Gene Kelly didn’t direct too many films, but he did make a fair share of great ones. The majority of the ones that he is most remembered for are musicals (often co-directed by close friend and collaborator Stanley Donen, who worked with Kelly to make some of the greatest entries into the genre in history), which is only logical, considering he is arguably the greatest showman in the history of cinema. However, it’s the more minor efforts that are sometimes most interesting when it comes to assessing the career of a Hollywood icon like Kelly, including his directorial ventures outside the musical genre. A gifted filmmaker in his own right, he made a series of fantastic comedy films, many of them orbiting quite close to the set of urban conventions that he mastered over the course of his long career. One of the outliers is The Cheyenne Social Club, the director’s attempt at making a western, and one of the most subversive films of that period. Produced at a time when revisionist westerns were no longer a new craze, but rather the logical direction in which the genre was heading, there is a lot of value in what Kelly was doing with the material, taking the script by James Lee Barrett (which had merit on its own), and turning it into a lavish, endearing subversion of western conventions, facilitated by someone whose ability to take any genre and make it his own remains undefeated. Not the most well-known film, both in terms of Kelly’s career as a director, and in the genre as a whole, The Cheyenne Social Club has attained the status that is almost preferable for a film such as this, a hidden gem that not many know about, but those who do cherish it endlessly, enough to make this a fascinating footnote on a genre that has seen nearly every conceivable twist and turns asserted on it, but yet still manages to find entirely new ways to entertain the audience.

While it is technically a western, a genre in which he had not previously worked (neither as an actor nor a director), The Cheyenne Social Club features all the elements of a classic Kelly film. Primarily, while it may take the form of a western, the film is mainly a comedy – while these aren’t mutually exclusive (with many of the greatest westerns ever produced having some element of well-placed humour), it was designed to be intentionally different, at least at the theoretical level. Secondly, the themes that the film explores are quintessentially amongst Kelly’s more notable traits as a storyteller – his films may be extravagant affairs, but there is also some degree of social commentary embedded deep within them, which makes the experience of venturing into these worlds so enticing. Finally, The Cheyenne Social Club is a lavish, well-composed film that is clearly the product of someone truly passionate about his craft, as he puts together an enthralling two hours of filmmaking that is colourful in both production design and the characters that occupy this world. Kelly himself was not acting in the film (since recent directorial outings seeing him staying firmly on one side of the camera more often than earlier in his career, when he was often the star of his own films – he was seemingly intent on reserving his on-screen presence for the films of others, not a bad choice when the likes of Jacques Demy and Stanley Kramer were seeking his talents), but his enchanting touch can be felt in absolutely every frame of the film, especially those in which The Cheyenne Social Club has to draw on the more heightened sense of absurdity that made Kelly’s work so charming, yet so incredibly layered at the exact same time.

