With the Academy Awards being held this evening, it brings us to our annual tradition of reviewing the past year in film. 2021 was certainly a tumultuous year when it came to cinema – while caution was still taken in terms of how films were released (with many distributors offering audiences the chance to see their films from home a lot earlier than they normally would in a traditional year), we also saw some semblance of normality gradually emerge, with various major film festivals gradually assimilating back to in-person attendance, and many films having their theatrical releases as planned. Cinemas reopened, and many of us flocked to once again feel the magic of sitting in an audience and sharing that experience with other viewers. Needless to say, the past year was one that was full of obstacles, but it was also one where we could feel that life was slowly returning back to normal, or at least starting to get to that point.

In terms of the actual films that were released, we were certainly spoiled for choice. Whether it be major blockbusters or more artistically-minded fare (or some films that occur at the perfect intersection between the two, of which there were many), there was something for everyone. Globally, we saw recognition for some of the industry’s best auteurs, and a few of our most cherished film icons reminded us of their unimpeachable genius. Diversity was once again a pressing issue, albeit one that has continued to show further signs of becoming conventional – as of writing, all of the incumbent recipients of the top prizes at the three major film festivals are held by films directed by women – Titane by Julia Ducournau (Cannes), Happening by Audrey Diwan (Venice) and Alcarràs by Carla Simón (Berlin). While two of these will only be eligible for next year’s list, based on their release, it still warrants mentioning that we are in an era where a broader range of stories can be told. This extends beyond gender – geographical boundaries are not only being crossed, they’re outright being deconstructed as audiences engage with a broader range of films from a wider set of voices from every conceivable demographic. Needless to say, the past year proved that, when given the chance, these filmmakers are capable of providing the most incredible and vivid art, which has made seeing their films such a pleasure.

Like any given year, 2021 had its fair share of successes and failures, both of which are important to acknowledge – however, today is one spent celebrating the best cinema has to offer, and this year did provide more reasons than ever to be in love with the movies. Whether watching from home or venturing out into the cinema and sitting amongst friends and strangers, we all consumed a wide range of artistry, experiencing different worlds and sensations that come along with it – now more than ever, we are engaging with a wide range of emotions. The world is falling apart, and artists are doing their part to hold it together – and whether offering a momentary diversion, or expanding on the many issues that face our world, cinema has undeniably evolved into one of the global languages, many of these filmmakers being well-aware of the power and responsibility offered to them. 2021 was an incredible year for film, so let’s celebrate a few of the best that the past few months have had to offer.

Without any further ado, here is the list. As usual, we’ll start with a few honourable mentions before jumping directly into the films that best embodied the previous year in cinema.

Honourable Mentions

Barb and Star Go to Vista Del Mar

Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)

The Best Films of 2021

If we are discussing the idea of art shattering boundaries, we simply can’t ignore Limbo, a film that celebrates the very idea of defiance. The small independent comedy has been seen by much fewer people than it deserves, but it remains one of the most endearing and sincerely moving portraits of life committed to film in recent years. The story of a young immigrant trying to find a better life in Europe, only to be faced with the challenges of being stuck in limbo, both physically and existentially, is one that we can all relate to on some level – and Ben Sharrock proves what a promising young director he is with this wickedly funny and gloriously heartwarming story of demonstrating resilience in the most unexpected ways.

When word first emerged that Joel and Ethan Coen would be temporarily splitting up after over 30 years of constant collaboration, the anticipations for what they would produce were incredibly high. Joel Coen’s efforts in adapting one of the most celebrated texts in the English language was met with a combination of scepticism and excitement – and the result is The Tragedy of Macbeth, one of the finest interpretations of William Shakespeare’s timeless text. Taking its cue from German Expressionism in terms of visual palette (with the gorgeous black-and-white photography capturing the simplistic but jagged production design), and featuring career-best work from Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand (both of whom we born to play these roles), and also one of the year’s best performances on the part of stage veteran Kathryn Hunter, this film presents a terrifying and brutally bleak portrait of Medieval Scotland, scaring the audience while simultaneously putting us in a state of total awe, all of which are fundamental to the success of this challenging and provocative reconfiguring of The Bard’s incredible story of greed, corruption and murder.

