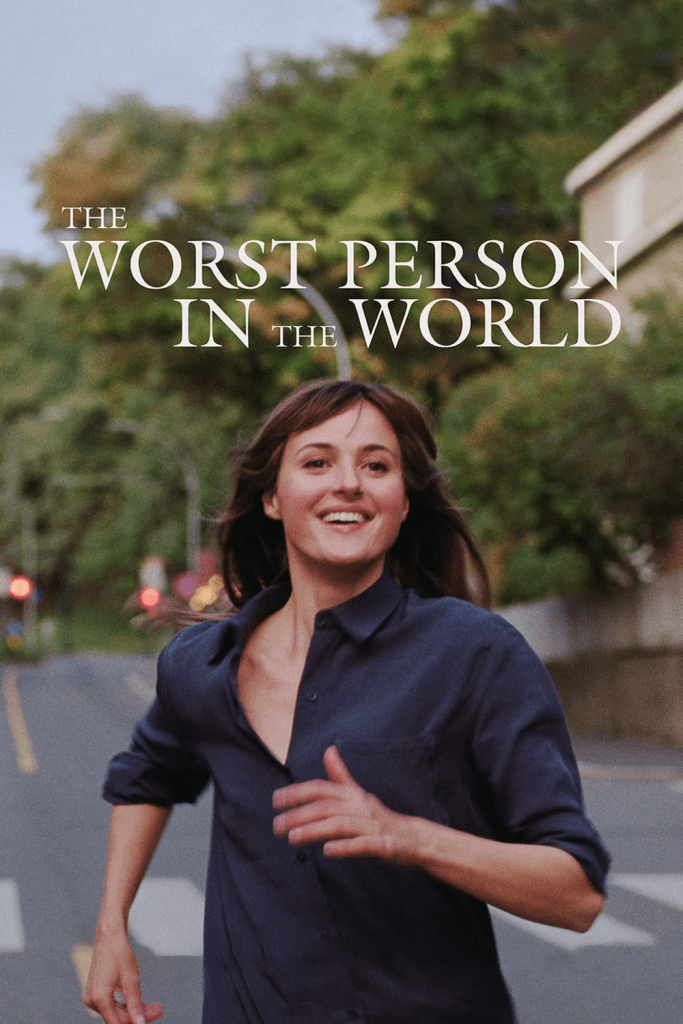

There comes a point in everyone’s lives where we just wish to freeze time, and run through the streets, liberated from the need to partake in a world that grows increasingly more hostile the more we uncover its secrets, which is one of the inevitabilities of venturing into adulthood. This concept is the centrepiece scene of The Worst Person in the World (Norwegian: Verdens verste menneske), the ambitious dark comedy by Joachim Trier, who completes his trilogy of young people in contemporary Oslo. The film, like its predecessors, follows the trials and tribulations of a complex protagonist as she works her way through a city she is starting to find unrecognizable, the faces she encounters becoming more difficult to embrace as she begins to realize that life is not as easy as it was supposed to be, and that one’s audacious plans for the future may not always come to fruition – in fact, for many they don’t even come close. Beautifully deranged but heartbreaking in a way that only the most well-formed dramas tend to be, Trier’s work in The Worst Person in the World is truly superlative, the direct nature of the story allowing the director, who has also demonstrated incredible candour, even in some films that may not be as successful in execution as they were in theory, to comment on broad issues, filtering them through the perspective of a group of characters who are both archetypes and truly original creations (one of the many contradictions present in the film), who form the foundation for a story that will resonate with all young people, particularly those who have ever felt lost in life they never asked to be a part of – but like we see reflected in the main character as she gleefully gallops through those idyllic Scandinavian streets, there is value in simply letting go and surrendering to the fact that life is thoroughly unpredictable.

