We can divide the career of Pier Paolo Pasolini into various eras, based on both the specific stories he was focusing on, and the motivations behind telling them. His adaptations were the most interesting, and regardless of whether the director was making something faithful to the source material, or transposing these themes onto a more modern or local context, they were always worth watching. His era of adapting Greek myths into gorgeous existential epics are truly captivating, as evident by Medea, which he bases around the play by Euripides, which looked at the myth of Jason and the Argonauts from the perspective of a beguiling woman who possesses a kind of power that not even she knows how to fully utilize. There are many reasons to appreciate what Pasolini was doing with this film, and even at its most meandering, it proves to consistently be a beautifully constructed historical epic with broad overtures of surrealism, which the director has often utilized as one of his most unique and celebrated qualities, and which was put to excellent use here. Every one of Pasolini’s films reminds of us of what a considerable talent he was – from the excellent filmmaking methods, to the most intricate details in terms of both visual scope and narrative prowess, he was a director with a clear vision, and whose audacity was not matched by the time in which he was born, meaning that he would often be the subject of ire for even the most inconsequential of productions – and while it is not outwardly provocative, there’s a sense of rebellion in even a film like Medea, which means that it was not initially understood at the time, but instead has grown to be embraced by more modern audiences instead.

While it may not be the most well-known of Pasolini’s forays into the antiquity, Medea is still an incredibly fascinating film for a number of reasons. Primarily, it is not aiming to be the definitive version of this myth, while still remaining incredibly close to the source material, so much that it is almost undeniably amongst the most faithful accounts of the Medea story, with the director utilizing both the original text by Euripides (which itself has been the basis for countless other works, whether serving as the foundation for direct adaptations, or merely being a loose inspiration for narratives that use the general tenets of the story), or drawing on the extensive body of writing that is available by scholars of Greek mythology, who have tackled this fascinating story in a range of ways over the years. Regardless of the specific approach that we take in understanding the work, Pasolini’s version is one that clearly respects the original text, but is not against creatively adapting it in a way that fits his directorial vision. Never one to necessarily reject the idea of modernizing a text, Medea represents the director as his most subversive, focusing on his efforts to leap back into the antiquity and relay a well-known story in a way that is vibrant and exciting, and most importantly, honours the legacy of the source, which is really the impetus for this film, rather than being an attempt to draw correlations between the modern world and those days of yore, which is often a launching-point for the majority of similarly-themed films.