In The Power of the Dog her adaptation of Thomas Savage’s novel, Dame Jane Campion proves that she has not lost an iota of the ambition that made her amongst the most gifted filmmakers of her generation. Taking on a genre that is normally attributed to her male counterparts, as well as filtering the story through the lens of a scathing critique on heteronormativity, Campion is going in search of the myth of the idealistic American male, employing a stellar cast to bring to life these morally-ambigious and deeply complex characters that challenge the notion of masculinity and subvert expectations in a way that redefines how we perceive not only this genre, but the entire mythical space of the American West, which the direction carefully but meaningfully deconstructs to form this astonishing testament to the darker side of the human condition.

Teaching is certainly the profession that makes all other professions possible – and no one understands this better than Dieter Bachmann, who has used his decades as a teacher to make his classroom a sanctuary for students, who enter into those hallowed halls without any expectations, and leave it as individuals slightly more prepared for the outside world, a result of their teacher’s sincere passion for his craft. Maria Speth captures Bachmann in this incredible documentary, which spends a considerable amount of time looking into this veteran educator’s process, providing a vivid snapshot of a few months in the life of this classroom, which becomes a vibrant ecosystem of challenging conventions and debating traditions. Sometimes the most moving stories are those that are pulled from reality, and there are few films about the art of teaching more poignant than this one, which spends 220 minutes exploring one man’s journey to educating the future generation, which he has been doing for several years, and will likely continue doing fo several more, with his undying devotion to his craft making him an incredible and aspirational role model.

If someone was going to make a film about perverse nuns battling their sexual identity in plague-ridden Italy, it would be Paul Verhoeven. The quintessential agent provocateur of contemporary cinema, he has proven on countless occasions to be capable of venturing far beyond the limits of human decency in order to make films that are as riveting as they are demented. His version of the life of Benedetta Carlini (which features career-best work by the effortlessly gifted Virginie Efira and Charlotte Rampling) is a brutally funny exercise in shocking audiences with imagery and commentary that challenges our beliefs and forces us to reconsider the entire purpose of faith in the first place. The subject of protest from groups that expressed their horror at seeing the sanctity of religion represented in such sordid terms, Benedetta is a masterpiece of puritanical satire that dares to go further than many films would even consider viable, leading to an enthralling and deeply bizarre drama that proves that romance can be found in the most unexpected places.

Sometimes, the most effective and moving works come in the smallest packages. The follow-up to Céline Sciamma’s incredible Portrait of a Lady on Fire was always going to be layered with unreachable expectations – and in many ways, Petite Maman can be considered a much more minor work. However, this was entirely intentional – the quaint 72-minute gem combines coming-of-age drama with Lynchian fantasy to tell the story of moving through time and space, not for any other reason than getting the answers to the questions we haven’t even asked yet. Intimate and beautifully endearing, it’s difficult to not fall deeply in love with this film, which carries an emotional heft that contrasts sharply with its relatively small appearance, one of the numerous endearing quirks that make this such a special work of postmodern, stream-of-consciousness fiction.

The creative process has caused many a sleepless night, which is often the best-case scenario for several artists. This serves as the starting point for Bergman Island, Mia Hansen-Løve’s semi-autobiographical drama that centres on two filmmakers venturing to the island of Fårö, which was known to be the main residence and final resting place of Ingmar Bergman. Through looking at the lives of artists through the lens of a strained marriage, the director manages to tell a profoundly moving, and often achingly beautiful, story of finding oneself through the process of leaving behind the weight of the past, and the insecurities that come with it. Grounded by stunning performances and gorgeous Scandinavian vistas, the film is a timely tribute to those who seek to break out of the monotony of life, and go in search of something much deeper.

In this gorgeous ode to motherhood, Pedro Almodóvar reflects on a number of fascinating themes, interweaving the story of two women that experience the indescribable joy of having children with a haunting story of Spain’s unsettling past, using the two disparate narrative threads as the foundation for a moving, complex glimpse into the lives of ordinary people placed in situations that are deeply complex. Filled to the brim with vibrant colour, poignant melodrama and exceptional performances (particularly from the beguiling Penélope Cruz, who once again proves that she is amongst the director’s most important creative muses), Parallel Mothers is an astonishing achievement that challenges conventions and goes in search of the answers to some of life’s more elusive questions.

