When it comes to classics of the western genre, you can’t really go wrong with High Noon, the fascinating film by Fred Zinnemann, who directs the story of a semi-retired US marshal who is forced to defend his town (and his honour) from the encroaching danger of a gang who are in pursuit of revenge after he sent them away to prison years before. Undeniably, this is a film mainly designed for those who are already proficient in the genre, since it’s doubtful that High Noon will make a convert out of anyone who isn’t already committed to western films, being very much a traditional film along the lines of the John Ford and Howard Hawks classics (amongst others) that reigned supreme at the time. As a result, some may find this film somewhat dull and lifeless, which is a perfectly understandable reaction, since not everything in this film always works – the performances are pretty conventional, and the story itself is quite derivative, even if there are a few interesting moments peppered liberally throughout. Ultimately, High Noon is a worthy entry into a genre that was at its peak during this time, but it’s important to note from the outset that there isn’t much about this film that stands out if someone isn’t already well-versed in the genre, since there’s a degree of familiarity with western filmmaking that is needed to fully-embrace this film, and as someone who is often quite apprehensive when it comes to classic-era westerns, this film was a slight challenge at times, even though it does have some terrific ideas embedded at its heart.

A lot of appreciation for this film comes from understanding the ebb and flow of the western genre, which thrived on a particular formula, at least in terms of this particular era. Zinnemann, who is a director who made solid films that could range from towering to exorbitant, depending on the project, isn’t someone we’d immediately expect to be entirely adept at working in the genre, but he does bring his own distinctive touch, albeit one that was still being refined, as he was developing his style that would only reach its apex in the following decade. High Noon is a fine film, but one that requires us to be willing to follow this very conventional story, and believes every moment of it. Unfortunately, for those seeking something a bit more ambitious, the film may not always harbour exactly what we’re looking for. As reliable a director as he may be, Zinnemann could only do so much with the material, and whatever fragments of promising originality exist are used up in the first act, which is intriguing enough to keep any viewer engaged, regardless of their appreciation for the genre. Instead, it’s the rest of the film that is divisive, creating a situation where we either become thoroughly invested in this story and yearn to see it through to completion, or we just become disinterested in what is essentially a by-the-numbers western drama. There’s very little room to make arguments for a middle-ground between the two, which only proves how this genre has always been one that polarizes audiences, the contemporary perspective proving that such stories can be told without losing the viewer’s attention, which is essentially what this film struggles to avoid.

High Noon is a very effective litmus test to determine if someone can look beyond the conventions associated with the western genre and embrace what is essentially a style of filmmaking built on a particular process. Not taking into account the directions the genre would go, and the fact that it would spawn a number of off-shoots in subsequent years, the film is a very traditional one, but still tries to approach the material in a different way. Part of this can be found in the execution of the story – some have praised High Noon for being one of the most character-focused westerns of its era, where the emphasis is placed on the individual at the heart of the film, rather than the spectacle of the filmmaking. However, when you consider the film is structured as 70 minutes of exposition (which finds the main character essentially just conversating with several different people), followed by a few minutes of thrilling action, it seems like diminishing returns. At only 84 minutes, High Noon is a breeze to get through – but this is a case where brevity may not have been beneficial, since so much of this time is spent establishing the story, not enough is given to the moments that everything was leading up to. By the time we reach the climax, we’ve been so thoroughly exhausted by the constant discussions had throughout the film, we can’t ever really enjoy the moments designed to exhilarate and entertain – it doesn’t remove the merits of the film, but certainly doesn’t add much to the proceedings either, leaving this film squarely in the middle of a genre that often struggled to exist beyond tradition.

