Paddy Considine is one of those actors who many of us recognize, and whose presence we often appreciate, even if he’s not someone whose name we immediately can recall. However, he has proven himself to be a very gifted artist on countless occasions, to the point where his first attempt at stepping behind the camera yielded incredible results, mirroring his success as an actor and proving he is one of the most talented creative forces in contemporary British cinema. Tyrannosaur is widely considered one of the greatest directorial debuts of the previous decade, an ambitious and heartbreaking social realist drama that Considine wrote and directed, expanding on a short film he had made years before, the story of which serves as the general foundation for this film. It’s difficult to argue with the effusive praise that is often heaped upon this film – Tyrannosaur is just as brilliant as its reputation would lead you to believe. It is a shocking, heartbreaking story of two wayward individuals finding each other at the most opportune moment, when both of them were in dire need of a spiritual companion to help them in their daily challenges, someone to share a drink or a fond memory when it was necessary, or simply to be a shoulder to cry on when it was needed most. With this film, Considine consolidates himself as one of the brightest filmmakers working in cinema today, someone whose perspective isn’t only fascinating, but seemingly essential, and whose unique voice carries Tyrannosaur to a place of profound meaning that strikes us with deep and unequivocal intensity.

From the outset, we know that Tyrannosaur is not going to be an easy film – it begins with one of the main characters brutally (and without reason) killing his own dog in a fit of rage, which only forces him into an even deeper spiral of depression and erratic behaviour. Considine, who is mostly recognized for his more comedic work as an actor, clearly did not have any interest in playing it safe when it came to making this film, ensuring that every moment, while uncomfortable, contains some deeper message. The director has spoken about how much of what inspired this story comes from his own experiences growing up in the English Midlands, the people he encountered in his earlier years forming the foundation for the characters that populate this film. It’s always an interesting approach when a director takes inspiration from their formative years in crafting a film, not necessarily making something that could be called autobiographical in the traditional sense, but rather having nuances that could only come from first-hand experience. Considine truly infused every frame of Tyrannosaur with the kind of heartful dedication that many filmmakers struggle to convey, using the platform less as a way of only telling a story, but also establishing a particular mood and atmosphere that allows him to frequently explore deeper conversations surrounding the central themes that inform the film, while allowing it to remain as beautifully and quintessentially human as it was intended to be in the first place.

