As they say, there’s no business like showbusiness – and no one will remind you of this fact faster than those working within the entertainment industry, whether for better or worse. Hollywood has had a preoccupation with telling stories about itself on numerous occasions, almost from the time it came into being – and over the years, we’ve seen many fascinating works produced on the subject of young people trying to make a name for themselves in the notoriously challenging and hostile world of the motion picture industry. Inside Daisy Clover is Robert Mulligan’s contribution to the discussion, working with longtime producer Alan J. Pakula in this adaptation of the novel by Gavin Lambert, which tells the story of the titular young starlet who decides to pursue her dream of making it big in the movies, only to realize that it is a much more cutthroat world than she imagined. There are many dark corners lurking on the other side of the silver screen, and as she learns through several years of immersing herself in this world, there is often very little possibility of escaping, at least not in a form that will allow her to retain the more endearing elements of being a world-famous actress. Inside Daisy Clover, while inarguably not anything particularly revolutionary (especially considering how it is essentially just a lighter version of A Star Is Born, had it been solely from the female lead’s perspective), is a fascinating work that may not always achieve everything it aims to do, but still manages to be an insightful and meaningful glimpse into the more haunting side of Hollywood, an industry that builds as many dreams as it does broken hearts, a pointed but compelling critique with its roots in a very recognizable reality.

Films that take a self-referential stance are essentially a dime-a-dozen by now, having their roots in the earliest days of filmmaking – whether scathing satire or heartwrenching melodrama, there wasn’t any shortage of works that reflected on the brutal realities faced by those in Hollywood. Inside Daisy Clover certainly doesn’t do anything we haven’t seen before – it follows the same identical plot patterns, starting with a rambunctious young teenager who dreams of international stardom, which she eventually receives, but at an enormous expense, whether it be the loss of her identity, the heartbreaking distancing from her friends and family (who she willingly sacrifices in favour of pursuing fame), or the unreasonable expectations layered upon her, which very few self-respecting individuals would agree to honour. The Faustian nature of ascending to worldwide fame, losing one’s soul in favour of recognition from wider audiences, is a pivotal aspect of these films, and neither Lambert in the original novel, nor Mulligan in his adaptation, seem to be all that interested in abandoning this cliched but reliable trope. Hollywood loves the sound of its own voice, so even when actively deconstructing perceptions and proving that it is far from the ideal artistic utopia many ignorant young people seem to believe, it is fully committed to telling such a story. Inside Daisy Clover isn’t the fervent celebration of the uniting power of cinema that we saw in the 1940s – instead, its a brutal and heartwrenching melodrama with slight smatterings of humour to break the tension, all centred around the transformation of the main character from youthful ingenue to mainstream star, describing in detail the harrowing personal and psychological challenges she faced along the way.