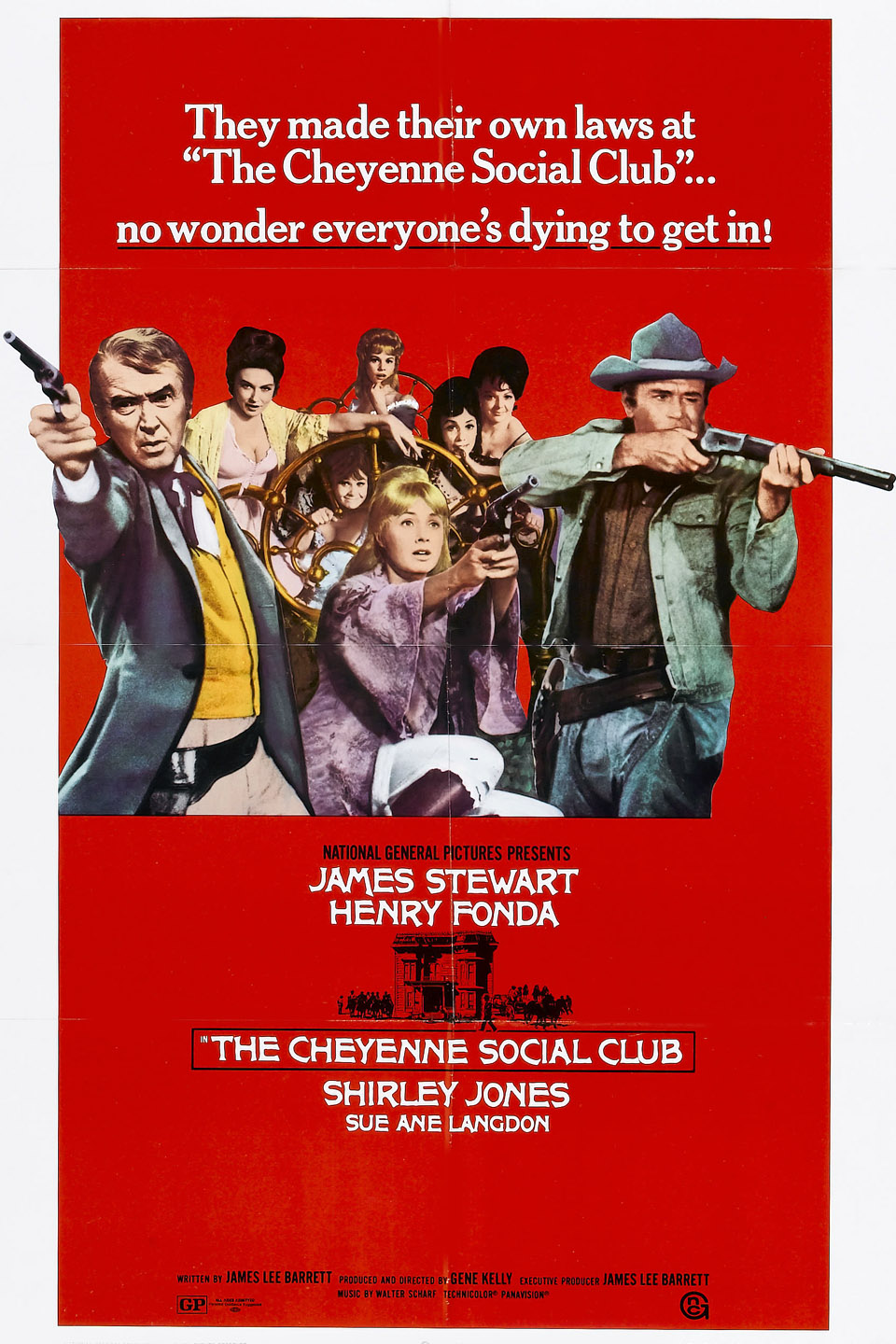

Part of the charm of The Cheyenne Social Club is that this is one of the most bawdy, risque comedies produced by a mainstream studio at the time, and at the heart of the film were two of Hollywood’s most principled and moralistic leading men. The idea of James Stewart and Henry Fonda playing the leads in a dirty-minded comedy about a brothel seems almost absurd, but yet Kelly managed to pull it out of them, not only getting them involved in the film, but allowing them to turn in some of their very best work. Stewart is the simple, decent man who comes into ownership of the brothel, aiming to turn it from a house of ill-repute into one that he can be proud to have associated with his name, while Fonda (who Stewart expressly requested for the role) is his best friend, a more free-spirited individual with a penchant for mischief, which makes his friendship with the pernickety Stewart all the more hilarious, forming the foundation of the film. Both actors make good use of the fact that, despite being older than they were at their peak, that they were still perfectly capable of turning out exceptional performances, and remain as vivacious and youthful as ever, at least in terms of their ability to still provide us with a couple of spirited performances. They’re both firm reminders of the enchanting quality of the Golden Age of Hollywood, something that Kelly worked laboriously to preserve throughout his career, and in the case of The Cheyenne Social Club, a film that is almost melancholic in its nostalgic viewpoint, we have to believe the casting of these two legends was entirely on purpose, especially when the roles could’ve easily have been played by actors half their age – but yet, Stewart and Fonda are better in the parts than nearly any other actor working at the time.

Despite the subject matter, The Cheyenne Social Club is not a film intended to scandalize or shock – if anything, it can be considered slightly too tame, being a bawdy comedy directed from the perspective of someone concerned with the possibility of making something that will ruffle a few feathers. Kelly was never regressive in his artistic viewpoint, but he was the product of his time, so it only makes sense that even a film with this subject matter would carry a degree of gravitas, drawn from conservative values and more puritanical ways of thinking. However, this is where the film is actually most interesting, since Kelly, in the process of putting the film together, infuses The Cheyenne Social Club with a kind of eccentric sophistication, one that allowed him to keep the story elegant, but filtered it through some more questionable discussions. Morality plays a key role in the film – it can sometimes veer towards being exceptionally dark, especially in moments where we see Stewart killing a man (and despite not being the first instance of the genial actor brandishing a gun on screen, it is one of the most shocking), which kickstarts the third-act of the film, and provokes the numerous complex conversations that most may not have expected from a film of this calibre, especially not one that is supposedly designed to be a delightful and exuberant comedy. This is exactly the charm of The Cheyenne Social Club, since despite the darker themes, it remains as buoyant and eccentric as ever, leaning into its idiosyncrasies in ways that may be surprising for many of us, which is all part of the brilliance that was Kelly’s unique perspective, which is much more interesting than many may give it credit for.

As a whole, The Cheyenne Social Club is an utter delight – the gorgeous vistas of New Mexico stand in for the endless plains of Wyoming in the years following the end of the Civil War (which in turn becomes a part of the narrative, with Kelly finding interesting ways to demonstrate how this film depicts the United States as being a country in flux, reflecting the fundamental themes of the story, to the point where these brief implications mean more than any implicit conversations would permit), and the filmmaking is lavish and beautiful, being perfectly handled by a director who valued style, but never neglected adding substance to it. It certainly would be foolish to consider The Cheyenne Social Club to be on the same level of some of Kelly’s more well-known classics, but that’s not an indication of a lack of quality here, but rather that the films were made by someone with such a firm grasp on his craft, anything less than absolute perfection is going to pale in comparison. Undeniably, Kelly was working from a slightly more limited set of ideas, not only working outside the musical genre, but making a western, with which he had very little prior experience. Yet, his work is still impeccable, mainly due to the presence of his two leading stars, who weren’t strangers to the genre themselves, but had the ability to adapt to Kelly’s own unique approach to the western, rather than relying on the tricks they learned from the likes of Anthony Mann and Sergio Leone, who made Stewart and Fonda some of the more interesting actors to ever work in the genre. It’s a tremendously entertaining and insightful film, and one that charms us from beginning to end, showing us a different side of life, while simultaneously giving us all the reason to let down our guards and simply celebrate it and all its bizarre curiosities.