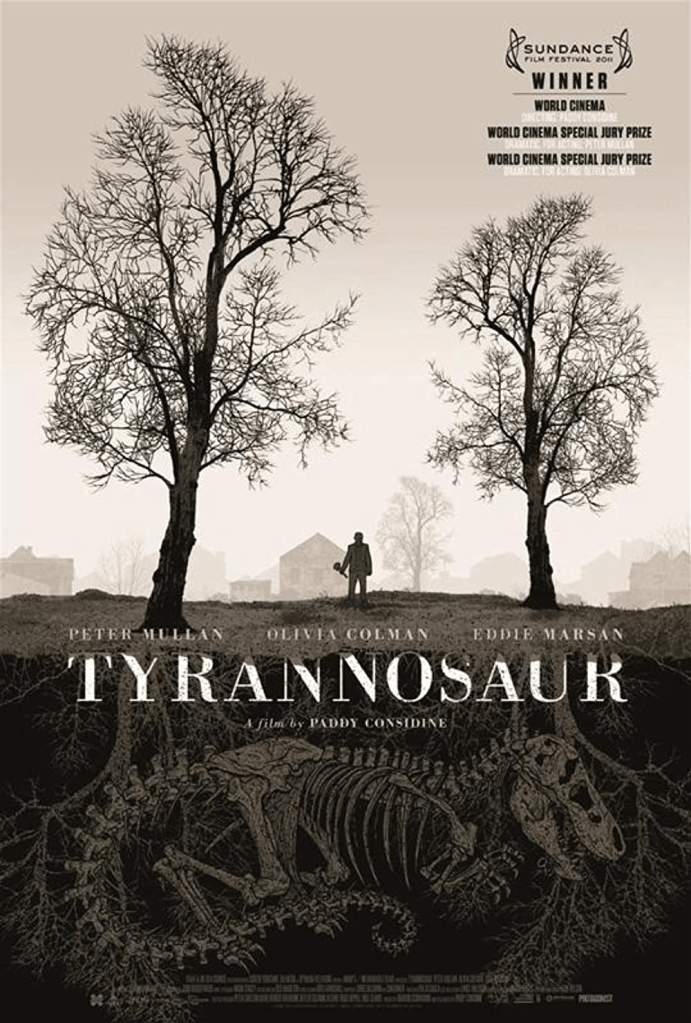

The aspect that first drew our attention to Tyrannosaur, beyond the fact that this was the directorial debut for one of Britain’s most cherished character actors, was the performance given by someone else who not only matches that description, but has continuously defined it. To call Olivia Colman a national treasure seems both reductive and inappropriate – she is an actress who has frequently proven herself to be capable of nearly anything, going from scene-stealing supporting roles in comedies on both television and in film, to one of the most fascinating actresses of her generation. However, while it is easy to suggest that her work in Peep Show or Hot Fuzz was her breakthrough moment, it was Tyrannosaur that finally made the global audience stop and pay attention to Colman – suddenly, this lovable comedic force of nature was going in a completely different direction, delivering a harrowing and heartbreaking performance as a victim of domestic abuse, who does her best to escape a difficult situation, but to very little avail. Colman’s work in this film defines the concept of a revelatory performance, since she reconfigures everything audiences had expected from her, and redirects it through the lens of a more serious, sobering perspective that is still staggering today, even after the previous decade has shown that Colman possesses enough range to play any role, and remains her finest screen performance to date, which is an impressive achievement considering she has spent several years honing her craft in a range of incredible projects that showcase her endless array of gifts. She is beyond excellent in Tyrannosaur, so much that not even Peter Mullan (who is extremely talented in his own right, turning in some of his own greatest work here as well) is able to draw attention away from her, despite this film being designed as a two-hander to showcase the incredible talents of two of Britain’s greatest performers.

Tyrannosaur is a film that is perpetually challenging the audience, whether it be to look within and question our own humanity (since the film positions two very complex characters with notable flaws as its protagonists, never allowing them to get away with their actions, even if there was a reason for them), or to glance around at the world that surrounds us, noticing the inherent shortcomings that pervade even the most idyllic aspects of society. This film has often been compared to the kitchen-sink realism movement that was defined by the likes of Ken Loach and Mike Leigh, both of whom linger as spectral inspirations behind the story – but even to reduce it to just being a gritty social drama seems like it isn’t giving Considine the credit he deserves, since his intentions are far more than just to represent the reality of these characters in an objective, unfurnished manner. Throughout Tyrannosaur, we are witness to a series of conversations between two characters who are lost in a world they no longer recognize. Each discussion brings them closer together (even when the tone that surrounds it is more combative, and intentionally so), and forces them to perceive the world in a slightly different way after having garnered small but valuable insights into how another person sees it. As mentioned above, this film is designed to be a two-hander in terms of offering duelling perspectives, and Considine makes use of the simple structure well – he constructs an intimate, revealing portrait of a time and place, and the characters that inhabit it. He focuses less on exploring the social milieu from an objective perspective, and instead filters the working-class malaise through the differing perspectives of a couple of lonely people drawn together by their lack of understanding of an environment that is both hostile and inescapable. The only salvation is to find someone to help them through it – and the director digs exceptionally deep into the psychological states of these characters in pursuit of deeper, more complex meaning that is entirely unexpected based on the simple nature of the film when taking that initial cursory glance.

It takes time to ease into Tyrannosaur and fully grasp the scope of what Considine is doing with this film – and even in its most lighthearted (which are few and far between, existing only to break the shocking tension that persists throughout the film), the story is sobering, and perhaps even quite terrifying, since it presents a very difficult side of the human condition, one where it would seem like our default state is to be violent, manipulative and erratic, with only a few individuals managing to show some kind of compassion, which is ultimately the central storyline of this film. Tyrannosaur tackles some very deep themes – domestic abuse, addiction and mental health are all factors in this story, and Considine explores each and every one of them with a kind of spirited candour that points towards his inherent fascination with the psychology of the ordinary person. It can be a difficult film to watch, and the subject matter can be repulsive or overwhelming for those who aren’t prepared for the depths to which the director is willing to dive for the sake of telling this heartbreaking story. However, once we can move past the shocking subject matter and start to focus on the actual narrative, and the message contained within, Tyrannosaur becomes an absolutely stunning experience, a heart-wrenchingly beautiful ode to the working-class citizen who does their best to survive, and proving that beneath even the harshest exteriors lurk compassionate and generous souls that will be willing to help those in need, which manages to give this film a sense of hope, which is essential to the experience, since it balances out the cynicism and ultimately makes this film an extraordinarily complex but beautiful voyage into the lives of ordinary people and their individual challenges, whether small or enormous, that they face on a daily basis.