovable, roguish tales of the middle-class malaise, which are formed into these delightfully upbeat stories that hinge less on a particular message, and more on the easygoing atmosphere that they evoke, and which sets the audience at ease. The aftermath of the recent war made films like The Happiest Days of Your Life all the more necessary, since they presented familiar actors in lighthearted comedies designed to distract and soothe the over-active postwar mind, which isn’t something that is often the source of praise when looking at such films, which are more frequently cited as buoyant but inconsequential diversions from reality, rather than well-formed works of art in their own right. Perhaps reading too deeply into it is counterproductive to the intention of the film, but it’s difficult to not view this as a product of its time, a delightfully sweet and endearing comedy with a lot of heart and an even wide abundance of wit, which is sufficient in setting us at ease and allowing this film to honour the ambitious meaning of its title, rendering it unexpectedly true, even if only momentarily.