There are three works I consider to be the greatest in the history of English literature – The Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon, Beloved by Toni Morrison, and “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight”, epic chivalric odyssey written by an anonymous poet, being one of the earliest surviving works of known literature. The latter is the subject of one of the year’s best films, with David Lowery (who is amongst the greatest American directors working in the medium today) writing and directing this fascinating medieval text. The Green Knight is not the kind of film we’d expect it to be – it certainly has all the components of a strong historical film, but with every familiar element, there are half a dozen surprises patiently waiting to shock the viewer, but in a way that is constructive and consistently meaningful. Lowery, who has made something of a career out of using his distinct authorial voice to tackle some very interesting subjects, was the perfect person to helm The Green Knight, if only for the sake of it being a film that plays into his sensibilities as an artist – whether in his approach to the quest narrative, or the visual scope of the film, he is constantly pushing forward and trying something new, relying less on the films that came before (which still serve as loose inspirations, rather than guidelines), and more on the spirit of the text, which has not been done appropriate service until now, when this extraordinarily gifted filmmaker and his posse of equally creative collaborators united to take this fascinating poem and form it into an even more magnificent film that does not only pay tribute to the original text, but also to the entire genre of literature from which essentially all art descended.

While we do regularly see films set in the medieval era being produced, it’s been a while since we’ve had a film that is somehow both enthralling and artistically resonant. The Green Knight plays to both sides of the audience’s expectations for this kind of film – on one hand, it is a lavish, extraordinarily beautiful historical epic, the kind that many filmmakers aspire to make. On the other, it’s a complex, cerebral film that touches on themes relating to individuality, nature and transcendental existentialism – the comparisons between Lowery and Terrence Malick may seem tenuous, but there are certainly similarities in how they approach such discussions, particularly in their emphasis on allowing the work to speak for itself. Yet, The Green Knight, much like the titular character,is a different beast entirely, an ambitious and daring project cobbled together from fragments of the antiquity, and filtered through the perspective of a truly gifted filmmaker, whose career may have only yielded a small handful of films, but where each one of them carries a resonance that could rival that of any of the directors that inspired Lowery. With this film, he quietly ascends to the status of one of contemporary cinema’s most awe-inspiring artistic voices, where the perfect marriage of style and substance doesn’t only produce a great film, but rather provokes something very close to a religious experience, the purely ethereal nature of the filmmaking being absolutely staggering. It’s almost indescribable the spectacle contained within this film – any work of art that can actually make the viewer question if they are seeing something in reality, or if they somehow fell into a waking fantasy, is going to carry an abundance of merit, and few films have been more effective in constructively challenging conventions more than The Green Knight, which is very close to a lucid dream captured on film.

Part of what makes The Green Knight such a resounding success is that it is singularly uncategorizable – while it’s tempting to label it as a medieval epic, since that is what it is at its most fundamental form, there are a range of different genres that inspired it. Like most classic epics, this film makes use of a wide range of ideas and conventions, drawing our attention to various themes at different moments. There are forays into romance (both in the literary sense, and in the actual demonstration of lust and passion), psychological horror and ecological fantasy, with several scenes combining several of these to form a very distinct narrative landscape. Undeniably, Lowery is taking a few liberties with this story – the original text was comparably short, and didn’t feature several of the details we see throughout the film. Yet, these are all necessary changes, since the story itself is kept relatively intact, but Lowery expands on the world in a way that is always very constructive, adding new aspects to this epic tale that make it even more enthralling. The further he pushes this narrative, the more intense his efforts go in realizing this peculiar version of the world. The film exists at the perfect intersection between historical drama and fantasy epic, and borrows liberally from both, containing the intricate, cultural commentary of the former, and the awe-inspiring surrealism of the latter – and Lowery’s decision to tell this story around the fantastical elements (rather than fully succumbing to them) is part of the brilliance, since it never feels as if he is venturing too far out of the realm of plausibility, placing the audience in the position of the main character, where we begin to question whether what we are seeing is real, or just mere delusion caused by the length of his journey – one of several fascinating provocations that make The Green Knight such an enduring film.