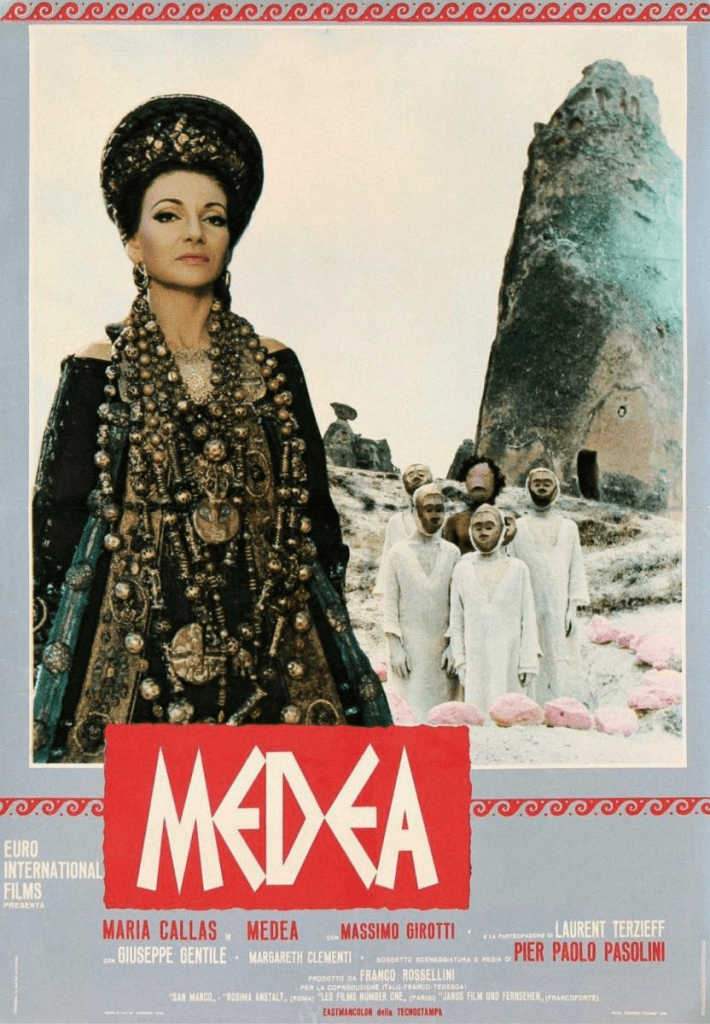

Perhaps the primary attraction of this version of Medea is the person who occupies the titular role. Maria Callas is a folkloric figure, someone whose incredible voice and unfortunately short life has made her an enigmatic individual whose legacy has remained as peculiar as her life, shrouded in mystique and curiosity. It seems almost serendipitous for Pasolini to cast someone of such considerable global status in a film that centres on mythology, since Callas herself was something of a celestial entity in her own right. This film represents the first and only time she had ever acted in a film, and while she was a natural-born performer that could command the stage, regardless of whether she was playing herself or a character, there was clearly a bigger challenge in forcing her to leave behind her voice (undeniably her most powerful tool), and instead focusing on her presence. Mercifully, the camera adores Callas – the way Pasolini captures her is incredible, his clear reverence for this artist being clear in absolutely every frame, and she rises to the occasion, playing the titular role with such extraordinary intensity, it’s bewildering that this was technically her screen debut. It certainly does help that Pasolini approached Medea in much the same way a director would construct a play, just setting it on a much wider stage, and focusing more on the intimate details. To say that Callas was a revelation implies that her talents were underestimated at first, and while this is far from the truth, it’s fascinating to note how his dynamic and magnetic performance was the sole instance of Callas acting on screen. It may be the main reason behind the lasting legacy of Medea, but it’s certainly not an undeserved one.

While we may be drawn into this film for Callas’ performance, what really keeps us invested in the actual filmmaking, which is directly attributed to Pasolini and his unique approach to visualising his stories. The director was intent on making an epic set in Ancient Greece (and the worlds that surrounded it), and naturally, very little expense is wasted in ensuring that Medea looks the part. Filmed in several locations, ranging from Syria to Italy, the film is absolutely gorgeous. Director of photography Ennio Guarnieri works closely with Pasolini to create a spellbinding version of what they imagine the ancient world would have entailed, filming most of this story in real locations, whether those preserved from the antiquity, or those built specifically to honour it, including churches and temples, which add a level of authenticity to a film that didn’t necessarily require it (since Pasolini’s vision is strong enough to have made this entire film on a soundstage without a single piece of scenery), which only makes the film so much richer and evocative. This isn’t the kind of epic that lends itself to excess in the way that many that came before it did – instead, it takes a very minimal approach, using sparse resources and depending on the splendour of the natural world to evoke the spirit of the past, which makes for a thrilling and truly evocative piece of storytelling that is as rich as it is thought-provoking.

Pasolini constantly demonstrated a keen ability to make films that were both sprawling and intimate, and this can be seen in every frame of Medea. He didn’t have a particularly easy task in taking on this subject, since this myth is one of the most well-regarded, and has been subjected to several interpretations over the centuries. This version is close enough to be reliable and faithful, but deviates in smaller but creative ways, which leads to a much more vivid, interesting narrative that feels genuinely interesting and dynamic, rather than simply rehashing the same aspects of the story we can find in any cursory retelling of this myth. Whether it be in the visual landscape that serves as the home for this story, or the narrative detail that went into the creation of the film, Medea is an absolute triumph, a film that may not rise to the heights of other Pasolini films, but at least carries with it a sense of earnest intelligence and a willingness to experiment with form and content, without aiming to be all that revolutionary. Beautifully made, bewildering in a way that piques our curiosity, and incredibly complex, this film is a triumphant example of historical and mythological filmmaking colliding to form a stunning and unforgettable series of moments, all of which service a directorial vision that is beyond brilliant, as evident by his continuous efforts to redefine the boundaries of cinema through his own unique artistic curiosities.