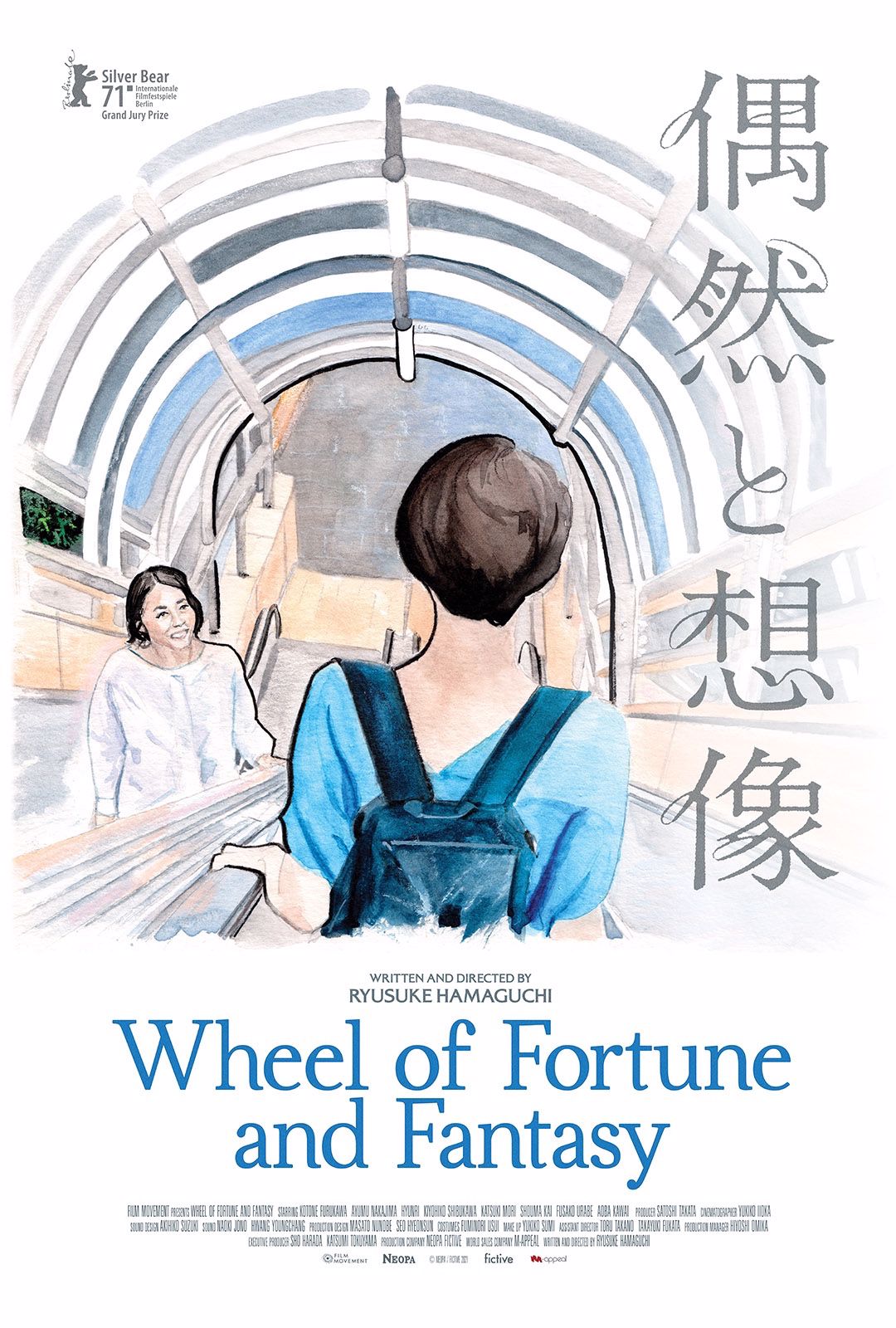

The reappraisal of Ryūsuke Hamaguchi as not only one of the most interesting directors working in his native Japan, but one of the most important artists of the current generation on a global scale has been wonderful. He has been working steadily for over a decade, but has only recently managed to achieve a level of recognition beyond those who just associated him with films like Happy Hour, which was most known for its running time of over five hours. Having amassed something of a following, Hamaguchi has essentially been given the freedom to tell the stories that he has always been interested in exploring, such as in the case of Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy (Japanese: 偶然と想像), his attempt at an anthology film, and the first of two major productions for which the director was the helm this year, proving both his impeccable work ethic and versatility as a filmmaker. Composed of three distinct, separate stories set in contemporary Japan which share a few common themes (some of which are not clear until the end, when the director manages to covertly tie them together in ways that the unsuspecting viewer may not have expected), the film is a masterful character study that ventures into the psychological state of three women as they negotiate with their environment, trying to make sense of a peculiar world that they clearly struggle to comprehend in one way or another. It’s an intricate film that carries a lot of weight, even more so when we are given the opportunity to walk away and ruminate on some of the primary themes, and it only proves what a true master of his craft Hamaguchi is, with every frame of Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy being composed from the same sensitive curiosity that has always propelled the director’s career, combing a range of very interesting elements into this charming and poignant glimpse into the human condition.

Simplicity is one of the first qualities we notice when looking at Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, particularly in how Hamaguchi, avoiding several of the more notable cliches that come with the genre, manages to tell three very interesting stories. With many anthology films (particularly those that are extremely compartmentalized, not having a clear framing device that surrounds them and ties them all together), the short-format structure of storytelling, where we spend only a small amount of time with these characters, is easy to mishandle. It’s tempting to compress an entire feature-length film’s worth of material into a quarter of the time, which leads to many anthology films being difficult to discuss, since either their ambitious ideas are not realized enough (as a result of nothing enough time to develop), or because they’re simply too different to find a coherent thread that flows through each of them, which is a vital component of successful entries into this genre. Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy is a very logical and well-crafted film, undoubtedly as a result of Hamaguchi’s work as both a director of his own films (both narrative features and documentaries, which populated the earlier part of his career), and as a screenwriter. He demonstrates a clear and concise ability to plumb for the most meaningful content in his stories, extracting only what is vitally important and leaving the rest to the viewer’s imagination, being ambigious enough to evoke conversation. This not only adds value to the film, since it demonstrates a keen understanding of the primary themes (so much that it doesn’t need to elaborate on them to the point of becoming prosaic), but also allows the audience to draw our own conclusions and engage with the material in our own way, which is always a wonderful experience for those who enjoy being given the chance to develop our own interpretation and understanding of the universal themes found at the heart of the film.

Hamaguchi is most appropriately described as a simple storyteller, weaving together interesting narratives that may seem complex in theory (both in terms of style and substance – he is not someone we can consider particularly interested in brevity, albeit being one of the few filmmakers who receives the benefit of the doubt when it comes to multi-hour cinematic odysseys), but are actually quite straightforward. While they do sometimes require us to think outside of the box, perhaps even stepping away from the heart of the story and instead analysing it from afar, they’re never convoluted, and they carry a potency that is best understood when we consider them as simply fragments of the human condition, carefully pieced together by a filmmaker with a profound interest in artistic representations of the smallest and most inconsequential minutiae of everyday life. Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy is one of the most exceptionally well-crafted anthology films of recent years, since it is not solely three individual stories thrown together (which is a common tendency for anthology films, where they are clearly the product of a filmmaker having some strong ideas, but not enough to qualify for a feature-length project), but rather an actively engaging triptych that looks into the lives of several individuals in contemporary Tokyo as they navigate various challenges. Hamaguchi manages to not only construct these individual stories as compelling, pieces all on their own (each one of them can stand alone as an impeccable short film), but ties them together in a way that is cohesive and meaningful, revealing small details about each of these characters, which eventually compounds into a vivid portrait of humanity, each one of the individuals in these stories representing a different kind of personal struggle, their quandaries seeming to be very specific at first, but eventually flourishing into the realm of universality. It’s impossible to watch this film and not feel the sensation of desire, uncertainty and existential curiosity, which the director perfectly encapsulates within each story, and then brings together in the audience’s mind, as we look at these narratives and begin to subconsciously draw these conclusions all on our own.

