Whenever a film is released that is vaguely questionable or perverse in either the story it tells, or the specific execution, there seems to be a concerted effort to rationalize it by comparing it to the work of some established provocateur, almost as if this helps give credence to the fact that someone has made a bizarre and polarizing film that stretches the boundaries of decency. Two of the most common names evoked in these discussions are David Lynch and David Cronenberg, two directors who are mostly very different in their styles and specific narrative curiosities, but do share the same penchant for artistically-motivated provocation. It seems that whenever a film that either doesn’t fit within the realms of logic, or functions as a more grisly effort to court controversy, one of these two names are evoked, with the similarities between their work and supposed pale imitations being tenuous at best. However, this brings us to the subject of Fresh, which is perhaps one of the few instances where we were not only seeing someone effectively mirroring their style (albeit in a very creative way), but somehow combining both of them. The directorial debut from Mimi Cave is a daring and absurd film that exudes the grotesque brilliance of early Cronenberg, and the polarizing satire of late-career Lynch, with a healthy dose of manic humour thrown in for the sake of making sure we understand that this film is a satire. Bizarre but effective, and consistently pushing the boundaries of decency without actually crossing the moral event horizon (at least not to the point where the film is exploitative), Fresh is a peculiar curio of a film, a strange and disquieting dark comedy that seems to have some very odd ideas embedded deep within its fabric.

Not since Eating Raoul have we encountered a film that so prominently prioritizes itself around being a cannibal comedy, taking one of the most taboo subjects in the history of civilized culture and weaving it into an irreverent and darkly comical satire. Logically, based on this detail, it should be expected that Fresh will be extraordinarily macabre. Cave chose quite an ambitious story to serve as her feature-length directorial debut, so one has to admire the sheer gall it took to emerge onto the scene by putting together something so unabashedly violent and grotesque, forcing us to immediately pay attention to her work. There are only a few films that can be intentionally grotesque and still seem charming, and Fresh is certainly one of them – it may have its imperfections, but there’s a certain admirable quality to how Cave (alongside Lauryn Kahn, who wrote the screenplay) balanced tone and content to form something unforgettable. It’s very clear that this film was not meant to be taken seriously, and the sooner we can abandon logic and just realize that this is an absurd and nonsensical story of lust that uses the consumption of human flesh as a means to provoke thought and repulse the viewer, the faster we can appreciate the genuine acts of rebellion that pulsate throughout the film. It’s not the first film to use the shock value of cannibalism as its primary selling point, but it’s certainly one of the few times it was used to such an oddly captivating degree, with the absolute disgust we feel being undercut by the genuinely jagged tone that sometimes leads us astray, to the point where the romance actually starts to make sense, albeit as a way of further extracting the pure madness from the reprehensible acts with which the director punctuates the film.

