When it comes to looking at a film about important issues, we have to make a difficult decision in our adjudication – can subpar writing be redeemed through good intentions? This is a question we often have to ask, with the general consensus depending on both how effective the supposedly poorer writing is in contrast to the aims of the story, with a relatively equal divide between films that live up to its potential, and those that are squandered by mediocrity. For the first act of Three Months, it seemed like it was going to lean towards the latter, mainly as a result of the stilted dialogue that felt generated purely for the purposes of reaching the quota needed for a meaningful teen drama about deeper issues. The directorial debut of Jared Frieder does have a lot of promise, especially in how it handles the message behind the story. It focuses on a young man who decides to express his rage at the world through an anonymous sexual encounter, which leads him to come into contact with HIV, prompting him to immediately be tested, only to find out that it will take 90 days to determine his status, during which time he is forced to confront certain deeper issues about his own identity, as well as that of the people who surround him, many of whom are going through similar existential crises. After a rough start, and some writing that was in dire need of a critical glance, the film becomes quite moving, gradually emerging as one of the more refreshing social issue dramas of recent years, and providing evidence for Frieder as a filmmaker who not only has something to say, but also possesses the talent to do so with finesse, elegance and an abundance of humour that helps us look beyond the flaws.

Three Months is not a revolutionary film, which is something we do need to keep in mind when it comes to discussing queer cinema. There’s a tendency for films centred on issues relating to the LGBTQIA+ community to be comprehensive, filled to the brim with social commentary and well-polished discussions on these important matters, with the gall to not include every potential talking point is seen as failure. Naturally, if we look at these films from that perspective, anything vaguely less-than-perfect will be seen as inferior. A film like Three Months simple wants to explore a deep set of themes through the lens of a very charming and upbeat comedy, rather than being an all-encompassing critique of social and cultural perspectives. In this regard, it does succeed, and it makes it clear from the very first moment that this is not a film that intends to be anything other than a sweetly sentimental coming-of-age story, which just so happens to centre on discussions around issues relating to HIV. In many ways, choosing to approach such a theme from a place that is much more gentle and humorous may seem flippant, but the film certainly never makes light of the grave subject matter, instead approaching it from a place of more earnest sincerity, just using comedy as the vessel to get this message across, since audiences tend to respond more intensely to the works that keep us invested, and while Three Months may be flawed in many ways, it doesn’t feel like it is showing anything other than the utmost respect for the material, which is much deeper than those more unstable first few scenes may lead you to believe.