As a result, each individual story is extremely different, but united under a few common themes. One of Hamaguchi’s most distinctive qualities is the ability to be descriptive but not heavy-handed. His films tell stories of his native Japan, whether in the past or present, and focus mainly on ordinary individuals, rather than those of some level of importance. As one of the artistic descendants of filmmakers like Yasujirō Ozu and Mikio Naruse (the latter being someone that the director has explicitly cited as a major influence, which is clear through his work), Hamaguchi understands the value of a more simple view of life. Nothing necessarily needs to happen for a film to be engaging, and while it’s incorrect to say that his stories are filled with banalities, he doesn’t go in search of narrative elements that don’t make sense within his pared-down, simple perspective as an artist. He is one of the rare filmmakers that can make an entire film just out of two actors in a room, having a discussion, since there is always deeper meaning in the dialogue, proving that human interaction, even at its most fundamental form, is constantly interesting and worthwhile when made correct – and this is extremely clear throughout Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, which finds existential value in the most unexpected places. Deeply philosophical in his approach, but never overwrought in the sense that some of his more grandiloquent contemporaries may be, Hamaguchi has a keen eye for the smallest details, and manages to construct three stunning stories out of his curiosities. Whether it be a young woman questioning her love for a boyfriend whose infidelity has torn them apart, or one who is willing to put both her professional aspirations and personal life on the line for a friend, or someone who simply transposes her own longing onto a stranger, each of these stories presents us with complex protagonists that both exist within a recognizable version of our world, as well as outside of it.

Characterization is vitally important to a film like Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, which is built almost entirely on the performances. Hamaguchi does not rely on directorial flourishes, and instead presents the audience with a strong script, and a group of gifted actors tasked with bringing it to life. Choosing a standout from this cast is almost impossible, not only because everyone is excellent, but because there is such an even division of weight between the four main protagonists, as well as the rest of the supporting cast. Each actor delivers stellar work, but the majority of attention goes to Kotone Furukawa, playing the protagonist of Episode 1: “Magic (or Something Less Assuring)” (a young woman questioning her past relationship), Katsuki Mori, who is the gifted young woman seducing a much older university professor, played by Kiyohiko Shibukawa, in Episode 2: “Door Wide Open”, and Fusako Urabe and Aoba Kawai, who lead Episode 3: “Once Again”, the two-hander that concludes the film, telling the story of two wayward souls that encounter each other in what appears to be a coincidence, but turns out to be something much closer to fate. It’s a fascinating blur of fiction and reality, and the actors are fully-committed to leaping directly into the heart of the film, occupying these roles and closely following the director’s vision, which is much more comprehensive than it would appear at the outset. There are some beautiful performances contained within Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, which thrives on how compassionate it is, carrying a sense of sincere humanity that propels the film and single-handedly makes it such a gorgeously poetic ode to existence.

Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy is such a charming film, it seems almost impossible to not be absolutely engaged by what we’re seeing presented to us throughout this wonderful work of humanistic art. Hamaguchi is a true master of his craft, having developed into a visionary who is capable of weaving together small details that, when pieces together, create a stunning portrait of the human condition. It may seem like a relatively minor work in theory, since we see several anthology films centred on either specific cities or on the theme of love, produced often – but none of them are as vivid as this one, which does not anchor itself within a solitary theme, but rather riffs on a few different ideas, many of which are directly related to the idea of love in its various forms. Whether questioning past, present or future romances, as well as those that never came to fruition, Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy looks deep into the lives of some truly ordinary people, who are rendered as fascinating individuals when Hamaguchi endeavours to tell their story, and grounding itself within a kind of ethereal magical realism, the film is a captivating endeavour that never quite answers all our burning questions, but instead tells us exactly what we need to know, not wasting a single moment on unnecessary ramblings. It takes its take, moving at a measured but compelling pace, and emerges as one of the most deeply sincere and meaningful deconstructions of some of life’s most notable challenges, all tied together in this astonishingly endearing, complex and melodramatic anthology that proves that anything is possible with strong ideas and the artistic vision to put it all together in a format that is both compelling and enthralling, one of the most incredible strengths of Hamaguchi, a director I am comfortable calling one of the very best working in cinema at the present moment.