Purely on his contribution to the medium, Ralph Bakshi deserves to be considered one of the greatest animators in the history of cinema. His name may not be as well-known as some of his predecessors, contemporaries and artistic descendants, but his legacy has remained almost entirely untouched as possibly the most significant elder statesman of adult-oriented animation. The qualities that made his work so brilliant either come in the sheer ambition of the texts he occasionally tasked himself with adapting – this is the same genius who took on both J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, and R. Crumb’s Fritz the Cat, taking them from the page and turning them both into cinematic masterpieces, or the audacity of his original works, which pushed the boundaries of the artform to previously unprecedented heights. This is a good introductory analysis to Cool World, the director’s final completed feature film, and arguably one of his most ambitious, if solely on the nature of the narrative and the scope of what Bakshi was aiming to achieve here. It’s a peculiar work, but one that has a lot of value, both in its artistic underpinnings, and the director’s methods of consistently questioning and interrogating certain subjects that weren’t entirely new to him as a filmmaker, but certainly not what we’d normally expect from one of animation’s greatest provocateurs. Cool World is a fascinating document of a film, and one that is actually much more than just the sum of its parts, particularly when we look beyond the unconventional nature of the story, and begin to appreciate the exact qualities that make this such a groundbreaking piece of cinema that deserves a much wider span of recognition.

