Jean Renoir is one of a few artists who can easily lay claim to being one of the finest filmmakers of any generation – his work stretched across the decades, and saw the director tackle every conceivable side of society through his elegant, fascinating works. One of his most interesting qualities was his ability to move outside of the genres and settings he knew, and instead occasionally embrace entirely new environments and conventions, while still staying very true to his distinctive style of filmmaking. The River is one of his most cherished works, earning its reputation for a variety of reasons, whether it be the director’s very sincere portrayal of Indian culture, the captivating performances he extracts from his actors, or simply his genuine interest in the subject matter, which is reflected in every gorgeous frame of this film. In no uncertain terms, Renoir struck a raw nerve with The River, weaving together a number of complex themes in his pursuit of a few deeper truths, all of which manifest throughout this beautifully poetic, and often quite lighthearted, drama about the ability for common ground to be found between the most unexpected characters, who many would not expect to work together as well as the people at the heart of this film did – but through compassionate and genuinely insightful commentary, Renoir achieves exactly what he aimed to, and produced a staggering drama about the human condition that says more about life than many other films produced around this time.

More than a filmmaker, Renoir was a social critic – his films often reflecting different aspects of the cultural approach to society, and how there is a clear delineation between classes in nearly every country and their traditions. Considering much of his work focused on the varying strata that exist in cultures, it makes sense that the director would be interested in making a film centred on postcolonial India, a country that had only just been given independence, thus making it fertile ground for a multilayered exploration of the nation and its various customs. The River is a film about cultures coming into contact, and either merging together in ways that bolster both perspectives, or clashing to the point where it becomes almost hostile, both principles serving as the foundations for this film. From the first moment, the narrator begins to describe the differences that we’d encounter throughout the film, with the assumption being that the target audience for the film will be those from a western perspective. Considering India had previously been considered the “dark subcontinent”, any film that strove to pull it out of these trite stereotypes and explore the beautiful cultural nuances is going to earn a great deal of respectability, especially when the story at its core is less about exploiting the natives and promoting the agenda of the supposedly “civilised” westerners, but rather finding similarities between the two and proving that harmony is more than possible, especially in the shadow of the postcolonial project. The lack of condescending remarks, and the promotion of meaningful and realistic depictions of the country serve as the fundamental basis for the success of this film.

The River is not the definitive text on postcolonial relations between different groups, but it does have a degree of merit in how it is one of the first western-produced projects that aims to shed light on the lives of the Indian people as much as it did those who were involved in the colonial project, even indirectly. Renoir approaches this difficult subject with a very simple but oddly rare quality: undying respect. Not once in The River do we feel as if the director is exploiting these people, or succumbing to the outdated idea of the exotic east. India isn’t portrayed as some mystical land of strange customs and traditions, but rather a growing country that is thriving through its newfound independence. One has to credit a very young Satyajit Ray for some of this perspective, as he worked as both an advisor to Renoir, and as one of his assistant directors, the intelligent and gifted future filmmaker offering unique insights into the intricate traditions of his beloved country – and which he’d soon develop into his own filmmaking career that would gradually become one of the most important in the history of the medium. The exoticism of the Indian subcontinent is not entirely missing, since this is still a film about cultural differences, as filtered through the eyes of a white colonial family – but instead of placing the natives in the background without any depth, the film positions them as major characters in their own right, their cultural idiosyncrasies being the foundation on which the film is built, leading to a truly respectful and honest depiction of the multitudes of Indian traditions, at least as much as we could feasibly expect from a director who mainly worked in western cinema.