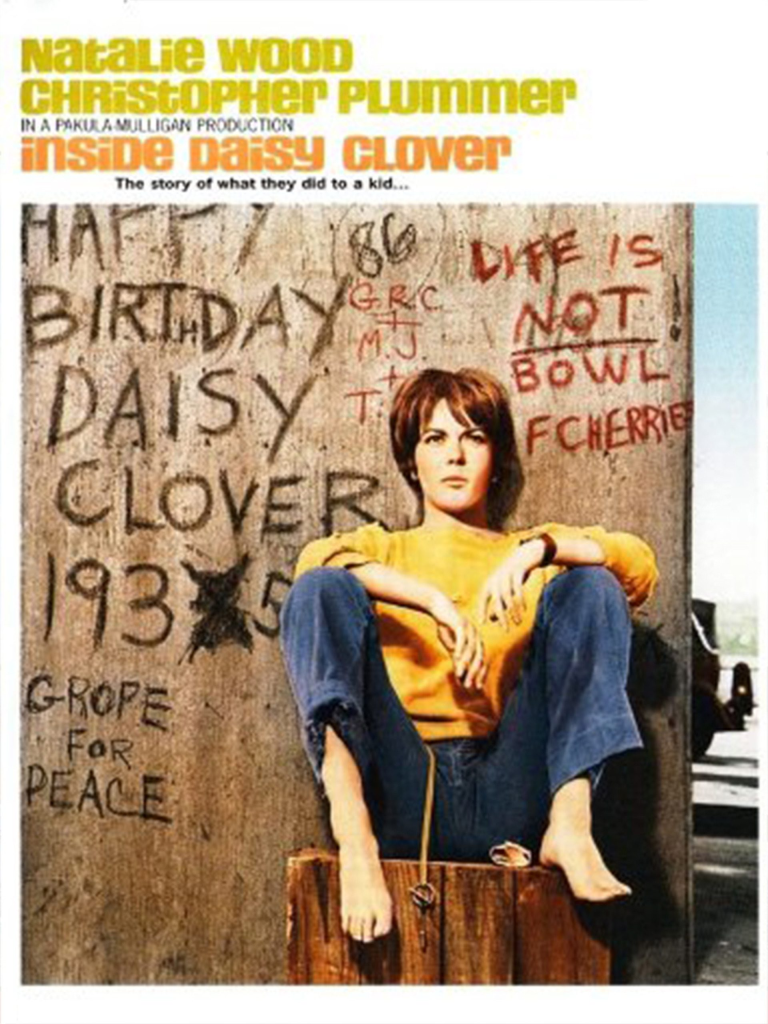

Logically, Inside Daisy Clover depends almost entirely on its actors, since there is nothing about the story itself (or Mulligan’s effective but pedestrian directing) that suggests it is anything remarkable. The performances are exceptionally strong, even when they do get off to a slightly uneven start. Natalie Wood is the titular young actress, and plays the role of Daisy with such conviction, it is easy to overlook the clear problems with her casting. While she is excellent and turns in a great performance, there is something off-kilter with her presence – like Kim Stanley in the similarly-themed The Goddess from a few years prior, Wood almost possesses too much depth and gravitas, meaning that she never fully becomes the innocent, naive young Daisy – she carries herself with a genuine maturity that makes suspending disbelief almost impossible. However, it’s less a problem with her performance, and more the character she is playing, which doesn’t seem tailor-made to fit the actress’ unique gifts. Christopher Plummer is delightfully evil as the proverbial “Prince of Darkness” that kickstarts Daisy’s career, and as a result has complete control of it (even more impressive considering this was the same year as his valiant performance in Robert Wise’s The Sound of Music), while Robert Redford, in one of his first starring roles, demonstrates the unique blend of charisma and depth that we’d personify in the coming decades with stark regularity. The presence of Ruth Gordon (returning to screen acting for the first time in over two decades), as Daisy’s loving but delusional mother, only confirms that this ensemble is filled with gifted performers, the veteran writer-actress turning in a performance that not only reminded audiences of her gifts, and reignited a wonderful second-act in her already iconic career. Inside Daisy Clover is quite rightly defined by its actors, who elevate the material and add complexity to what is essentially a very straightforward narrative.

The ideal version of Inside Daisy Clover is a film that gives us genuine insights into the main character’s journey, and all the challenges she faces along the way to stardom. Unfortunately, this dramatic peak happens very early on, where she is suddenly a star within only a few minutes of the film beginning – the actual events that led her to being noticed by Plummer’s character are not seen, but rather briefly mentioned (and even then, in a way that is quite flimsy and not always logical), and within twenty minutes, she’s already a major star – and for a film that runs over two hours, this means that there is a lot of space between her ascent to fame, and her eventual decline. This isn’t to imply this is a bad film at all – it just feels as if it could’ve been either trimmed, with the exposition-heavy second-act being radically excised, or at least shortened to the point where there weren’t so many plot threads that didn’t have much of a resolution (nor necessarily needed them, as they didn’t contribute to the story in any significant way). At its core, Inside Daisy Clover has many incredible ideas – the most common citation this film receives is that it is one of the first instances of a mainstream film that featured a queer character in the context that he wasn’t self-loathing or remorseful for his “deviant” identity, and the film does well in making sure that Redford’s character isn’t the subject of unnecessary scorn outside of the logical discussion on infidelity. One of the film’s greatest strengths is how it doesn’t descend too deep into melodrama – everything is kept extremely simple and straightforward, the emotions genuine enough to justify some of the more unconventional scenarios the characters find themselves engaging in throughout the story.

Inside Daisy Clover is not particularly revolutionary, but mercifully it doesn’t need to be. It understands the constraints of such a story, and never really trie s to go beyond what we would expect. It is anchored by a great cast, who do impeccable work in interpreting these characters, who essentially define the story and keep the plot moving, especially since the films often ignores the potentially interesting areas in which this premise could’ve been taken in favour of adhering quite strictly to what is essentially nothing more than a very traditional “rags to riches” story of fame, with added layers of socio-cultural commentary thrown in to indicate that this is a film made under the guidelines of the burgeoning New Hollywood movement, where such edgy and controversial subjects could easily be found, rather than the more measured and carefully-constructed Golden Age, which such topics would be found under layers of implication. As a whole, Inside Daisy Clover is a well-made, solid drama with some impressive moments (every musical performance is absolutely dazzling, and proves what an immensely talented, multifaceted performer Wood was), and a lot of heartful discussion on some very deep issues. It may not go too in-depth on many of them, but continuously presses forward to become an absolutely spellbinding, meaningful showbusiness satire with a good sense of humour and an abundance of earnest authenticity, enough to qualify this as a film much better than its reputation may imply.