Trier clearly had many intentions when it came to putting together The Worst Person in the World, the primary of them being his aim to compose a vivid portrait of contemporary Oslo, and the people that inhabit it. In many ways, the film is as much about the city as it is about the people who we meet along the way, the director having made a few films set in the city in which most of his childhood took place, each one of them being a well-constructed glimpse into the various Oslovian mentalities, particularly amongst different generations, which has been a concept that Trier has explored quite thoroughly throughout his films. The Worst Person in the World takes us on a journey into the lives of one character in particular as she makes her way through the city at different stages – we see her traverse universities, suburban areas and more urban locations, each one of them telling a different story. There are brief sojourns into the countryside that starkly contrast the bustling metropolis in which Julie finds herself for most of the film. This is far from an attempt to drum up interest in tourism opportunities for the city, but instead a way for Trier to explore different components of this city, which he views as a living, breathing entity that depends on each individual to give it nuance, since a town can only be as interesting as the people that live there. Considering how much of The Worst Person in the World seems to depend on the characters (as reflected in the title itself), it’s a bizarre concept to think that the film is actually one more invested in looking at a wider population, rather than just one character – but it is her perspective that facilitates these fascinating discussions, the dialogue between Julie and her surroundings, whether she is questioning her identity on her own, or working through a range of existential dilemmas across from someone, leading to some insightful and bitterly caustic commentary that sets a firm foundation for one of the best satires of recent years.

Trier has always been devout in his investment to exploring the human condition, and such interests simply could not be possible without interesting characters. Mercifully, despite the title of the film, The Worst Person in the World is centred on someone who is actually quite likeable, with the character of Julie being brought to life by the gifted Renate Reinsve, whose spirited performance as this flighty young woman who is wholly unsure of her future is one of the year’s most compelling. She grounds the film with a kind of quiet charisma that is never too overly boisterous – when given the chance to go broad, Reinsve chooses to reign it in and keep the character as realistic as possible, adding to the genuine sense of candour that dominates the film. The film is told in twelve distinct chapters, nearly all of them focusing on various moments in the life of Julie as she goes about her everyday routine, which we soon discover is essentially just meandering through the world, trying various existential disguises on for disguise, in the hopes that she will be able to fool someone for just long enough to convince them that this is her true self. Julie is an intentionally opaque character – much like her friends and family, the audience never knows where we stand with her, and Trier is not against presenting his protagonist as an inherently flawed young woman, since everything that she represents comes across as being very relevant to the story, which in turns carries a very simple message: absolutely none of us know exactly what the future holds, some just manage to hide it better than others. Julie is at an awkward age, caught between the reckless days of her twenties, and the more responsible stage of her thirties, the transition being a pivotal moment in the film, and one of the themes Trier is most interested in exploring. We may not form the strongest relationship with Julie, but we genuinely start to care about her through Reinsve’s spirited and layered performance, which harbours an abundance of meaning, even when the character is far more vague than we’d expect.

One of the most fascinating discoveries that comes with watching The Worst Person in the World is that, while the film may be focused on Julie, the character who truly wins our hearts is that of Aksel, played by the incomparable Anders Danielsen Lie, who is turning in quite possibly the best performance of the year, playing this tenacious young man who is in just as much of a philosophical model as the woman with whom he begins a tumultuous relationship. Quiet, brooding and interesting, his portrayal of the dedicated graphic novelist who starts to question his own authenticity as an artist (and by extent, his entire existence) being one that anchors the film. He may not be the focus, but yet much like Julie, our minds are continuously drifting back to him. Trier clearly constructed Aksel as someone of a surrogate for his own artistic quandaries, writing him as a young man on the precipice of a mid-life crisis, wondering how he works his way out of this situation. There is a whole other film that could’ve been made that follows Aksel as he works through his own issues, whether it be his artistic curiosities (especially since one of the film’s most enduring storylines is the transformation of his acclaimed underground cartoon from an X-rated satire to a children’s film), or matters to do with his own mortality. There is very little opportunity to deny that what Danielsen Lie is doing is incredible, his character serving as the emotional heart of the film, the propellant behind many of the main character’s decisions, and the ultimate reason for her eventual ability to look into the future, not with fear or concern, but with a smile, since having known someone who managed to endure what Aksel did throughout his life is very likely going to inspire anyone. So much of the film benefits from the incredible chemistry between the two characters, whose relationship could’ve sustained the entire film – but it’s their drifting apart that makes The Worst Person in the World such a complex but beautiful story.

