It’s sometimes difficult to hold an opinion contradictory to the vast majority on a particular film – the feeling of being isolated from the general opinion can feel quite alienating, especially when it comes to films that have been cited as sacrosanct classics. To date, I have yet to find someone who holds the same opinion on A Streetcar Named Desire that I do, which is that Elia Kazan’s adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ achingly beautiful manifesto to a generation lost between the two wars is an enormous disappointment. Perhaps not a bad film, but rather one that is merely adequate at its best, hopelessly dull at its worst, there’s something quite bewildering about how this film has been celebrated, especially at a time when Hollywood was putting effort into many stage adaptations, several of them produced in the 1950s rising to the status of being some of the best of that particular era. Middling in the way that a run-of-the-mill melodrama tends to be, and lacking the spark that made Williams’ original text such a deeply personal and insightful glimpse into the world as he saw it, A Streetcar Named Desire rarely rises to a place where it can be considered all that entertaining, with the dour emotions, inability to set a consistent tone and jagged quality of performances leading it to be quite unstable, almost as much as the mental state of the protagonist, whose journey we can never truly invest in as a result of the often disconcerting approach taken by Kazan, whose workmanship was not operating at its peak when producing them film, leading to a needlessly heavy and often exceptionally convoluted drama without much merit outside of a few moments where some promise shines through the ersatz emotions.

Melodrama is a challenging genre, since it is just as easy to succeed as it is to fail when working within it. Williams was one of the forefathers of what is referred to as Southern gothic, a branch of the genre that sees these fascinating stories unfolding in areas south of the Mason-Dixon Line. The combination of traditional conservative values with more intense cultural traditions indigenous to these locations often make for rivetting stories, and considering the playwright himself hailed from the area himself (strangely enough from Mississippi, rather than containing the Appalachian roots suggested by his nom de plume), there has always been a lot of merit in his perspective. It’s difficult to say Kazan squanderd the promise contained in the original play, since Williams himself collaborated with the director (and Oscar Saul) on this adaptation, aiding in the writing of the screenplay. Honestly, the writing isn’t the problem – the dialogue is filled to the brim with the carefully-curated poetry we would expect from Williams’ writing, and it is also beautifully calibrated to convey a particular set of deeper discussions that are sometimes more complex than we’d initially expect based on the premises. This is all very positive, and part-and-parcel of the success that surrounds this film – it’s the less-obvious moments that take us by surprise, which do lead to the film being somewhat worthwhile in how it views issues of mental health, marital strife and a range of other themes. The issue comes in how Kazan adapts the material – it just never seems to be amounting to much, functioning as several loosely-connected scenes following the lives of characters from slightly different backgrounds, and if varying temperaments. This should be fertile ground for a gripping and enduring work of drama, but unfortunately Kazan struggles to leave much of an impression, despite having a strong set of guidelines in the form of the original play, which already did half of the work in terms of establishing a structure and tone.