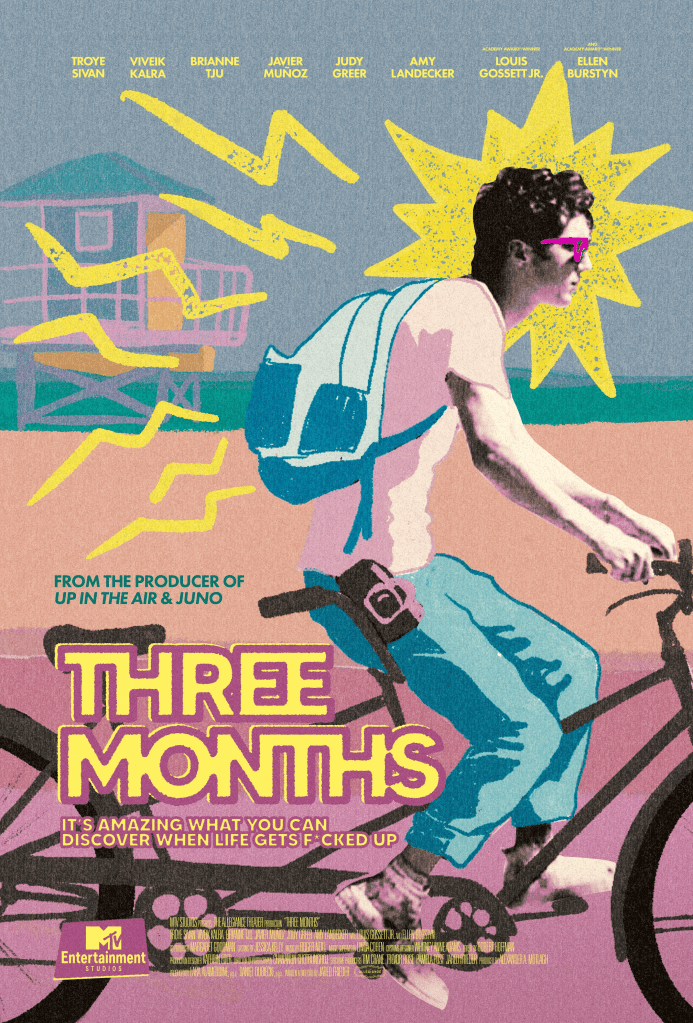

One of the more interesting quirks around Three Months is that it features a leading performance from Troye Sivan, who is certainly not a stranger to the medium, having started out playing the titular character in the moderately well-received adaptations of the Spud series of coming-of-age novels, but who swiftly moved onto pursuing music as his primary career, with acting appearances becoming more sporadic the further he came to be seen as more of a singer and songwriter than an actor. Undeniably, he’s not the most polished actor – his American accent was inconsistent and strained, and there were far too many moments where the mechanics of his performance were glaringly clear, almost to the point that our investment in the character began to wane. However, what Sivan lacks in polish, he more than makes up for in earnest energy – he commits wholeheartedly to taking on the role of Caleb, a self-destructive young man who is growing tired of being lonely, and turns in a strong performance that suggests that he still has that special spark that kickstarted his career. It helps that Sivan is surrounded by some tremendous actors in their own right – the legendary Ellen Burstyn and Louis Gossett, Jr. play his grandparents, having relatively small roles that still leave a profound impression, since they’re both give exceptionally moving moments, proving to be the heart of the film. Three Months smartly disperses its serious conversations amongst a wider group of characters, never placing the burden on one to carry the brunt of the more sobering discussions, and instead allowing its entire ensemble, both newcomers and veterans, to turn in strong work.

However, as much as we wax poetic about the form, Three Months is a film driven less by the idea of being entertaining, and more by the desire to have very frank discussions. HIV may not be the death sentence today that it was in the 1980s, but it still requires sensitivity and honesty when a piece of art addresses it, because while medicine has made enormous leaps to give those who have been infected with the virus a much better standard of life, it is still a disease that carries with it both physical challenges and social stigmata, both of which are explored in-depth throughout this film. Unlike works produced a few decades ago, the story doesn’t centre on the panic surrounding the disease – if anything, the frequent occurrence of the term “you’re going to be fine”, directed at the main character as he awaits his result, are reassuring, especially since the vagueness in the statement implies that, regardless of the result, he is going to get the help and support he needs to live a fulfilling life. The film uses that ambigious space between moments, where we patiently await our fate, and focuses on how these days and weeks can be stretched to the point of being nearly unbearable, with the psychological strain of not knowing what is going to be contained within that ominous envelope being one of the biggest challenges when it comes to these discussions. The film is always forthright and honest about its intentions – it never once comes across as insensitive, and takes an active role in showing that it’s often easier to handle such difficult conversations with the right support system, and the moral and mental fortitude to work through it. It’s a powerful film when we approach it from a place of genuine good faith, and even at its most unstable, there is a mystifying beauty to the film and its message.

Three Months may occasionally be overwrought, and its handling of the material can be considered heavy-handed, to the point where it struggles to establish a particular tone, and can often feel like it isn’t entirely sure of what it wants to be in the first place. However, it is admirable the extent to which it shows its willingness to risk alienating viewers by being very honest about its intentions. These discussions may be difficult, but they’re necessary, and as much as the film is often weighed down by its flaws, it never feels like it is aiming at anything other than telling a beautiful story of a young man discovering who he is while waiting to discover if a moment of poor judgment derailed his life completely. Interestingly, considering Three Months is focused on a protagonist desperate to not have the entire course of his life changed, the fact that it does become entirely different is beautifully ironic, since (regardless of the test results, which he sees as the destination after this excruciating journey) he learns so much about himself and others on the way there. It’s a simple and very funny film, but it has an abundance of heart, and a spirit of genuine adoration for its characters, both in the people they represent and the circumstances that inspired this melancholy story. It’s not the best film to tackle these themes, but it is one that starts the conversation, which ultimately means much more when we look at it from afar. It normalizes having serious discussions in a way that doesn’t imply a near-apocalyptic mindset, and it carries itself with a genuinely earnest sense of endearing beauty, which makes for a lovely and motivating piece of contemporary filmmaking that only adds to a steadily-growing body of works on the issues surrounding the queer community.