As is the case with many filmgoers, it doesn’t take much for me to get invested in the prospect of a new film by Paul Thomas Anderson, who has proven himself to be one of the most versatile filmmakers working in cinema today. The past quarter-century has been dominated by discourse around his steadily-growing status as one of the more fascinating figures working in the medium today. To be fair, anyone that acquires comparisons to the likes of Stanley Kubrick, Martin Scorsese and (most notably) Robert Altman, is bound to be set up as some future stalwart of the craft. Logically, Anderson is not a perfect artist, and some of his work is less effective than others (despite having never actually made an actively bad film), so the adulation he’s received as an unimpeachable master who can’t make a single mistake is not only misplaced, it isn’t true. If there is one way to describe Anderson, it would be as someone who actively embraces the challenges that come with making a film, working through many complex ideas and not being afraid to acknowledge flaws – it’s what made his earlier works, such as Boogie Nights and Magnolia so fascinating, since they were clearly rough around the edges, but in a way that actually complimented the final product. He’s a filmmaker that centres many of his stories around people that are best described as being essentially works-in-progress, individuals who haven’t quite figured life out yet, but are doing whatever it takes to get there, which is most distinct in the films that launched his career. This brings us to Licorice Pizza, which comes after over a decade where Anderson made mostly very ambitious projects, traversing era and geographical location for the sake of telling complex stories that blur societal values, cultural cues and a wide range of other issues that interest the director – and while it may not reach the impossible peaks of some of his previous films, this one is amongst his most personal, mainly since it sees Anderson making a film about a couple of subjects he knows better than most, leading to a truly pleasant experience with a director we have grown to implicitly trust.

Simplicity is the key to success with the vast majority of films, and with Licorice Pizza, Anderson is returning to his roots, both in terms of the filmmaking style and the subject matter. After a brief sojourn to the United Kingdom in Phantom Thread, the director retreats back to the sun-baked neighbourhoods of suburban California, focusing on neighbourhoods such as Encino and surrounding areas, in his endeavour to launch himself back into the days of his own childhood. Loosely basing the story around the life of Gary Goetzman, a former child actor who made a small fortune through his tendency to hustle, starting a number of businesses that brought him more fame than it did wealth. Taking his cue from films such as American Graffiti (the work that the director has explicitly stated inspired this story), Anderson voyages into the lives of two teenagers growing up in the early 1970s (as well as the multitudes of people who appear in the periphery of their lives), focusing on how they are both stuck at an awkward age, being old enough to understand some of the enormous disappointments and travesties that have shaken their world (such as the Vietnam War and the impact of the socio-political crises on the lives of the most ordinary people), but not old enough to have the gravitas to do anything about it. Fitting in perfectly with some of his other films that focus on the similar concept of the intersecting lives of a wide range of people who share the same general space (in this instance, the urban centres of Encino and its surrounding areas) as they navigate an inhospitable world and find that there is always some degree of hope that can be found, should someone have the ability to see past the suburban malaise that has discouraged far too many people from pursuing their ambitions, which is something that Anderson, as the eternal optimist that he has always been, seems to be readily invested in exploring throughout his films, being one of the key components that runs consistently through his career, which has seen him traverse a number of genres, while almost always keeping some element of humanity to his stories, regardless of the project.

Considering the inspiration behind it, one of the more distinct qualities about Licorice Pizza is that there isn’t actually much of a definitive story behind it – there are certainly primary characters existing within the orbit of one another over the span of a few months, but there is less of a narrative driving this story, and more of a particular atmosphere in which Anderson immerses us. The trials and tribulations of Gary and Alana are not shown through a thoroughly straightforward story, with the film instead focusing on exploring their friendship through a series of vignettes, set over an indeterminate amount of time. This is essentially the director playfully experimenting with the narrative, using these two characters as vessels for something much deeper and more compelling, namely the fact that Licorice Pizza is a film about the San Fernando Valley at a particular moment in time, and the people that inhabit it, in that exact order. Anderson obviously adores this corner of the world, since it was the location of his upbringing (which was well-documented by the director himself during the production and promotion of the film), and while it’s not the first time he has made a film about this particular region, it is clearly the work of an older, more artistically-mature director fondly looking back at the past, rather than the rambunctious young wunderkind that made Boogie Nights and Magnolia, which looked at the same general places, but from a far more cynical perspective, one that was more focused on subverting expectations than it was offering wholesome entertainment, which is essentially the main intention of Licorice Pizza, which is a much more charming and gentle film, but one that still has Anderson’s distinct appreciation for a particular kind of storytelling. Any filmmaker that creates something set in a place to which they have an intimate connection is naturally going to be defensive of their work, but Anderson invites us into this world, encouraging us to accompany these characters on their journey of self-discovery, and the film is ultimately much better for taking this approach, since it leads to a much warmer experience than we’ve probably ever gotten from a director more known for his slightly more sardonic viewpoint.