Sean Baker has always had a knack for crafting meaningful stories set amongst working-class communities, and often employing the very kind of people depicted as the actors. Red Rocket is one of his strongest (and strangest) efforts, telling the story of an eccentric former adult film star looking to find his redemption by moving back home to his small quaint town in the heart of Texas, where he seeks forgiveness from those who were the victim of his bizarre ambitions. It’s a wildly entertaining film that is impossible to predict – every moment feels genuinely very strange and unexpected, and the story (which rarely makes sense) is incredibly enjoyable, at least in terms of commenting on the deep issues that define this film. Simon Rex gives one of the year’s very best performances, and his heart and humour are essential to the film’s success, which only leads to a vastly more compelling film, especially in the moments where it chose to be endearing when it could’ve just as easily have been exploitative, which is a decision Baker often makes when telling these wonderfully moving stories of everyday life in communities that are rarely afforded the opportunity to have their time on screen.

How do you find yourself when you don’t even know who you were to begin with? This is the question Pat Pitsenbarger asks himself on a daily basis – and when he hears that one of his clients from his days as one of Ohio’s finest hairstylists has died and has requested him to do her hair and makeup one last time as she sets off for the great beyond, he embarks on a cross-state journey, accompanied by his electric wheelchair and unimpeachable wit. Swan Song is an achingly beautiful film, the kind of endearing comedy that draws as many tears as it does laughs – and while it seems like a relatively minor effort as a whole, it carries itself with such incredible earnestness, it’s difficult to not fall deeply in love with what director Todd Stephens is aiming to achieve here. Whether it be the mighty performance by the incredible Udo Kier, or the astonishingly personal flourishes brought to the film by everyone involved in its production, Swan Song represents yet another stunning entry into the canon of genuinely profound films that touch on queer issues with heart and humour, and leave us both moved and entertained.

How do you condense an entire journey towards adulthood into only two hours? This is the question Joachim Trier asks throughout The Worst Person in the World, his deeply moving and incredibly funny dark comedy that captures the spirit of existence through twelve chapters (as well as a prologue and epilogue) in the life of a young woman caught in the awkward recesses of early adulthood. Through her interactions with various characters – including two diametrically opposed love interests with whom she manages to find the solutions to many of the answers she has been seeking, albeit not necessarily as a result of their positive qualities – she begins to learn the reality of everyday life, and how not everything is what it seems. The journey through life is filled with twists and turns, most of which can never be predicted. Ultimately, there is only one life, and even though we’re not able to pause it and gleefully run through the frozen city streets of Oslo, there’s always value in stopping and taking stock of reality as it gradually unfolds in unexpected ways.

Very often, we find that the most affecting works of art are those drawn from someone’s personal experiences. When Paolo Sorrentino (who has already established himself as one of Italy’s greatest filmmakers) set out to tell the story of his own childhood growing up in the Italy of the early 1980s, the result was the stunning and striking The Hand of God, in which the director addresses issues surrounding identity, family and burgeoning creativity, which coalesce into this gorgeous existential odyssey that takes us on a (meta)physical journey through Italy, set to the backdrop of a very particular era in the nation’s history. Made with compassion and precision, and featuring some of the very best performances of the year (such as veteran actor Toni Servillo’s scene-stealing work, as well as newcomer Filippo Scotti as the protagonist), The Hand of God feels like an immense achievement, the kind that really only comes around once in a lifetime, once again proving how Sorrentino is one of our greatest living artists.

