At the perfect intersection between screwball comedy and romantic melodrama resides People Will Talk, a daring and provocative film by the legendary Joseph L. Mankiewicz, who was operating at his creative peak around this time, having just redefined the Golden Age of Hollywood with the iconic All About Eve, as well as a range of other terrific films. This one in particular hasn’t received much attention in terms of being a classic era masterpiece, despite it having all the components that make for a thrilling film – tightly-written script, impeccable direction and very strong performances (including possibly the finest work ever done by an actor who probably embodies everything that made this era in cinema so unforgettable), all of which contribute to the deep and unflinching brilliance that underlies this film. It’s a work of profoundly moving romantic drama that conveys a deep message about individuality, with hints of social commentary that reflect the growing political and cultural divide that was ensconcing the United States in the post-war era, which is a concept that is seem perpetually through works produced at this time, when it almost seemed as if Hollywood was looking inward, paying attention to its own role in changing mindsets, often through the most subversive methods. Mankiewicz sits at the helm of this fascinating and insightful comedy that pays tribute to many deep and impactful issues, while still being as remarkably entertaining and engrossing as anything else he made in his long career – and if there was any proof how he was a director who could elevate even the most inconsequential of material, it’s found in this terrific and evocative blend of fascinating ideas.

It’s rather difficult to define People Will Talk along traditional genre lines – it defies any real categorization, being too intensely sobering to be entirely a comedy, while still have broad touches of humour that manifest in moments where they don’t only break the tension, but propel the plot forward in a very peculiar way. Mankiewicz had several tremendously interesting idiosyncrasies that persisted through his work, and they can all be found embedded deep in this film, which traverses a number of genres in its efforts to tell this enthralling story that is far too complex for a singular line of reasoning. There are numerous layers present in this film, so it only stands to reason that the specific approach to unravelling these many diverse themes that underpin this seemingly straightforward film. Constructed as a simple story of romance between two people thrown together not merely by chance, but rather by unavoidable (and perhaps even quite disconcerting) circumstances, the film takes its time to unpack many different ideas, gradually evolving into an oddly provocative story of defiance and rebellion against the status quo. An arousing and incendiary social satire hidden behind the glossy veneer of a major studio comedy, People Will Talk is quite a perplexing curio of a film, but one that constantly draws our attention to some more sobering themes in the form of moments of gentle humour and bewitching romance – after all, if a film is going to try its hand at changing perspectives, why would it choose to deliver its message in a form other than what was very clearly appealing to audiences, both at the time of production and from a contemporary perspective.