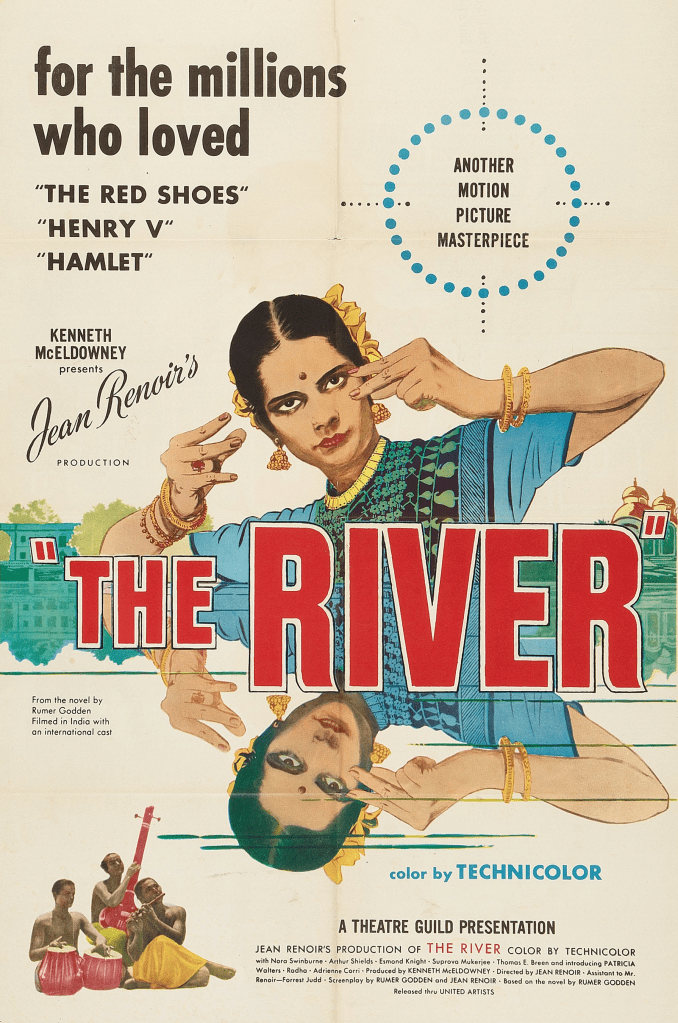

Somehow, The River is an anomaly, since it feels both intimate and epic, often simultaneously. We can easily credit this to Renoir, whose work almost uniformly consists of multilayered representations of society, since he often focuses on both the culture in general (providing a deep analysis of a particular group), and a very specific set of individuals that populate it. In this regard, the film offers a deep glimpse into the lives of those who live around the Ganges River in India, which is more than just a body of water, but a sacred entity that is truly revered by those native to the country and its religious foundations. Renoir breaks from the traditions of his peers and actually shoots on location (which is allegedly where his professional relationship with Ray started, with the young artist aiding in scouting locations and introducing the director to the country and its customs), which allows the film to be as visually stunning as it is narratively rich. Filmed in gorgeous Technicolour that showcases the smallest details of the stunning locations, The River truly captures the spirit of India with deep reverence. Interestingly, the scenes that take place on constructed sets, while still quite beautiful, pale in comparison to the raw representation of India, which is captured with such striking simplicity, the most meaningful shots being those that showcase the country in its most natural, untouched state – and Renoir’s dedication to allowing this beautiful nation to tell its own story through its locations and people is one of the primary reasons that The River is such a triumph. This is a film about love – not only in terms of the central premise of a young woman feeling the first sensations of romance, but also a broader demonstration of a great artist’s absolutely adoration for this country and its cultures.

It may not be the most entirely authentic version of India, since ultimately regardless of the level of respect, it was still made primarily by western filmmakers who asserted their own ideals on the country. However, The River is still a worthwhile venture, since it feels genuinely insightful and compassionate, being made with the kind of stark precision we have come to expect from Renoir, even when he was working outside of his supposed comfort zone. There isn’t too much to the film in terms of overarching ideas – outside of being a vivid portrait of postcolonial India, it is really just a coming-of-age story combined with an intricate process of comparing and contrasting two wildly different cultures that serve as the foundation for this film. It’s not necessarily the peak of Renoir’s talents, but it does feature many of his most cherished characteristics – good-natured humour, sweeping social critiques and a genuine interest in exploring the lives of a wide range of people. It’s a warm and enticing film that keeps everything very close to its heart, and allows us to look behind the cultural curtain, privy to the intricate details of traditions that may appear foreign to those of us who have never experienced Indian culture firsthand, with The River being a passable effort to give viewers a glimpse into the country’s history. If nothing else, this film may have indirectly facilitated the career of someone who certainly did work for nearly half a century on capturing his homeland’s culture in beautiful detail, so even if we dismiss the perspective Renoir offers, we can at least appreciate the fact that this may have helped us gain the incredible career of Ray, whose involvement here is not only a fascinating bit of trivia, but a worthy footnote to an otherwise captivating and thrilling romantic and cultural drama.