The Worst Person in the World is a difficult film to encapsulate under specific categories, since it is so inherently different from what we would normally expect from such a story, while remaining relatively traditional. This is not a difficult film, and is actually quite entertaining, constantly carrying a very effervescent quality, even in the more tragic moments. The marketing has seemed to draw on the more passionate aspects of the story and the characters that it represents, creating the illusion that The Worst Person in the World is a romantic comedy – but herein lies the inherent problem, since Trier has certainly made a comedy, and there is an abundance of romance in it. Yet, it never feels like any of the more traditional romantic comedies we normally encounter, mainly because this is not a film about love, at least not the kind we’d expect. The director has made a film about a woman falling in love, but rather than being with another person, she is starting to relish in her own individuality, starting to adore herself in the same way that she hoped to be loved by a partner. There’s a valuable piece of wisdom contained in this film: if someone is waiting for another person to make them feel whole, they will never feel whole. Love comes from within, and that is exactly where the most significant merits of The Worst Person in the World begin to manifest. Julie may have a series of relationships, two of them in particular being more meaningful than others – yet, she doesn’t seem to fall in love until the very end, which also happens to be the moment she realizes the person that meant the most to her can no longer be in her life, leading to the realization that the fiery passion she felt wasn’t meant to be used on a loveless relationship with another person, but rather developing herself into a strong, independent woman – and somehow, Trier manages to do this with seemingly very little difficulty, exploring the long and arduous journey undertaken by a relatively ordinary young woman as she starts to see how much value there is in just surrendering to the fact that true love comes from within, not from the validation that emerges in a seemingly serious relationship.

Despite being a comedy (and it certainly qualifies as such – there are moments of genuinely outrageous humour contained in this otherwise deep and philosophical film), The Worst Person in the World approaches its narrative with a kind of sobering stoicism that works in tandem with the comedic elements to create a vivid and varied existential landscape. Driven by dialogue, everything that Trier is doing with this film is motivated by his continuous search for deeper meaning. There’s a genuine sense of emotional catharsis that comes with following the main character, who is not remarkable in any discernible way, navigating her surroundings, never being entirely sure of where this path is leading her, but still doubtlessly travelling down these paths, not knowing whether they’re fruitful or treacherous. Anyone who has ever been young and aimless will be able to relate to the emotional heart of the film, especially in how the director asks some forthright, direct questions. Trier rarely holds back on any of the important issues, actively inciting conversation that would otherwise be considered inappropriate in the hands of someone who didn’t know how to handle the emotional nuances. Much of this can be found in the relationship between Julie and Aksel, who (despite their difference in age and radical variance in mentality and temperament) manage to find a kind of rare symbiosis, filling in the void that both were missing. The film refuses to be cliched, but it does follow conventions to a certain degree, taking an active role in redefining what modern romance actually entails – and the blend of comedy and drama creates an atmosphere that can be both playful and heartbreaking, often at the exact same time, and undergoing the experiment of seeing if he can break our heart while still making us laugh, Trier triumphs wholeheartedly.

There’s such a genuine quality to The Worst Person in the World, a kind of honesty that isn’t often found in mainstream cinema. This film is profoundly Scandinavian in its sensibilities – the dialogue-driven narratives that draw attention to the deeper components of the human condition hearkening back to an era of very insightful, beautifully humane dramas that could see two individuals sitting across from each other, and yet still be as riveting and enthralling in its emotions than any other film. Trier has achieved something so special with The Worst Person in the World, working through some very tricky narrative territory to explore themes that are far more profoundly moving than we’d think at first glance. He continues to revolutionize cinema under his own endlessly ambitious vision, and whether through provoking deeper ideas on romance, or questioning the very fabric of humanity, Trier is constantly on the prowl for new stories to tell, and may have made his masterpiece with The Worst Person in the World, which carries a depth and nuance that most films would never be able to even fathom, let alone produce with such sincerity. It’s a masterful and often quite frighteningly realistic portrait of the younger generation, the people who have been thrust into an uncertain world, one driven by new obstacles, and forced to adapt or fear being left behind. It all converges in this absolutely mesmerizing philosophical comedy that has very few qualms in actively going against the status quo, questioning deeper issues while riling the audience into uproarious laughter, a careful creative choice that places the film in direct contrast with a range of deeper conversations centred on human issues that transcend geographical and temporal space, instead working their way directly into the heart of every viewer who chooses to accompany the main character on this metaphysical journey of self-realization and human curiosity.