The sheer amount of stories that we’ve seen written about capitalism, either its joys or failures, is almost too staggering to count, especially since they extend to the very outset of the idea of free-market economy, which some viewed as being indicative of a new level of outright freedom, others seeing it as a way for those with power to assert control over the masses, who fall victim to the belief that one can only achieve true satisfaction through exorbitant spending, a claim that has unfortunately become commonplace in the global culture. While this is a very deep discussion that requires a lot of nuance, we can see the impact of these ideas reflected in a number of artistic works, many of which tend to take a side on the debate and defend it with every ounce of their being. Rosalie Goes Shopping is a film that tackles this very issue, and while it is not well-known beyond a very niche group of supporters, Percy Adlon’s wickedly funny satire is one of the most scathing deconstructions of capitalism ever committed to film, the kind of vicious glimpse into contemporary matters that feels like it is genuinely in search of a deeper meaning, which it achieves through the most eccentric and well-composed storytelling imaginable – and all of it is kept extraordinarily intimate and understated, which contributes to the general message, as well as portraying this film as the kind of off-the-wall comedies that only come about sporadically, sinking into relative obscurity, patiently waiting to be discovered for viewers who will appreciate its bizarre energy, all of which is explored with precision and earnest conviction by a director who may not be particularly well-known, but has shown an aptitude for some peculiar but riveting ideas in his past work, of which Rosalie Goes Shopping may be his gem.

Somehow, this quaint little comedy set in rural Arkansas manages to be one of the most insightful conversations on the nature of capitalism ever produced, and whether it was accidental or intentional, Adlon created a memorable satire that feels like it was fueled by a clear frustration with the direction he saw the world heading, which clearly impelled him to write and direct a film that explored many relevant ideas, but without making it too heavy-handed, choosing to approach this issue from the perspective of a comedy, which we’ve seen can be the most effective tool for social commentary. Here, we’re shown the economic trials and tribulations of an ordinary family, who should be a comfortably working-class clan, had they not been led by a matriarch whose addiction to spending money is beyond reprieve, causing her to take up a hobby of swindling money from any institution she sees as foolish enough to part with their money, not realizing how she has so carefully and meticulously found a way to take advantage of their supposed generosity. It’s not a particularly high-concept film from a contemporary perspective (especially when we consider how the central conflict of Rosalie Goes Shopping occurs when she enters the online realm, which is so endearingly a product of its time, having dated in ways that are unintentionally hilarious), but taken as an attempt to focus on the supposed prosperous years of the 1980s, it tends to be sharper and funnier than more well-known satires – and the fact that Adlon (a German filmmaker) managed to provide such a pointed critique of American values and their unhealthy relationship with consumerism is impressive, being one of the areas in which this film is an unequivocal success, and worth more than it seems to be at a cursory glance.

To put it frankly, the premise to Rosalie Goes Shopping is very funny and has some strong ideas that stir conversations, but the narrative alone is not enough to sustain the film. As a result, Adlon was tasked with ensuring that the viewer would actually remember what we were seeing, which comes in the form of the tone, which is bizarre to say the least. Adlon approaches his films from a distinctly European point of view – the satire is pitch-black and often extremely subversive, and his method of portraying the decadence of this family is to present them as grotesque automatons of a post-capitalistic society – and managing to extract humour from this is an enormous achievement, and not one that is taken lightly. This is the reason behind Rosalie Goes Shopping not being particularly well-regarded, since it is far too polarizing to amass any kind of significant following, since it often borders on uncomfortable. Reviewers at the time noted that there was a dissonance between the narrative – which was designed to be an upbeat and endearing comedy – and the execution, which exudes a more significantly dark sense of humour, almost to the point where it can become repulsive. However, while this sounds like a flaw (and it was certainly meant as such when it was brought up in that way), it would be foolish to think this was not intentional – Adlon did have some experience, and while his works are not always particularly easy to decipher, they’re uniformly interesting, with the off-kilter tone and bizarre characterization contributing to his vaguely nightmarish vision of the direction in which he saw the modern world heading – and the fact that the film ends with the characters getting away without facing the consequences only proves how abstract the film aimed to be, which is a much stronger quality than it would seem.