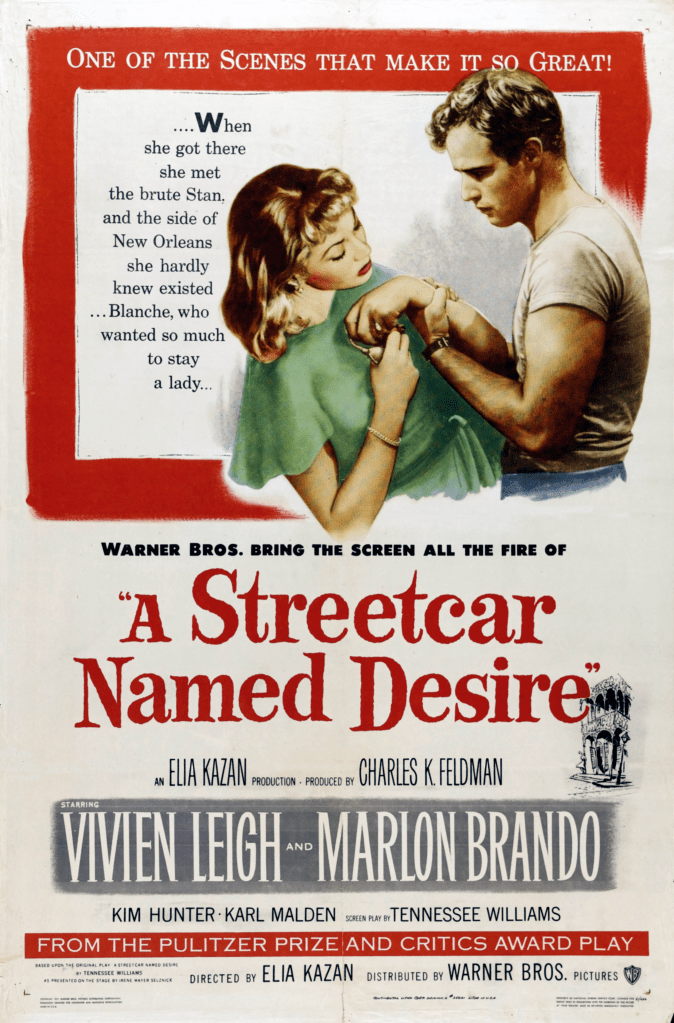

Perhaps my most controversial opinion surrounding this film has to do with the aspect that is most celebrated – when it comes to film performances in the 1950s, Marlon Brando and Vivien Leigh in A Streetcar Named Desire are often cited as some of the most impressive. This isn’t a difficult opinion to understand, since they are both certainly doing a lot of acting – the problem is, not all of it is very good. The problem with this interpretation of the play is that the central quartet are all very gifted actors, but they’re all working at different levels, and pitching their performances in various ways. This is most noticable in the disconnect between Leigh and the trio of Brando, Karl Malden and Kim Hunter. Interestingly, this disparity is likely the result of the latter three having originated these roles on Broadway (and thus spent a considerable amount of time developing these characters on stage, long before this film went into production), while Leigh was brought in instead of Jessica Tandy, whose version of Blanche DuBois is almost legendary within theatre circles. No one is necessarily bad in A Streetcar Named Desire, they just seem to lack the same idea of where this story is meant to go. Leigh in particular struggles the most – her performance doesn’t feel like its coming from someone who is often cited as one of the greatest actresses of her generation, a performer who turned in what many consider to be one of the finest portrayals in stage history in the historically-important Gone with the Wind. In this film, her attempts at vulnerability are rendered as wide-eyed confusion, her moments of subtletly coming across as forced, every cog used to give this performance unfortunately present in each scene. This is a role that demands a degree of theatricality, which Leigh delivers. However, its in the more quiet moments that are just as important that she seems to falter, which is unfortunate considering how Blanche is a vitally important role in the history of theatre, so to have the most prominent interpretation mired by a relatively lacklustre performance from an otherwise very gifted actress seems unfortunate.

Like my mixed feelings about Leigh’s performance, much of what I found troubling about A Streetcar Named Desire resides within the minority opinion. Expecting too much from a film that has supposedly been preordained as a classic is sometimes foolish, since it leads to disappointment – and there is just something so off-kilter about this film, a quality that doesn’t quite compute with its status as some unimpeachable masterpiece, and which keeps the viewer at arms’ length, never quite allowing us to engage effectively in what is supposed to be a very profound story. Personally, the emotional content felt too abstract to be entirely successful, the overwrought approach to conveying the commentary at the heart of the story feeling as if Kazan was going too far, doing away with every bit of subtletly that should govern a film like this. Translating the story from stage to screen brings with it an entirely new world of opportunities, and a good filmmaker would take advantage of the chance to expand on the world of the play, but to the point where it is subtle and very nuanced. Kazan goes the opposite direction – a bigger stage demands bigger emotions, and nearly every component from the original play is inflated to the point where it sometimes borders on parody. The camera lingering too close on Leigh’s wide-eyed ruminations, the shoddy camerawork trying to capture every detail (and in the process losing the more simple beauties contained in Williams’ dialogue), and the constant shuffling to and from locations causing the story to feel too frenzied. At the heart of all these issues is the inability for the film to pay sufficient tribute to the very emotional intentions that drove Williams to write this play in the first place – and while it’s easy to fault Kazan for the challenges in the adaptation process, it feels like the troubling aspects of the film are a result of a collective decision to go too far, without the necessary ability to reign the hysterics in when it was most required. A Streetcar Named Desire is a film I have periodically revisited, especially in my frequent attempts to get on-board with the absolute adoration that has been asserted on this film for as long as it has been embraced by viewers. However, I’m reminded every time how it just isn’t a film that works for me – the brand of melodrama doesn’t quite register as all that enthralling, and the performances aren’t captivating enough to hold my attention. There is nothing inherently bad about this film, with all the components that many have admired about it being very clear, just not rendering themselves as all that impressive, being servicable at best. As a drama focused on some very deep themes, especially inciting discussions about issues that were extremely ahead of their time (but which also had to fall victim to the stringent production codes, which meant a lot of Williams’ original ideas and details embedded in the play are elided to satisfy the conservative values of those who unfortunately yielded too much power in determining what was palable and appropriate for audiences at the time), there is a lot of merit in A Streetcar Named Desire, it just happens to be under two hours of overwrought storytelling that takes too long to get to a coherent point, and the ambigious character motivations don’t do it any favours either. As a whole, the high praise asserted on A Streetcar Named Desire is understandable, but still somehow hyperbolic – it’s a conventional drama with some fascinating ideas, but one that barely registers as a shadow of its source material, which was so much richer and more evocative than this interpretation, which falls short of being a worthy adaptation far too frequently for it to be considered excusable.