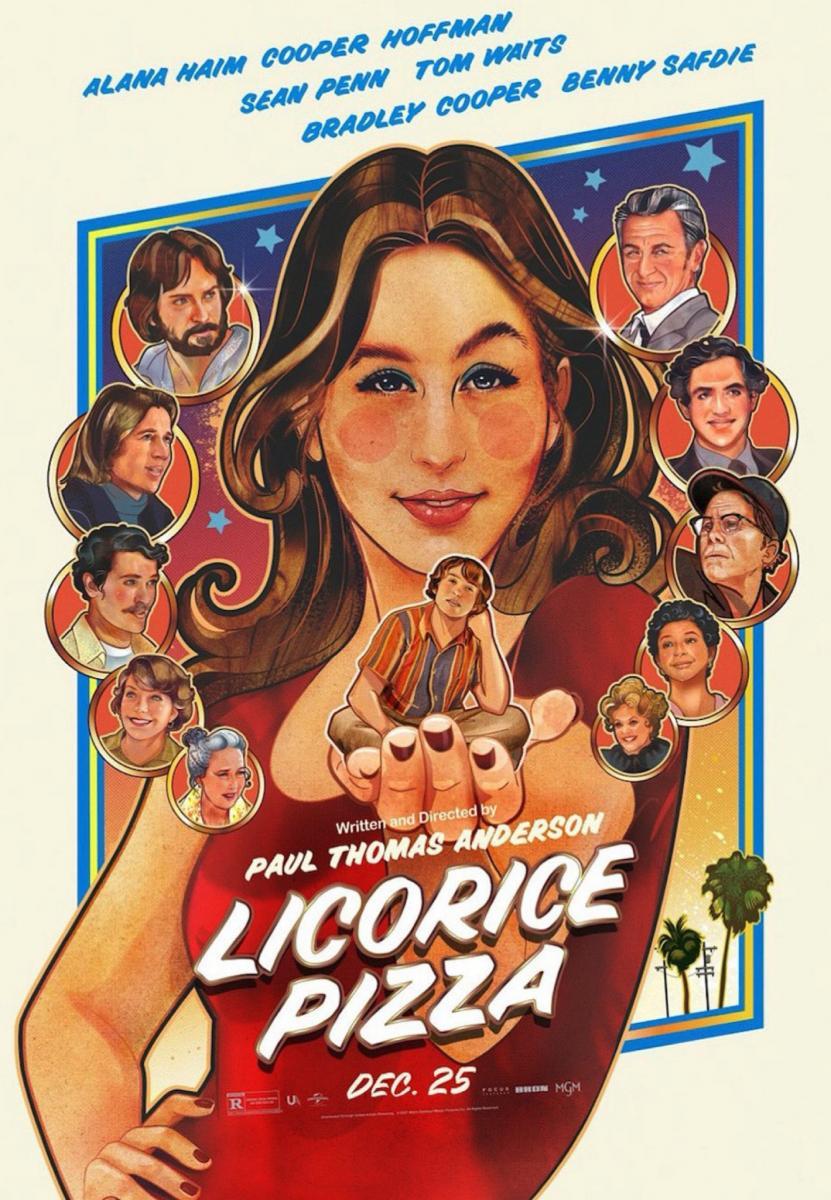

However, as much as Anderson may be very fond of the San Fernando Valley and would very likely be able to set far many more films in his hometown, they’d mean nothing without carefully-constructed characters that exist to service his vision. He is notoriously an excellent director when it comes to actors, having brought out career-best work from several actors over the course of his filmmaking journey. Many have pointed to how he redefined the careers of many actors, and he is indeed a brilliant filmmaker when it comes to giving great roles to actors we may not expect – but something Anderson does even more effectively is nurtures the careers of newcomers, having provided a platform for a few notable actors to get their start, or at least turn in a breakthrough performance. Licorice Pizza is one of the best examples of this, since at its heart, there are two characters played by a pair of actors who had never worked professionally before, but somehow managed to not only turn in brilliant performances, but occupy the central roles. His close personal connection with her band impelled Anderson to take a risk in casting Alana Haim, while his beautiful friendship with the late Philip Seymour Hoffman resulted in his son, Cooper Hoffman, being given the other leading role. It goes without saying that both Haim and Hoffman are absolute revelations in Licorice Pizza – for first-time actors, they’re incredibly natural and comfortable on screen (undeniably the result of both of them being involved in the entertainment industry for years – the former by way of her critically-acclaimed band, the latter growing up the son of one of the most revered actors of stage and screen). These are performances that define the idea of a breakthrough, and they’re both so incredible, scene-stealing work from the likes of Bradley Cooper and Sean Penn seem eclipsed by the sheer weight of what Haim and Hoffman were doing throughout the film. It only helps that Anderson truly loves these characters, enough to develop them far beyond just mere archetypes, shading them in far more than someone without genuine compassion for their creations may have been able to, which adds to the general charm that makes Licorice Pizza such a wonderful film.

Anderson’s perspective is one that is clearly self-reflective in a very tender way, but nostalgia has not softened it to the point where he has lost his subversive edge. In fact, quite the contrary is true – while it may be a more gentle film, Licorice Pizza is far from a lacklustre production in comparison to his previous work. Some may even argue that this is amongst some of the director’s most experimental work, since he is playfully challenging the narrative process, disregarding traditional storytelling structure and instead going in search of a more natural way to unravel the narrative. The film has a very authentic feeling surrounding it, which is a result of Anderson’s steadfast refusal to follow conventions throughout, instead choosing to dismiss patterns that are tried and tested in exchange for an approach that emphasizes the smaller details. Unlike most coming-of-age films, which seem to take the form of major moments in the lives of the protagonist, strung together to form an album of formative events, Licorice Pizza pays attention to the gaps between these moments, finding beauty in the mundane situations, and repurposing banality