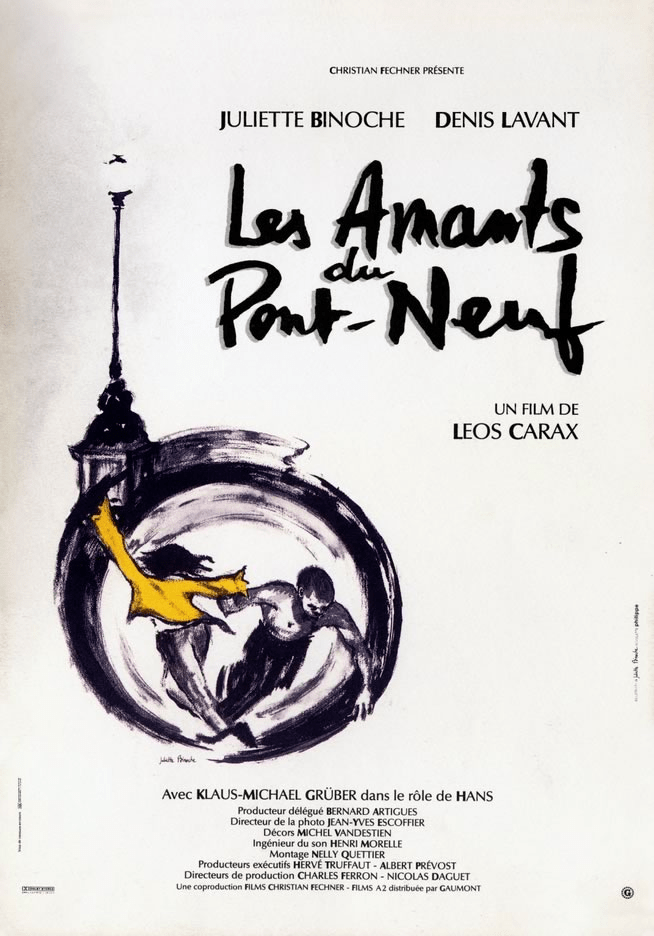

Once you spend a considerable amount of time with Leos Carax and his films, you start to realize that he is not a director all that interested in playing by the rules, preferring to entirely dismantle the art of filmmaking on both the narrative and visual level, while still retaining a sense of control and cohesion, which has made him one of the most exceptionally gifted auteurs of the past quarter of a century. Many of the director’s most significant qualities can be found in The Lovers on the Bridge (French: Les Amants du Pont-Neuf), his achingly moving manifesto on the nature of romance, and how true love can sprout from the most unexpected sources. The story of two vagrants that meet each other by chance on the eponymous bridge overlooking the River Seine in Paris is one that seems simple in theory, but is carefully explored by a director whose attention to detail and willingness to take many calculated risks for the sake of his craft have made him such an enigmatic figure. Beautifully made in terms of visual scope, and narratively quite cynical towards the surrounding world, but with a genuine sense of compassion that simmers beneath the surface when it comes to defining its characters, The Lovers on the Bridge presents us with a very unorthodox but doubtlessly fascinating series of moments that feel quite remarkable, especially for those who are either well-versed in Carax’s cinematic language, or those with an active interest in digging deeper into what is undeniably one of the most fascinating careers in contemporary French cinema.

The Lovers on the Bridge is the perfect collision of style and substance, which has been one of the primary reasons behind Carax’s ascent to the status of being one of the most incredibly innovative directors of his generation. However, despite his work being consistently rich and evocative, Carax remains an acquired taste, someone who is not as readily embraced by the general population, despite being incredibly inventive. You never quite know what to expect when setting foot into the director’s world, and this film does not offer much argument towards being an exception. From the first stunning moments of The Lovers on the Bridge, where we see the two titular characters walking down a quiet Parisian street by nightfall, separated by both physical distance and shared anonymity, we immediately can tell that this film is not going to be anything close to conventional, at least not in the sense of other similarly-themed films. His films may be challenging, but it’s important to consider that Carax doesn’t make films designed to play to the rafters – instead, he focuses on exploring his particular artistic interests, and anyone capable of grasping onto that wavelength will find themselves thrust into an unforgettable landscape viewed by the endlessly demented imagination of a true artist. It makes for supremely compelling viewing, with every frame of The Lovers on the Bridge exuding a kind of darkly unhinged beauty that only grows and develops into a riveting psychological drama that touches on a few incredibly complex themes with candour and extraordinary artistic resonance.