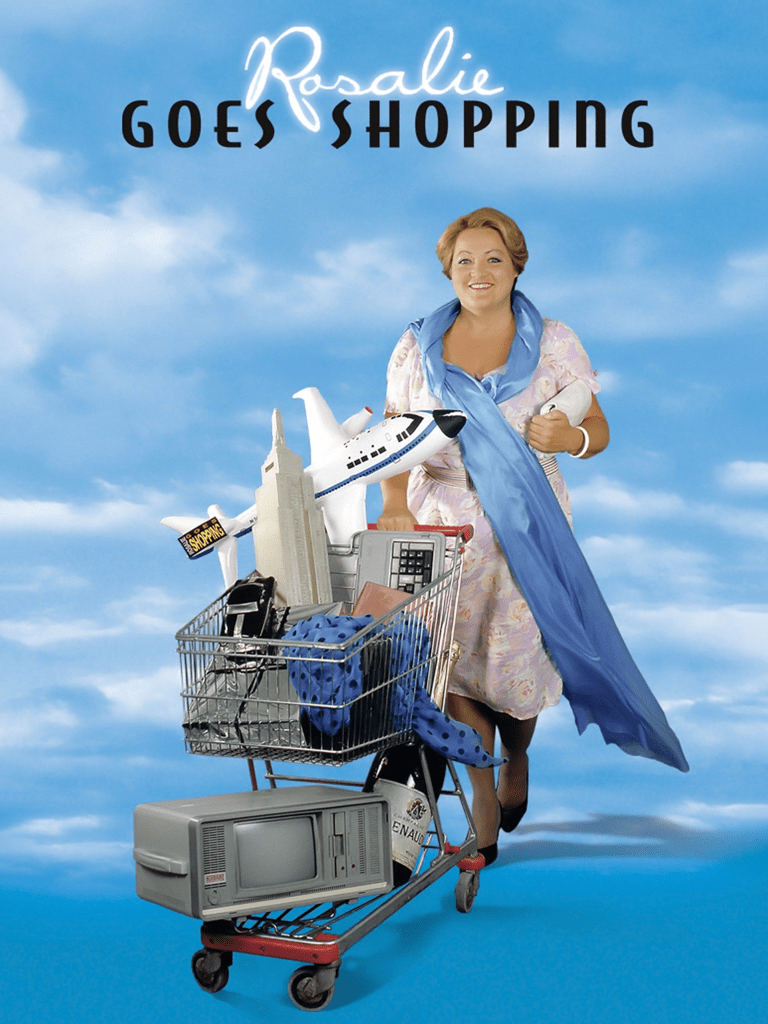

There are many reasons to appreciate Rosalie Goes Shopping, but the most significant of them has to be the performance given by Marianne Sägebrecht, who plays the titular character. In the hands of many other actresses, Rosalie would be beyond despicable – she is so addicted to spending money, she crosses the boundary of basic morality in order to fuel her desire to engage in a lavish lifestyle. She’s not written as a likeable character, but yet Sägebrecht plays her in such a way where we simply can’t help but be absolutely enamoured with her. Part of it is that she just emanates warmth, which betrays the very cold and arid nature of the film, which includes a range of other despicable characters – not a single person in this film outside of Rosalie is all that endearing, and they actually border on being quite despicable, despite ironically being the most moral of the characters, since they don’t engage in the criminal behaviour that Rosalie so casually finds pleasure in. Sägebrecht is such a unique actress, and her happy-go-lucky demeanour was a perfect complement to Adlon’s more deranged story. Special mention must go to Brad Davis, who is cast against type as the lovable but dim-witted husband of the main character who doesn’t realize the extent of his wife’s misdeeds, being blinded solely by his undying love for the woman he pledged to spend his entire life adoring. It takes a lot of work to cast such lovable actors in the roles of such morally reprehensible characters, but Adlon achieves it with flying colours.

It’s easy to just view Rosalie Goes Shopping as a minor film, nothing but a peculiar curio of a time when American cinema was having explicit discussions on issues that extended far further than most would have liked to admit. Sometimes, the most effective satires are those made by outsiders, and if it took a German director and a compatriot leading actress to make a film that provokes deep discussion on the nature of consumerism amongst the American working-class, then we can easily consider this film as something of a miracle, since the consistent blend of humour and pathos leads to a film that may be tonally uneven, but carries a deep and important message that ultimately means much more than anything else that is occurring in its close proximity. Rosalie Goes Shopping is not well-remembered outside of a few dedicated supporters, which is a shame, considering how not only is this film fascinating as a piece of satire, but it is wildly entertaining, having a deranged sense of humour that is unlike anything we are likely to see, and a genuine fondness for its subject matter, so much that we can excuse how strange the story can be at certain points. It deserves a re-evaluation, since there is genuine merit that exists beneath the surface of the film, which asks us firmly but politely to abandon all preconceived notions of reality, and just surrender to the madness – and there are few joys more potent than simply undergoing this strange journey with a film that is fully aware of its absurdity.