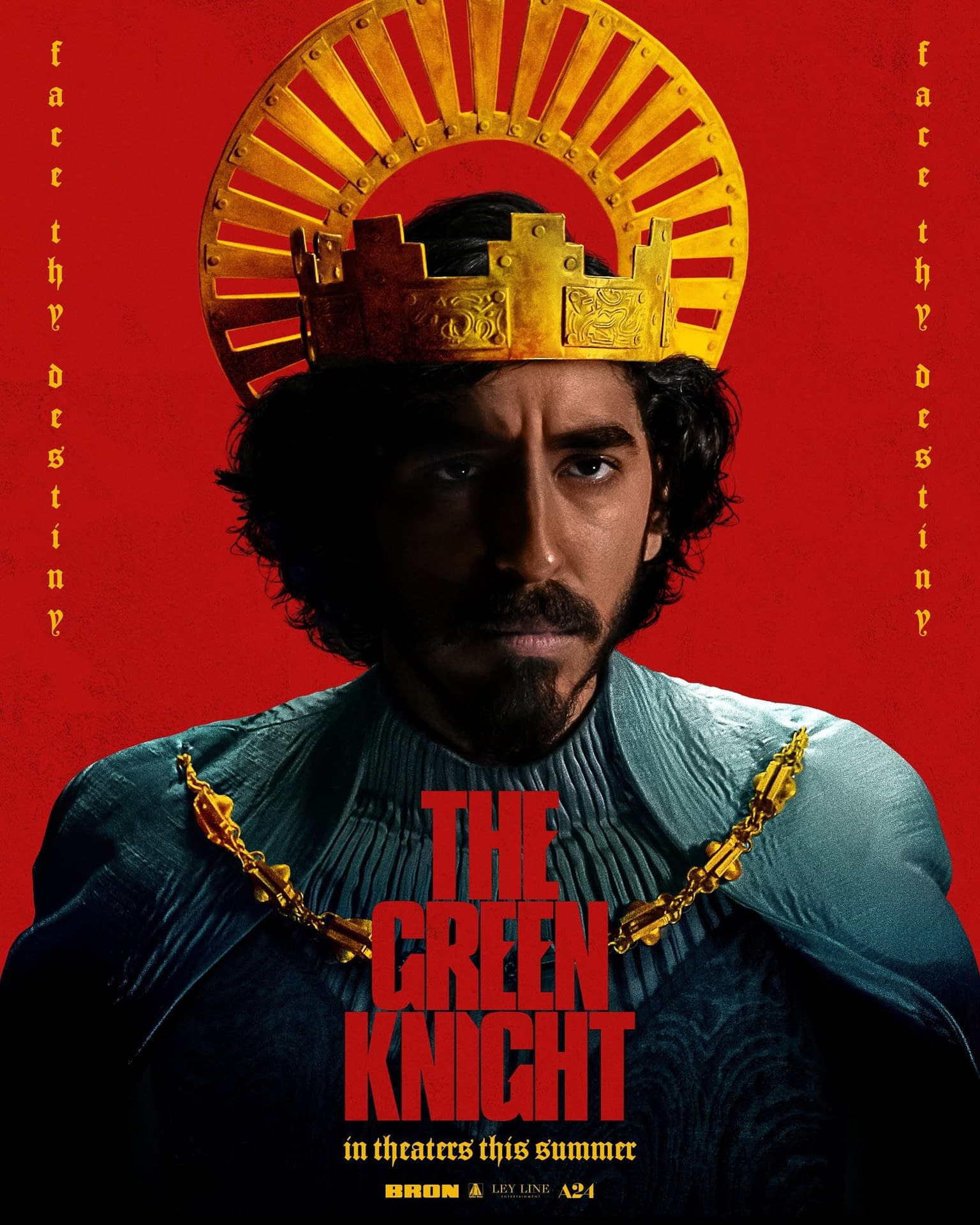

At the heart of this film is an ensemble composed of actors from several different parts of the world, all of whom commit entirely to following Lowery on this journey into the past. Dev Patel is an incredible actor, and he is turning in one of his finest performances in the part of Sir Gawain, the tragic hero who finds himself having to pay the price for his arrogance by undergoing a journey that is very likely going to end in his demise, the subject of which continues to haunt him, almost as if his uncertain fate lingers as a prophetic spectre, showing him that this odyssey is not one that is going to yield particularly positive results. Considering how internal this film is, and how it focuses as much on his mental travail as it does his physical journey, Patel’s performance is simply extraordinary, filled with complexity – considering the excellent work he has done over the past decade, this is hardly a surprise, and it’s always a welcome reminder that he is by far one of the most exciting young actors working today. Accompanying him on this journey at different parts are the likes of Alicia Vikander (in dual roles), Joel Edgerton, Barry Keoghan and Ralph Ineson, the latter managing to accomplish the near-impossible by playing a character that is almost entirely composed by computer-generated imagery, but still managing to emote in ways that are both terrifying and oddly touching. Even smaller roles from Sarita Choudhury and Sean Harris, as the people who initially placed Sir Gawain in this position, leave a considerable impression. It’s not often that we find a film that is both a visual spectacle and a showcase for its actors, but as someone who has always been a proponent of both through his approaching to the artistic process, it was foolish to expect anything less from Lowery, who once again casts his film exceptionally well, and manages to extract some incredible work from these gifted collaborators.

The quest narrative is one that has been told for centuries throughout literature, with the idea of a valiant individual undergoing a journey to accomplish something being fertile ground for a lot of insightful commentary. These stories tend to carry an incredible amount of complexity, which is delivered in simple narratives that contain social messages, parables that were intended to educate observers to these talents. The Green Knight doesn’t approach it from exactly the same perspective, with the ambigious ending (whereby we are left entirely uncertain about whether Sir Gawain met his demise at the blade of the titular being, or if he managed to escape through his demonstration of bravery and valour) implying that there isn’t necessarily a lesson to be learned here, but rather a series of moments in the life of this character as he ventures into the unknown. The experience of watching The Green Knight is less about making sense of this world in which it takes place (which is undeniably gorgeous, but deeply aloof), and more capturing