into something absolutely gorgeous. The structure may be simple, but it is far from pedestrian – each detail is well-placed, and eventually forms a vivid mosaic of these two characters, both in their individual lives, and their experiences together. The intersections between their varying backgrounds (in terms of culture, age and experience) create a stunning tapestry of two people who love each other – I am hesitant to call Licorice Pizza a romance, not only since this aspect has courted some controversy, but also due to the fact that this is less a film about romance in the traditional sense, and more a series of moments that demonstrate two people growing to adore and appreciate each other through embracing their own flaws, and starting to love themselves. This is what makes Licorice Pizza so special, since anyone can tell a love story, but very few can do so in a way that represents the deeper kind of love that exists between two lost souls finding each other at an opportune moment, and taking advantage of that spark, which eventually leads to a lifelong companionship, the details of which are unnecessary, since the intention behind this approach are far more interesting.

Whether one sees it as a sign of reliability or predictability, Licorice Pizza delivers exactly what we’d expect from such a story – it’s a heartwarming coming-of-age film set in the sunny suburbs of working-class California in the 1970s, made by someone with a distinct visual style (even more so considering Anderson worked as one of the cinematographers on the film) and the wide depth of knowledge, which is reflected in everything from the minuscule cultural references, to the beautifully curated soundtrack that immerses us in this era, rather than just being taken straight from a compilation of the decade’s greatest hits. Anderson is a very gifted filmmaker – he may be slightly overpraised in terms of being called one of the greatest filmmakers of his generation, (despite likely not even showing an iota of what he is capable of doing), but one can only acquire such a title when they have been producing a steady stream of high-calibre work, of which this film is undeniably an addition. There’s a kind of gentle sensitivity that sharply contrasts with the more satirical elements, which ultimately lead to a film that is extremely riveting, but in a way that is quite insightful and personal, rather than aiming to be a universally resonant piece of storytelling. Anderson truly made something special with Licorice Pizza, a film that is built on a foundation of authenticity, choosing to take a firm stance against artifice, instead handcrafting a genuinely touching story that has many interweaving facets. Touching on issues such as the process of transitioning from adolescence to adulthood, the burden of peaking too early, and the feeling of falling in love, the film has many fascinating ideas, and while they may not be delivered in a way that is entirely perfect, the flaws are acknowledged and embraced, reflecting the imperfections of the main characters, who only add to the naturalism of this heartwarming film that proves how the most effective stories are often those that are most simple, since nothing resonates more than a stark and meaningful reflection of life as it is, which is precisely what Anderson strived to achieve with this film, and accomplished with unbelievable accuracy, and an abundance of genuine heart.