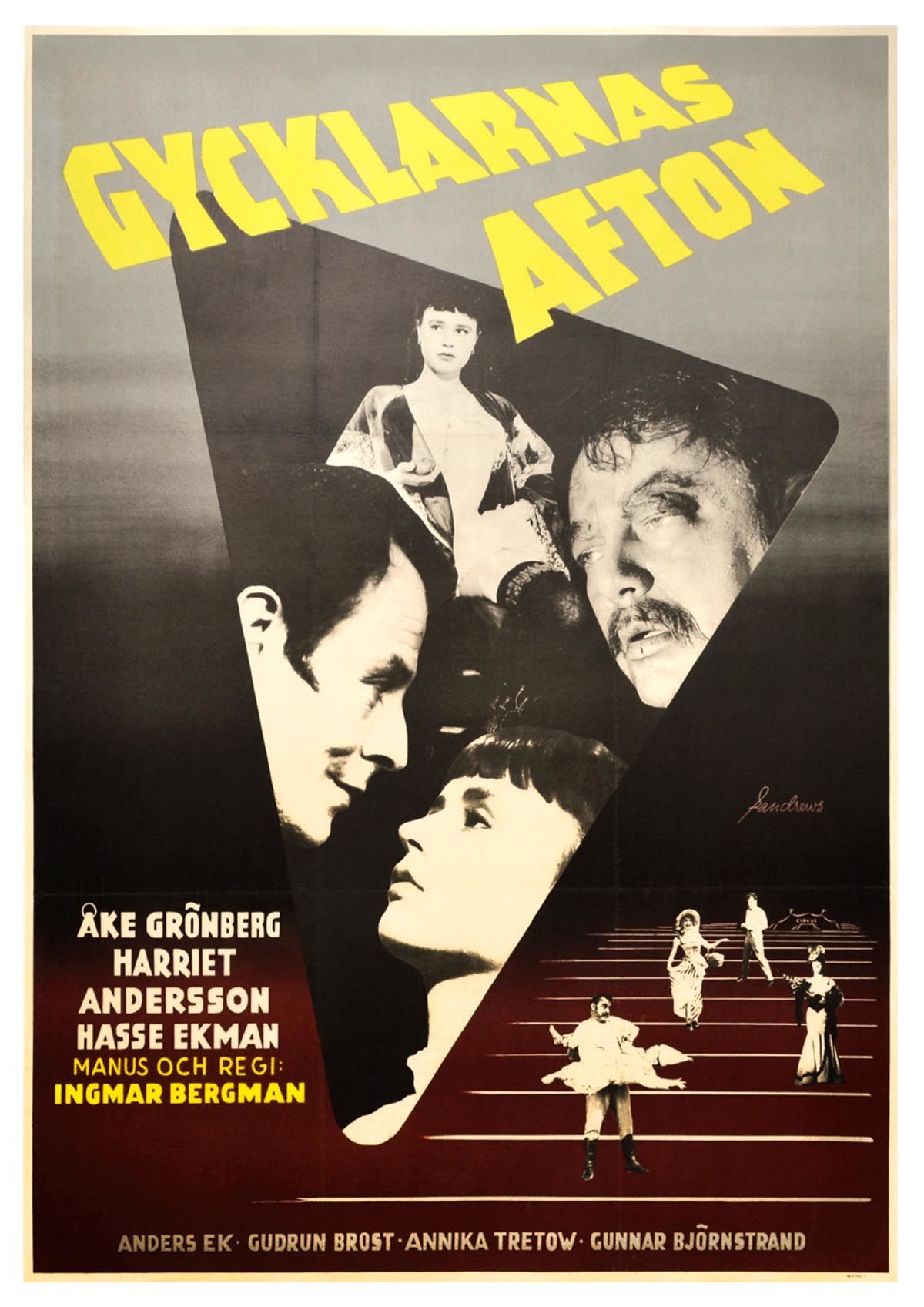

Depending on how you look at it, life is a comedy masquerading as a tragedy, or vice versa. This is the foundation for Sawdust and Tinsel (Swedish: Gycklarnas afton), the ambitious character-driven drama that serves as an early entry into the long and prolific career of the iconic Ingmar Bergman, who may have still been on his way to defining himself as arguably one of Europe’s most celebrated auteurs, but was already quite an original voice, even in his slightly younger years. The story of a carnival making its way through working-class Sweden and encountering various challenges with the local population, while still dealing with their own personal quandaries, is fertile ground for a deep and insightful analysis of the human condition, something that Bergman had a great deal of experience exploring throughout his career. He wasn’t a novice, having just under a decade of experience in the industry, but he wasn’t yet the acclaimed artist he would grow to be – and in many ways, Sawdust and Tinsel could be considered his first masterpiece, the film that brought together all the components that are most widely-celebrated about Bergman’s work – a distinct visual palette, a strong script that pays attention to its characters as much as it does the socio-cultural milieu, and a sense of enchanting, provocative candour that allows him to venture deep into the lives of these individuals, extracting earnest and complex commentary about their existences, and how it relates to the broader ambitions of the film. In short, Sawdust and Tinsel is a small but substantial effort from a director who would frequently peddle this kind of deep and insightful drama, being a resounding success, even for something that came relatively early in his career.