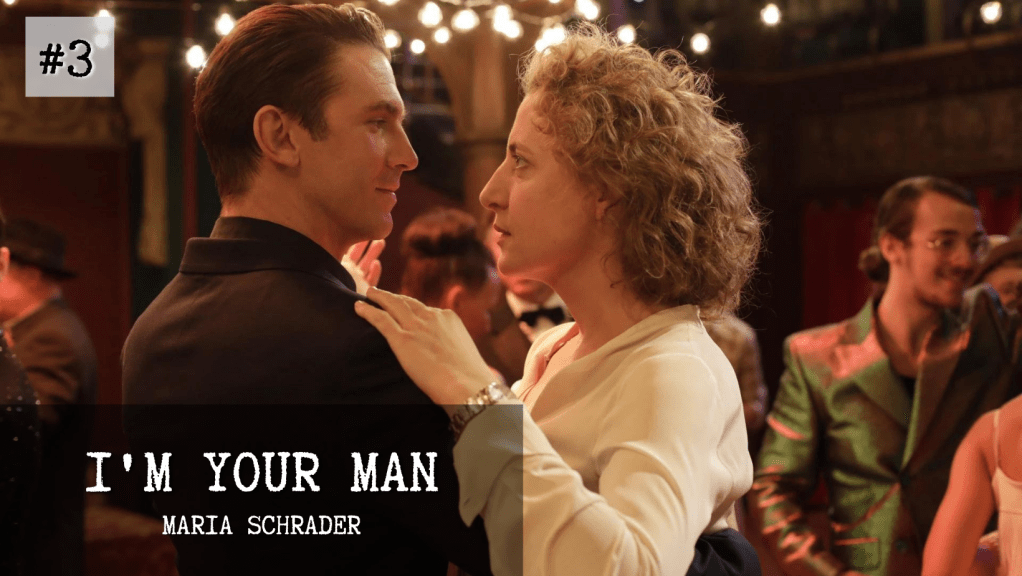

Is it not one of life’s great ironies that the most human film of the year focuses on a robot? In yet another entry into her steadily-growing canon of incredible directorial efforts, Maria Schrader tells the story of a lonely academic who finds love in the most peculiar circumstances, being given the chance to “test” a new form of artificial intelligence, which takes the form of the man of her dreams. I’m Your Man is a powerful film – it looks at the concept of life and death through the lens of eccentric dark comedy, which comments on how we are likely to find love in the future. It’s not the first film to tackle the subject of falling in love with an artificially intelligent entity, but it is one of the best. Featuring incredible performances from Maren Eggert and a never-better Dan Stevens, this film is an absolute delight, the kind of thought-provoking comedy that can incite as much laughter as it can discussion, which is not something that the director seems to be interested in neglecting, leading to this absolutely beautiful and striking work of socially-charged, philosophically-profound romantic comedy.

There are a multitude of ways to describe Ryūsuke Hamaguchi’s Drive My Car, a film that is as ethereal as it is dense, but in the most admirable way possible. Telling the story of a widowed theatre director who discovers that he is slowly going blind, the film is a brutally honest and often profoundly heartwrenching meditation on the nature of existence, and the volatility of life. Many people tend to view life as a journey that ventures down a long, winding road, filled with various obstacles that can’t always be seen from afar – and the recurring motif of transit is not accidental in this regard, the director constantly drawing on the tedium of everyday life and placing it in stark contrast with ruminations on the artistic process. Beautifully complex and intricately woven in a way that not many films tend to be, Drive My Car is a gorgeous achievement, the kind that doesn’t come around often, but proves that there is always merit in measured cinema that touches on the deepest issues in a way that is profound and emotionally resonant, regardless of the subject matter.

If there was ever an artist that defied all logical rules or conventions, it would be Sparks. Somehow, over the course of their career (which spans over half a century), Ron and Russell Mael have continuously pushed the boundaries of their craft, transforming into one of the most influential musical acts of all time, albeit one that has rarely received the widespread acclaim they deserve. However, this all changed this past year with the release of two high-profile films that centre squarely on Sparks, and prove their unequivocal, uncontested genius. Annette (their long-gestating project developed alongside French iconoclast Leos Carax) and The Sparks Brothers (a documentary of epic scope, which serves as Edgar Wright’s love letter to a band he clearly adores) provide all the evidence one needs to fully comprehend them as artistic revolutionaries. It seems almost serendipitous that these two films were released in the same year – and as a result, they’re paired together here, since despite being perfectly wonderful when standing alone, placing them alongside each other seems natural. They enrich one another – considering a large portion of The Sparks Brothers focuses on their cinematic ambitions (and thus covers the development of Annette), one really could not exist without the other in a peculiar way. More than anything else, putting aside the musicians behind their creation, both films represent the best the year had to offer in terms of filmmaking – they’re incredibly well-composed works of distinct creativity that present some very clear artistic perspectives, and immerse the audience in the worlds created by these filmmakers. They’re incredible achievements all on their own, and while it may be a break from tradition to have two films sharing this top position, we can ask a very simple question: when have Sparks, Carax or Wright ever shown any interest in playing by the rules in the first place?

Condensing a year like 2021 into a single stream of film that represents the best is near impossible – but yet, this group encapsulates everything that made the past year special. Like any given year, there are a wide range of perspectives, drawn from many different backgrounds, that can be discussed – and these films manage to showcase exactly how strong the year was in terms of representation and diversity, both of which are evident in any cursory analysis of the wealth of films that we’ve seen over the last few months. This is only the start – 2021 was filled to the brim with excellent works (to the point where trying to create a list that thoroughly looks at the year was an enormous challenge, with many heartbreaking omissions throughout), and as more perspectives make their way into the mainstream, we’re likely going to see even stronger works not only produced, but recognized by the global audience, which is a truly encouraging thought when we consider how integral this art form is to capturing the world in all its unconventional and varied beauty. It is a good time to love cinema, isn’t it?