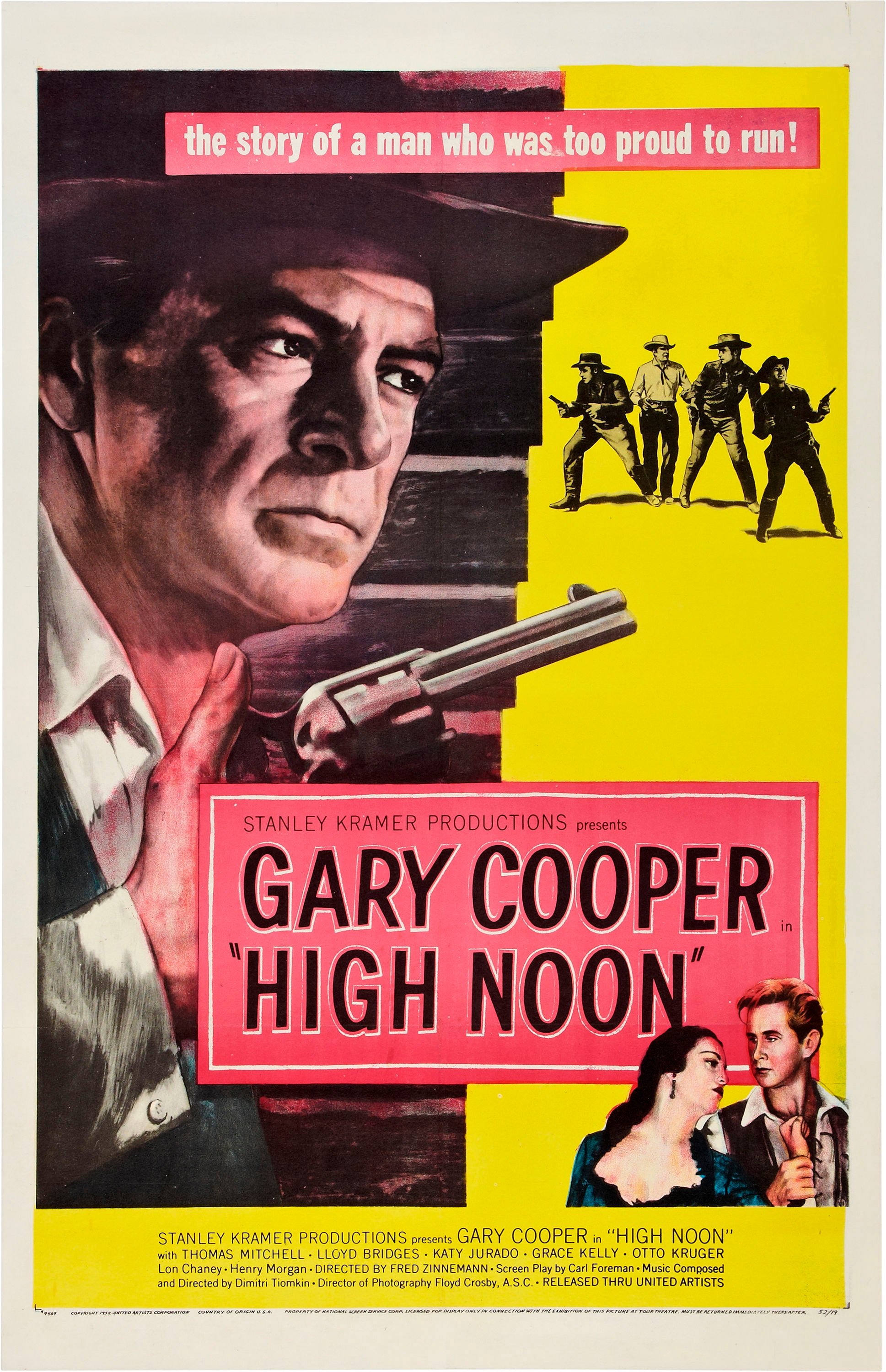

Of the aspects that are almost universally praised when it comes to High Noon is the performance being given by Gary Cooper, in one of his most iconic roles. Arguably not an actor who ever embodied the concept of subtletly or nuance, Cooper was a star who often struggled to move past very broad strokes of acting. In most instances, this would be a liability, but when you’re dealing with a character like US Marshal Will Kane, it helps to have an actor as grandiose as Cooper, since it aids in constructing the character as far more than just an ordinary hero. However, the most interesting performances in High Noon are those that occur around Cooper, who is really just a vessel for Zinnemann to showcase the very impressive supporting cast he assembled – Thomas Mitchell, Lloyd Bridges, Grace Kelly and Katy Jurado all prove how this film is far from being solely dependent on Cooper, who often fades into the background while some of his more interesting co-stars take the stage and deliver very passionate performances that almost imply that this film is going to be better than it actually is. As a character-driven piece, High Noon could have developed itself a bit more than simply following the same pattern of using archetypes, but the performances are solid enough for this to be excusable, at least in terms of how the film develops beyond a certain point. The story itself may be quite derivative, but the performances hint at something much deeper, even if this potential isn’t ever realized beyond these brief implications that suggest a much more complex film lurked beneath the surface.

High Noon is a fine film, but one that really works best when we take it as yet another iconic western that doesn’t extend too far beyond the fanbase normally associated with the genre. It’s the kind of film that thrills those who love the genre, while being somewhat tedious to those that don’t particularly enjoy it, making for a film that can be considered quite divisive, despite its relatively well-regarded status. It is never necessarily bad, since it is well-directed and has some very solid performances. Instead, it’s just a case of it sticking so close to convention and refusing to take any real risks that impact the film and make it such an underwhelming experience for those who want something more from what appears to be a very promising story. The technique of telling it almost entirely in real-time had potential, and it did yield some interesting results (although one would hope that they’d use this time better than to just have the main character walk through the town looking for deputies to accompany him on this mission), and it does make for a relatively thrilling film when it reaches a point of action rather than exposition. As a whole, High Noon is perfectly decent and earns its status as a relatively iconic film – it’s just that it doesn’t do much to break out of the genre, which ultimately impacts the effect it had as a film outside of its traditional approach, an unfortunate but understandable shortcoming of an otherwise decent film.