From the first moments, Sawdust and Tinsel doesn’t quite feel like anything we’re likely to see all the often when it comes to cinema – Bergman was a versatile filmmaker, but a quality possessed by many of his films (especially those focused on Swedish society) was a sense of detachment from reality. There is an argument to be made that the director’s most common modus operandi for telling stories was through the lens of offbeat fairytales, which certainly is very common here. The idea of a travelling circus troupe traversing the countryside is already enough to create a sense of fantasy, and Bergman seems to embrace this side of the subject, while still not deviating from his more serious intentions. Finding the balance between the very serious, gritty tone and the sweet and magical setting may not have been easy, but Bergman seems to have easily achieved it without too much effort, drawing on his own curiosities as a filmmaker and storyteller to situate us in this world, where we are so engrossed in the imagery and atmosphere, we don’t even notice how bleak the story gradually becomes. Bergman was not only a master of visual style and strong stories, but someone who could establish a very clear and direct tone for his films, luxuriating in whatever particular approach he deemed was most necessary to tell this story, and gradually pulling its various layers apart, revealing the complexities that lie beneath them, a quality that even his most straightforward films seem to follow. It doesn’t adhere to a particular pattern, since we can rarely tell where the film is taking us, but through his rich and evocative approach to the filmmaking process, and his ability to find depth in the most unexpected of scenarios, Bergman truly achieved something special with this film.

Bewildering, but in a way that feels very constructive and meaningful, rather than just being for the sake of realizing particular artistic quandaries, Sawdust and Tinsel represents a radical step forward for the director, who seems oddly enamoured with the idea of deconstructing something as cherished as the circus, repurposing it as the setting for a haunting social drama. There isn’t much comedy in this film, at least not in terms of what we explicitly see, which seems like a deliberate choice – one of the central characters is a clown, who is revealed to be one of the most tragic characters in the film, a victim of deep insecurity and mockery for factors outside of his control. The contrast between the setting, and the interweaving stories that come about as a result, is powerful, and lends this film a lot of credence as a social drama. Bergman had a penchant for telling these very intimate, character-based stories, and through working with some very impressive actors, some of which are unfortunately not as well-known today as they were at the time of this film’s release (but still represent some of the best performers Sweden had to offer), it’s unsurprising that his work reflected a keen sense of humanity, especially in how each one of these characters feel absolutely genuine, as if they were plucked directly from reality, and filtered through the perspective of a director whose entire career was driven by his majestic approach to looking at ordinary people in particularly challenging situations, and how they work their way out of such crises, some of them resorting to desperate measures, others being more calculated in their attempts to find a path away from their difficulties, whether physical or mental. It’s a fascinating approach to storytelling, and it may have been better realized later on in his career, but Sawdust and Tinsel has a strong sense of humanity embedded deep within the story.

However, as much as we can layer on praise for the approach to telling the story of these circus performances, Sawdust and Tinsel is just as impressive from a visual standpoint. Bergman wasn’t only able to weave together impactful and humane stories, but also craft them with such intricacy, his technique as a craftsman rivalling that as a narrative storyteller. Mercifully, there was an abundance of imagery that the director and his regular cinematographer Sven Nykvist could use as inspiration for this film – the circus has always been built on a few indelible images, all of which are used in some capacity here in the construction of this stunning film. It’s a beautifully-made film, but it’s never excessive – each choice is deliberate and leaves an impression, existing for the purpose of furthering the story, rather than just being a spectacle for the sake of captivating viewers. The bare-boned production design, combined with a few eccentric choices in terms of costume and location, make for a layered film that is as committed to creating something that looks beautiful as it is getting into the mind of these characters. Several scenes find the two aspects of the film working in tandem, creating a sense of symbiosis between the two that is absolutely unforgettable, especially when we realize how Bergman was always able to find the balance between the two. Even when making something as relatively simple and straightforward as Sawdust and Tinsel, which uses its carnivalesque imagery very sparingly (reserving it for only key moments), there is something of value to find, whether it be a particular shot, some of which being amongst the best Nykvist ever composed, or an entire scene, where the aching beauty of the filmmaking contrasts the poignant emotions reflected on screen.

It doesn’t stand up much against some of his other projects that would come later, and in many ways it seems like Bergman is still working to establish his voice – but Sawdust and Tinsel is still a remarkable film, an intimate and daring drama that cherishes its characters, respects the cultural institution and provokes thought with its insightful, earnest exploration of love and betrayal, all done through the lens of an abstract glimpse into the lives of a circus troupe trying to make their way through the hostile world that seems to see them as outsiders, rather than human beings with the same emotions, desires and curiosities as those in more traditional industries. Everything that made Bergman such an interesting filmmaker can be found here – the gentle humour, the sweeping moments of romantic melodrama, the intricate control of character and the genuinely insightful analyses of the human condition, all of which converge into this wonderfully complex portrait of a group of individuals divided by their different perspectives, but brought together by their feelings of alienation. Beautifully-made and incredibly powerful in both character motivation and emotional content, Sawdust and Tinsel is an incredible film, and a very important piece of filmmaking in terms of seeing the earlier origins of the elements that would serve as the foundation for the playful ponderings and curious artistic expression that would eventually become one of the greatest careers in the history of cinema.