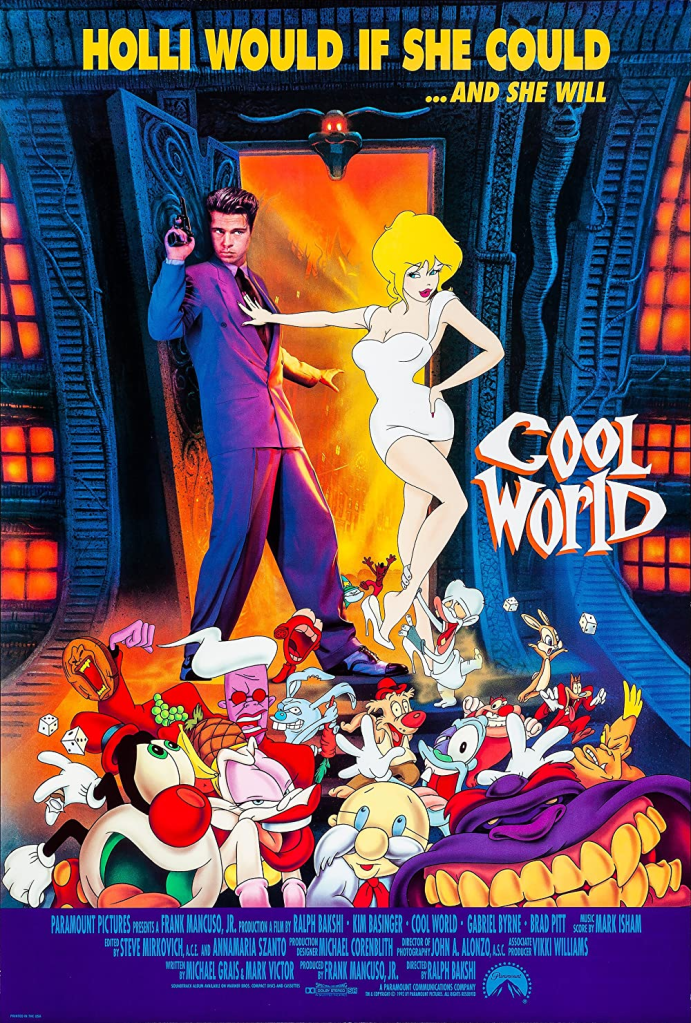

If we were to describe Bakshi and his work in only two words, they’d likely be “independent” and “revolutionary”, his films exemplifying both concepts frequently, even if the final products can sometimes be exceptionally controversial – but this is exactly where his legacy stands the firmest, with his outright refusal to buckle to the conventions of mainstream animation making him someone whose entire career was driven by a persistent need to create alternative forms of animation, targetted to those who exist outside of the audiences normally seen as the ideal demographic for major studios. Cool World is perhaps not the best film to discuss this particular issue, since it is Bakshi’s attempt to do something slightly more high-profile, mainly through the casting of a trio of recognizable actors (with Kim Basinger, Brad Pitt and Gabriel Byrne being unexpected but welcome collaborators into the director’s world), and also the unconventional structure, which saw Bakshi working significantly in the realm of live-action for the first time. In terms of the story, there is a less focused approach present in the film, but in terms of spirit, this is quintessentially the work of the esteemed rebel, whose artistic ambitions are still as notable as ever, just replaced with a softer approach to the narrative process, which ultimately makes Cool World a different kind of experience as a whole, especially in how Bakshi deconstructs some of the more distinct themes, which are rendered in vibrant colour, proving that age may have weathered his perspective, but Bakshi’s passion was still as strong here as it was when he was shattering artistic barriers in the 1970s.

Cool World is also arguably the director’s most experimental work, solely based on the fact that it was his most audacious in the form of it being a hybrid between animation and live-action, something that had been explored previously in bigger films, but not by Bakshi himself, who normally stuck to experimenting within his own medium, rather than crossing over. What often happens when a director known to work almost exclusively in one style of filmmaking temporarily tries something entirely different from what they are known to do (such as a documentarian directing a narrative feature film, or vice versa), is that we tend to view it as an outlier, and thus apparently should be treated as such. This is unavoidable, but also oddly dangerous, since there is a genuine sense of curiosity that has persisted across the director’s work that is impossible to remove from this film – it’s the smallest details that make his films special, and Cool World is not an exception. Here he was questioning a few more complex issues, particularly in regards to the artistic process, which is something that he knew inside and out, considering he was a notable journeyman when it came to ensuring that he was involved at every stage of his films, being one of the purest auteurs imaginable. The filmmaking here itself is remarkable – the blend of animation and live-action footage may not be the smoothest, but these clumsier moments add depth and nuance to a film that really benefits from the more jagged charms that constantly defined Bakshi’s career – the lack of polish adds character, even in a film produced decades after his debut.

The fact that Cool World was Bakshi’s final completed feature-length film is unfortunate, but also rather fitting – after all, this seems to be the director reflecting back on his earlier years as an artist, where films like Coonskin and Fritz the Cat were courting controversy with very little hesitance. As one of only a few films the director made that wasn’t rated R, but rather given a more accessible rating, it’s clear that Cool World was made for a wider audience. This is a more self-referential work, a film that sees the director focusing on a few vital themes that he had not addressed in earlier films, whether they were not of interest, or because many of them had to do with the discourse that surrounded his craft that emerged after his peak. Cool World is a film that is built from the director’s very clear interest in exploring the art of animation – the story centres on the boundary between reality and fiction, and where the primary character is a cartoonist known for works he produced during his heyday – there’s certainly a sincere degree of self-referential humour in this aspect of the story, and it can be really delightful when it is executed well, which is exactly where it succeeds. This does feel like a film that will constantly be seen as more of an attempt to do something different, but not necessarily in a way that detaches it from the rest of the director’s work – in many ways, Cool World feels like a film that is in dialogue with his previous films, touching on issues that o

An absolutely sensational dark comedy that is the culmination of decades of precise and groundbreaking animation, Cool World is an artistic achievement that warrants notice and a critical reappraisal, since this kind of ambition is seen once in a generation – and considering this essentially signalled the end of Bakshi’s most productive period as a filmmaker (having spent the previous three decades working in short films and on television, as well as trying to complete his most recent passion project, Last Days of Coney Island, which seems to have faded into obscurity after a brief moment of seemingly coming to fruition in the way the director intended). It’s tough to not read some metafictional commentary into this film, especially when Bakshi is making it resoundingly clear that what he’s doing is looking back on his past experiences in the industry, and crafting a film that almost feels like a passing of the torch to the younger generations, who took inspiration from Bakshi, who has now since retired, but passing his legacy onto a new set of rambunctious storytellers in the medium. Alternative and independent animation are at their peak, with far too many filmmakers to name being the heirs apparent to Bakshi and his style of transgressive, experimental storytelling that proved that pen and paper can produce some of the most stunning results, granted there is some degree of drive and ambition behind it – and they certainly do not get more audacious than Cool World, a film that takes risks and may not always land perfectly, but its how it still manages to be entertaining and subversive that makes it such a daring and brilliant work that is never afraid to take the leap into the unknown, since it knows that there will be something of value on the other side.