The Browning Version is a text written for everyone who has regrets, especially those relating to never putting in the effort to fit in. Terence Ratigan’s fascinating drama has been celebrated for its raw understanding of the human condition, as facilitated through the story of an ailing schoolteacher who realizes in his final days before his forcible retirement the true scope of his poor methods of education, and feverishly tries to mend whatever long-last damage he has caused over his three decades of teaching – but these efforts may seem futile, since it’s not particularly easy to convince those who have been conditioned to one’s behaviour to believe that a leopard can easily change its spots. The wonderful Anthony Asquith, who frequently worked to adapt acclaimed pieces of theatre to the screen, brings Ratigan’s story to life in this film, creating one of the most unforgettable and humane dramas of the 1950s. Beautifully elegant and simmering with the most potent of emotions, The Browning Version is an incredible achievement – simple but effective in the way only the strongest literary adaptations tend to be, and anchored by one of the most impressive performances of the decade, the film is remarkable, especially in how it balances the several complex emotions that reside right at the heart of the story. As one of the most intricate and moving explorations of personal identity produced at the time, The Browning Version is simply exquisite, and earns its place in the canon of genuinely profound stories of the human condition, all through Asquith’s absolutely astonishing prowess at adapting this play.

Teachers have often been represented well on film – from Goodbye Mr Chips to Dead Poets Society and everything in between, there is a long culture of inspirational stories of educators using their skills to make a difference in the lives of their pupils as they venture off into the uncertain future. Of course, there are a few that look at teachers who are less than ideal, which is a perfectly apt description for The Browning Version. The character of Andrew Crocker-Harris is a complex one – he’s not a necessarily poor teacher by ordinary standards, since he does his job and is always dedicated to giving students an education, as per his responsibility as a veteran educator. However, it’s his methods that are called into question, with his droll style of teaching in class, and his stern and unapproachable demeanour outside of it, making him a figure of considerable scorn by students, parents and faculty alike. However, The Browning Version is not dedicated to completely disparaging the character, as he is the central figure of this story, the person we follow as he slowly realizes how he has wasted his career being a strict and unforgiving master, without realizing the impact it had on those around him. There’s a fine line between portraying Crocker-Harris (or “The Crock” as he is affectionately referred to by his peers and students, albeit behind closed doors) as either a villain or a misunderstood curmudgeon, and a massive part of this film comes from the director managing to find the right way to navigate this narrow boundary. Needless to say, the final result is absolutely spellbinding – a sophisticated but meaningful character study that presents us with a complex protagonist, but is never too unforgiving in its assessment of his flaws, giving the character the opportunity to develop into one of the most unexpectedly tragic heroes of the period in which his story was told.