the bewildering mystique of the past. Whether it be giants lumbering through the open plains, which is possibly the most awe-inspiring scene of the year, or sentient animals that accompany the main character on his journey, there is something off-kilter about this world, and working alongside director of photography Andrew Droz Palermo, Lowery constructs a deeply affecting depiction of what the medieval world looked like in the imagination of these pioneering storytellers. Each frame of The Green Knight is a painting in motion, a perfectly-constructed collision of visual splendour and narrative depth, which immediately situates this as one of the most beautiful films of the past decade, and one that is doubtlessly going to inspire future filmmakers in much the same way that Lowery was influenced by those who came before him.

We can never accuse Lowery of lacking ambition – every one of his films have been the epitome of audacity, whether it be the bare-boned melancholy of A Ghost Story, or the old-fashioned thrills of The Old Man and the Gun, or his attempts to revolutionize Disney with Pete’s Dragons – yet, it’s The Green Knight that perhaps finally consolidates him as a supremely gifted director. He is no longer a talented young director with potential, but rather a full-formed artist that has made only half a dozen films over the past decade, but where each one has been an unimpeachable masterpiece in its own way. His most ambitious production in terms of both scope and story, The Green Knight is a major achievement. Demonstrating both his ferocious control of the narrative, and his seemingly endless imagination that has allowed him to engage in a series of fascinating cinematic experiments over his career, Lowery’s work in The Green Knight is utterly impressive, feeling like the genuine artistic endeavour of someone thoroughly invested in pulling apart the layers of both the visual and narrative landscapes evoked in this ancient text, using his perspective as a launching point for a daring, evocative film that somehow manages to blend historical drama with psychological thriller, being both provocative and stunningly beautiful. The Green Knight is absolutely stellar, and by far one of the year’s greatest works – and whether it be for the unique interpretation of this incredible text, which is of interest in terms of both the history of literature and language in general, or the gorgeous process of bringing this story to life, Lowery achieved something absolutely phenomenal with The Green Knight, a film that tends to linger in one’s mind long after we have retreated from this world, leaving an indelible impression that will likely continuously bring us back into this peculiar, abstract version of the past.

Good review….I personally loved this movie. Yes, the film is quite artistic and has that oh so “arthouse: feeling that actually works. However, there are plenty of WTF moments. Still, for better or worse, I think that The Green Knight is a solid and fantastic film to watch.