The Lovers on the Bridge feels handcrafted from various thematic fragments on the nature of one of the true universals – love. On the surface, this is not a film that is easy to categorize (which is par for the course with Carax’s films), as it embodies so many different themes and deconstructing a wide range of conventions, to the point where they become almost unrecognizable. However, the general narrative leads us towards looking at the film as Carax’s version of a romance, one that takes the form of a love story as filtered through the director’s disconcerting but hauntingly beautiful gaze. There are several compelling ideas woven into the fabric of the film, almost too many to fully encapsulate in such a short space – issues surrounding masculinity, the burden of the socio-economic conventions and the class system are all pivotal concepts that form the foundation of the film, rarely being directly addressed, but rather establishing a particular milieu from which Carax is working. He channels these ideas into the film by means of a directorial style that can only be described as being driven by a particular humanistic rhythm. The Lovers of the Bridge is fueled by a form of intense musicality, particularly in the movements of the characters through the space the film occupies, the fluidity of their motions reflecting how detached from reality the film is, while still being very much grounded within a recognizable version of our world. Setting the film primarily on a bridge (particularly one that is a national landmark), but with the caveat of this location, which was previously the epitome of idyllic, being under construction, is one of the many fascinating manifestations of the internal contradictions that would normally cause a more conventional film to falter, but which is here the basis for many of its most keen and compelling observations on the idea of space as not only a setting, but a character on its own.

Carax evokes a particular atmosphere in telling this story, with The Lovers on the Bridge essentially being a film driven by mood more than it is actual substantial structure. The film takes the form of a stream-of-consciousness narrative, which is brought to life by Denis Lavant (undeniably the director’s muse, and one of the few actors who have been fully attuned to Carax’s unconventional style, consistently turning in extraordinary performances through their regular collaborations), and Juliette Binoche, who was steadily ascending to the status of one of the most celebrated performers working in Europe at the time. Both Lavant and Binoche are reuniting with Carax after their work on Mauvais Sang, once again playing star-crossed lovers forced to find romance in hostile surroundings. Considering how unorthodox this film is, neither actor was able to turn in performances that can be considered particularly easy to dissect – Alex and Michèle are opaque, complex characters whose pasts are unknown and futures are ambigious. However, we simply can’t resist wanting to work our way deeper into their minds, which is not only credit to Carax who created these characters, but the actors themselves, who developed them alongside him, curating and experimenting with their physical and emotional inventories to create memorable protagonists, all under the careful guidance of the director, whose main responsibility in this regard was simply managing to capture all the exquisite detail Lavant and Binoche bring to their portrayals of these characters. It borders on performance art, especially in how Carax captures their movements through the city, Lavant’s physicality in particular becoming a major element of the narrative – there even comes a point where the dialogue begins to render as white noise, but because it is uninteresting, but due to the fact that we start to focus less on the words, and more the ambigious spaces between them – and it’s in those gaps that The Lovers on the Bridge has the most vivid and unforgettable impact.

The Lovers on the Bridge may not be a spectacle on the level of Holy Motors or Annette in terms of scope or style, but neither of those films could exist without this one, which allowed Carax the space and time to explore many of his more peculiar curiosities in a form that was experimental, but still accessible. It would be foolish to say that prospective viewers should be prepared before taking this voyage into the director’s world, because Carax has proven on every occasion that one can’t only expect the unexpected, but also needs to simply forego any logic in general, since it makes the journey all that more effective. The director’s vision is not one that necessarily adheres to the known laws of artistic theory, but rather shatters those conventions and rebuilds them through piecing together the more peculiar fragments, turning them into a stream of atypical concepts that may be bewildering at first, but gradually become incredibly enthralling the more we start to surrender to the central ideas, which begin to manifest the further we allow these ideas to develop organically. Watching a film like The Lovers on the Bridge is an active experience, where we occupy the role of voyeurs, quietly observing the routines of these characters, the director pushing us further into their lives, until we feel like we’re accompanying them on these metaphysical voyages of self-discovery. It culminates in a film that is rich and evocative, exuding a distinct and uncanny energy that is difficult to describe, and which has single-handedly established Carax as not only a great filmmaker, but a vital artist in every way.