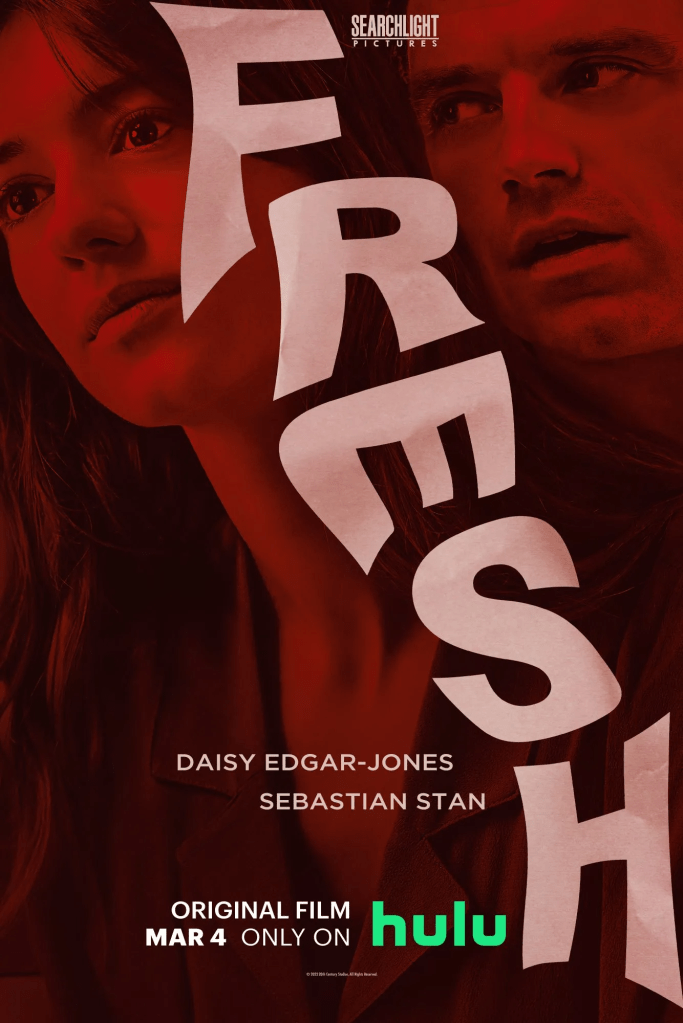

Considering the depth of perversion and unconventional desire that propelled the film, it makes sense that Fresh would need to put in a lot of effort to not be seen as merely a violently blood-stained satire without any depth. Much of this comes through in the performances, which are almost too charismatic in comparison to the very bleak nature of the film – and the duality between the two leads is part of what makes Fresh so peculiar. Daisy Edgar-Jones is steadily becoming a very reliable actress, and while her body of work is certainly small at this point, her performance here indicates that she is a formidable screen presence, someone that can carry a film like this without needing to resort to hysterics. Instead, that particular role is occupied by Sebastian Stan, who is finally given the chance to put aside his more heroic characters and play someone who is a lot more off-the-wall and bizarre, playing into his gift for finding the eccentricities in all of his characters, but which were previously only marginal. Despite its very dark subject matter, Fresh is a romance in a very perverted way, so there could not be a moment where we didn’t entirely believe in the chemistry between these two actors – the film doesn’t adhere to the rules at any point, so the responsibility to give it some semblance of logic was restricted to the actors, who provide strong evidence to being some of the most unexpectedly inspired performances of the year so far, with their total commitment and ability to pull together a strong and layered set of moments that are perhaps even better than the film that surrounds them.

Fresh is a film that may be a bit rough around the edges, and while it is a lot of fun from beginning to end, there are a few elements that point towards it being a debut. The tone is inconsistent, and it is never entirely sure of the exact approach that needed to be taken to ensure that it felt natural (although it’s not common for a comedy about cannibalism to ever be considered subtle), with the shift between genres being quite bewildering. However, this is all part of the experience, since the jarring humour and over-the-top violence is exceptionally entertaining when placed alongside one another. There is an argument that has been made that Fresh is mindless and inconsistent, and that its approach is far too incomprehensible to make sense. Yet, it doesn’t seem like it’s constructive to expect a film like this to be a hard-hitting analysis of people with sordid desires, but rather an over-the-top satire that plucks every bit of logic out of the story and ventures into the territory of being profoundly disturbing without losing the audience along the way. The film never takes itself seriously (how else can we explain the climactic scenes including a highly-stylised dance sequence, one of a few that can be found scattered throughout the film?), and therefore the audience should not be expected to see this as anything other than a wickedly deranged dark comedy that has its imperfections, but doesn’t allow itself to be weighed down by them.

It takes a lot of effort for a film to appear this demented, and while it isn’t the most scathing or interesting satire, it has a clear set of ideas that make for a vibrant and entertaining psychological horror with many moments of outrageous humour. One could argue that Cave went too far, while others may believe she didn’t go far enough – but considering the final product, it seems like there was a lot of effort to strike the perfect balance between genres, meaning that the intention of this film was to make the viewer uncomfortable rather than completely alienating us. It’s edgy and subversive, but also accessible for those who can handle some carefully-curated gore. It’s over-the-top but never excessive (at least not in a way that can be considered immoral), and it has some bold ideas, some of which remain clearly conceptual, while others flourish into some unforgettable moments that occur throughout this film. Darkly comical and creatively nauseating, Fresh is a fascinating experiment that proves that even the most disgusting of subjects can lead to an unconventionally brilliant romantic comedy, which is not something that one would necessarily expect, but its difficult to not respect the audacity to actually tell this story – and regardless of how one feels about the specific details, Fresh certainly does leave a peculiar taste in one’s mouth.