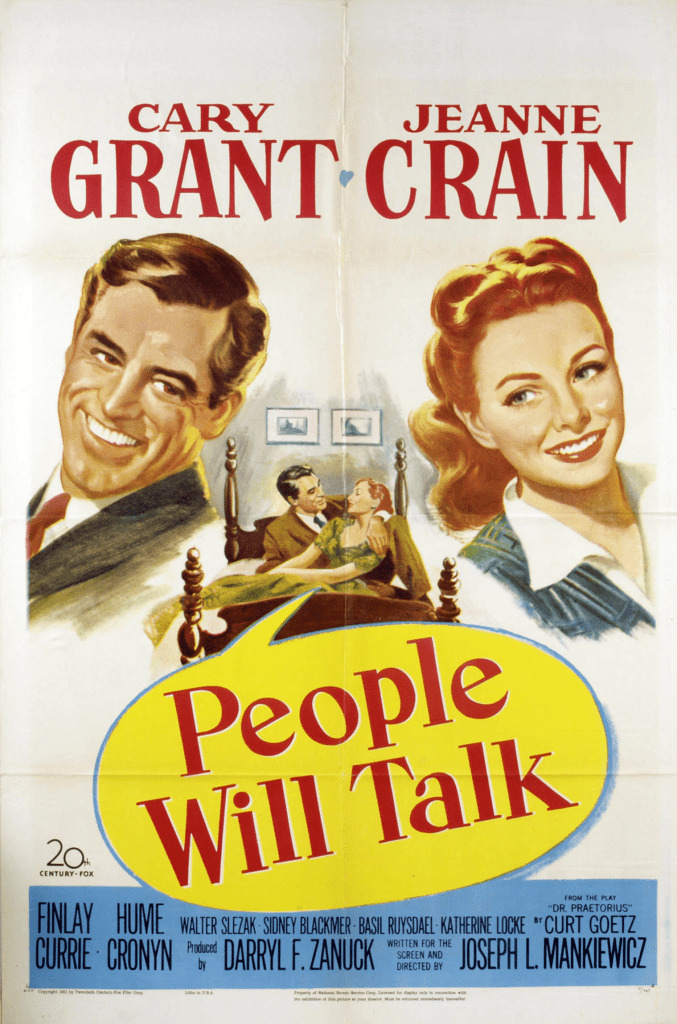

It’s impossible to look at an actor like Cary Grant and not be absolutely charmed. His debonair, suave personality, coupled with his very clear talents at playing introspective characters when it was required, made him arguably the best actor of his generation, someone who could carry an entire film entirely on his beloved charisma. The only problem with being so talented is that there isn’t a definitive work that stands as his very best performance – and while many will point to his work in earlier screwball comedies (specifically Bringing Up Baby and The Philadelphia Story), or his many collaborations with Alfred Hitchcock, I firmly believe that it’s his work in People Will Talk that stands as his finest hour. Never before had he had as much range as he did here – while he does play a character well within the confines of what he was comfortable with (a very intelligent, witty doctor who is always the most level-headed and logical man in any room), there’s something much more internal about his performance here. He’s not merely depending on his sophisticated magnetism, but rather attempting a much deeper, more intimate performance that sees the esteemed actor playing off his own reputation in a way that is vastly more self-reflective than anything else he had done at this point. Grant is the kind of actor who was never bad – he may have appeared in poor films on occasion, but his work ethic was always impeccable, so to see him turn in such a complex performance, while still staying true to the components that made him such an alluring and popular actor, is incredibly captivating. He’s so good, solid work from Jennie Crain and Hume Cronyn (the latter playing one of the most deliriously evil characters of this era in cinema), barely even register, considering the strength of Grant’s work.

Viewers may not know exactly what to expect when venturing into People Will Talk – after all, everything about it makes the film seem like a delightful romp through the burgeoning relationship forming between two individuals – yet it’s often quite serious in its perspective, never taking a single moment for granted, and ensuring every scene not only captivates the viewer, but pushes the plot forward. This is a film with an agenda, albeit one that only really starts to manifest towards the end, and even then, it requires some degree of attention on the part of the audience to figure out exactly what Mankiewicz was saying in these moments. Some have attributed the tense climax of the film, whereby the main character is finally wrangled into a conference room to undergo “a discussion”, which is just the bureaucratic shorthand for a trial where he is accused of posturing and harbouring a supposed fugitive (leading to one of the most breathtaking monologues in film history, given by Finlay Currie who proves how a single scene can define an entire performance), to the Red Scare, which was steadily approaching its peak around this time. There are clear political undertones throughout the film, but what makes the most impact are the social implications – the concept of an unwed mother goes against the puritanical nature of American society at the time, and there are even brief allusions to the main character living with another male companion not merely out of loyalty, but a mutual love for each other – this is not explored too much, and may even just be retrospective conjecture, but the nature of their relationship, whether platonic or otherwise, is a central theme to the film. There are numerous narrative threads woven together throughout People Will Talk, which proves how it is far more than just a conventional, run-of-the-mill comedy.

People Will Talk is the kind of film that doesn’t immediately proclaim itself as a masterpiece – this is a slow-burning film that doesn’t lay its intentions entirely bare at the outset, instead requiring us to bear with the story as we watch it unfold. It can be slightly slow at times, and even focus too much on the tedium that exists between the main characters – but it’s the cumulative power that really gives this film the sensation of being truly special, and Mankiewicz, who remains one of the most reliable directors of the Golden Age of Hollywood, knew exactly how to harness the most important material and turn it into a fascinating character study. The film combines genres and filters its very simple story through the guise of quite a traditional series of moments, until the third act, where it starts to spiral in another direction, bringing with it a rich and evocative sense of intricate detail that adds to the overall impact of the film. It may be unassuming, but People Will Talk is a tremendously entertaining film, especially considering how it manages to be enjoyable while still carrying an immense amount of weight in terms of subject matter, which gradually infiltrates the film in a way that is constructive and helps it move along at a steady, meaningful pace. By the end of the film, we’ve been accosted by some truly unforgettable storylines, introduced to a few wonderful characters and witness to a variety of misadventures that may seem inconsequential on the surface, but are vitally important in inciting conversations at a time when these issues were swept under the rug too frequently – and it’s all done in the form of a soaring romantic comedy that conceals many deeper truths about society.