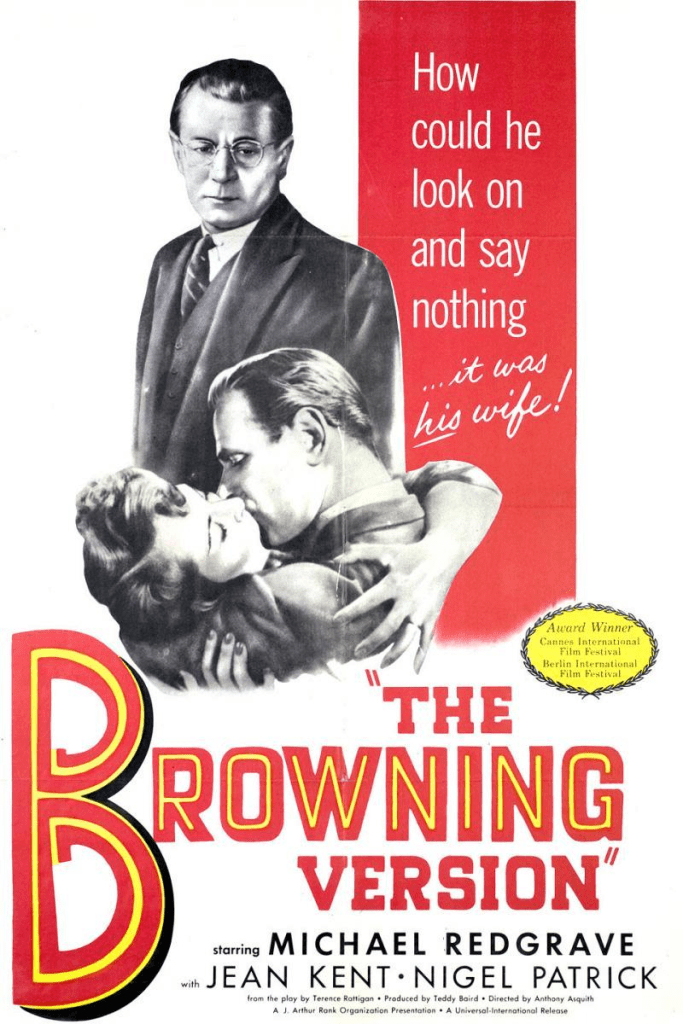

The Browning Version has been adapted many times across every possible medium that allows for a performance of some kind – and while every adaptation varies in how it approaches Ratigan’s text, something they all have in common is the emphasis placed on the actor portraying Crocker-Harris. This is a role that is coveted by many actors (particularly those of a certain age), but which very few get the opportunity to play, at least successfully. This version of the play features perhaps the definitive interpretation of the character, by way of the astonishing Sir Michael Redgrave, who turns in one of the greatest performances of the 1950s. As a renowned thespian, it should be no surprise that Redgrave turned in a great portrayal – but this is only the beginning of what can be described as one of the most heartbreaking demonstrations of raw humanity ever given by an actor. His brilliance is impossible to overstate – he never makes decisions that can be considered too bold or brash, and he keeps everything very internal, never once raising his voice to the point where it could be considered as chewing the scenery (which is unfortunately a common tendency for such characters, many actors struggling with the more intimate aspects of such roles). He finds the nuance in every moment, drawing out the most intricate details that not even Asquith could’ve pulled out through his direction – this is a clear case of the “actor as auteur” theory, where a performance is built from the dedication an actor has to finding the voice of the character, and developing it through his own interpretation. It’s an astounding performance by an actor who rarely receives the praise he warrants, with this being perhaps his most impressive performance, which is a bold statement considering how deep and varied his career was on both sides of this incredible film.

There are several moments in The Browning Version that are amongst the most emotional of the era – Ratigan’s original play is not one that aims to be as stoic as its protagonist. Yet, there isn’t a single moment in this film it feels heavy-handed, even when it is at its most dramatic. Most of the conflict is drawn from the very internal process undertaken by Crocker-Harris to reflect on his own past in the final days before he leaves the school that he considered his home for decades. It deviates from other memory-based stories by never allowing the main character to dwell too long on the “good old days”, since the general theme that guides the film is that he seeks to suppress years of unsmiling, indifferent apathy as he realizes that a good teacher isn’t only one that can teach a subject well, but shows compassion and kindness to his students. This is a beautifully introspective film, but it has many challenging moments as the main character reflects on his past behaviour and yearns to correct it, even if he knows it is impossible. The film never positions him in such a way that he radically becomes the epitome of charm and exuberance (which a more cliched film may have done), but rather showcases the small, almost inconsequential, changes he makes. It leads to the stunning climax, where he delivers a passionate speech to his soon-to-be former pupils and colleagues, where he sincerely apologizes for his past actions, and states his outright regret at never having put in the effort necessary to be a good teacher. The Browning Version is filled with moments of gentle reflection on the part of the main character, who is far more complex than those around him would lead you to believe – and through capturing these raw moments, Asquith creates something absolutely unforgettable, using Ratigan’s gorgeous text as a guideline to tell this astonishing story.

The Browning Version is a fascinating film about looking to the past and trying to reconfigure our approach to how we interact with others, which can be a massively difficult if those days were filled with regrettable actions. It can sometimes be quite a difficult film to watch, especially when the director is attempting to cut to the core of this complex protagonist as he grapples with conflicting feelings of regret over his previous approach to his career, and the knowledge that regardless of how much he tries, he will never be able to get those years back, and that the only option for redemption is to try and change going forward. It conveys a message but never preaches or becomes overwrought, an important distinction for a story that could’ve very easily have been a cliched jumble of misguided emotional sensations that don’t amount to anything. On all levels, The Browning Version is a very impressive work of narrative storytelling, using a complex protagonist as the figurehead for a deep and insightful series of discussions, whereby the most intricate aspects of the human condition are prodded and provoked to incite some rivetting conversations around the importance of being earnest and honest, both to oneself and those to whom they have committed their livelihood. Intimate but powerful in the way the most impactful dramas from this period tended to be, The Browning Version is absolutely stunning, and through excellent writing (which takes a few liberties in expanding Ratigan’s world) and one of the most thoughtful and layered performances of the era, Asquith and his collaborators created something truly special, a film that lingers on, not only in terms of the story, but the emotions embedded deep within this disquieting but beautiful version of the world and the people who populate it, which is also dependant on our own interpretation.