There were many great filmmakers that defined the screwball film, which dominated the comedy genre in the 1930s and 1940s, but two in particular redefined what these films meant. The first is Ernst Lubitsch, arguably the finest comedic director to ever work in the medium, and the other is Preston Sturges, whose work reflects a more keen maturity than those made by his contemporaries. Both directors’ names evoke the idea of quality and nuance, which made them amongst the finest to ever work during the Golden Age of Hollywood, where many artists honed their craft and established themselves as vitally important creative minds during the formative era of arguably the most dominant form of media. Sturges is of particular interest for us at the present moment, since we’re discussing Sullivan’s Travels, which is often considered his masterwork. The first two years of the 1940s were a notoriously prolific time for the director, as he put together a staggering four motion pictures, some of them being more unheralded (The Great McGinty and Christmas in July), while others are canonical classics, such as The Lady Eve and the film we’re talking about today. Sullivan’s Travels has proudly taken its mantle as arguably the most affecting comedy of the 1940s, a film that contains numerous themes that were cutting-edge for the time in which this story was told, and remains as resonant today as it did eight-decade ago when Sturges undertook this enormous challenge to bring life to the characters he created based on his experiences as a playwright and industry veteran, in what is quite possibly the first truly historical Hollywood satire to be produced at a time when the industry was still finding its footing.

Sullivan’s Travels is a film that has found its place in the upper-echelons of the world of comedy, functioning as the rare comedy that elicits as many laughs as it does tears, with the oscillation between the two being the foundation for the enormous success of the film. Any discussion of Sturges will likely bring up the fact that he was one of the most interesting auteurs at a time when there was an enormous divide between screenwriters who feverishly wrote films for major studios, and the directors hired to shepherd these productions forward, bringing them to life under the careful guidance of the omnipotent studio executives that were nearly always the final authoritative word on a film’s production. Sturges nearly always directed from his own screenplay, and while there have been countless great filmmakers that have worked well with writers, it’s easy to see how Sturges’ work is borne from his own creation, each line of dialogue being captured exactly as it was intended when pen was put to paper in the conception of this film. Without the constraints of having to adhere to words written by another artist, and seemingly given free-reign by the studio executes (possibly a result of the director also acting as an uncredited producer on the picture), Sturges was able to playfully deconstruct the industry in his own unique way, subverting the idealistic image of Hollywood that not many at the time knew about outside of sordid rumours that were often more fact than fiction, while still keeping an iota of reverence for the people he was satirizing, proving that Sullivan’s Travels, even at its most scathing, is as respectful as it is outright hilarious, which is truly an achievement for a film as deeply funny as this one.

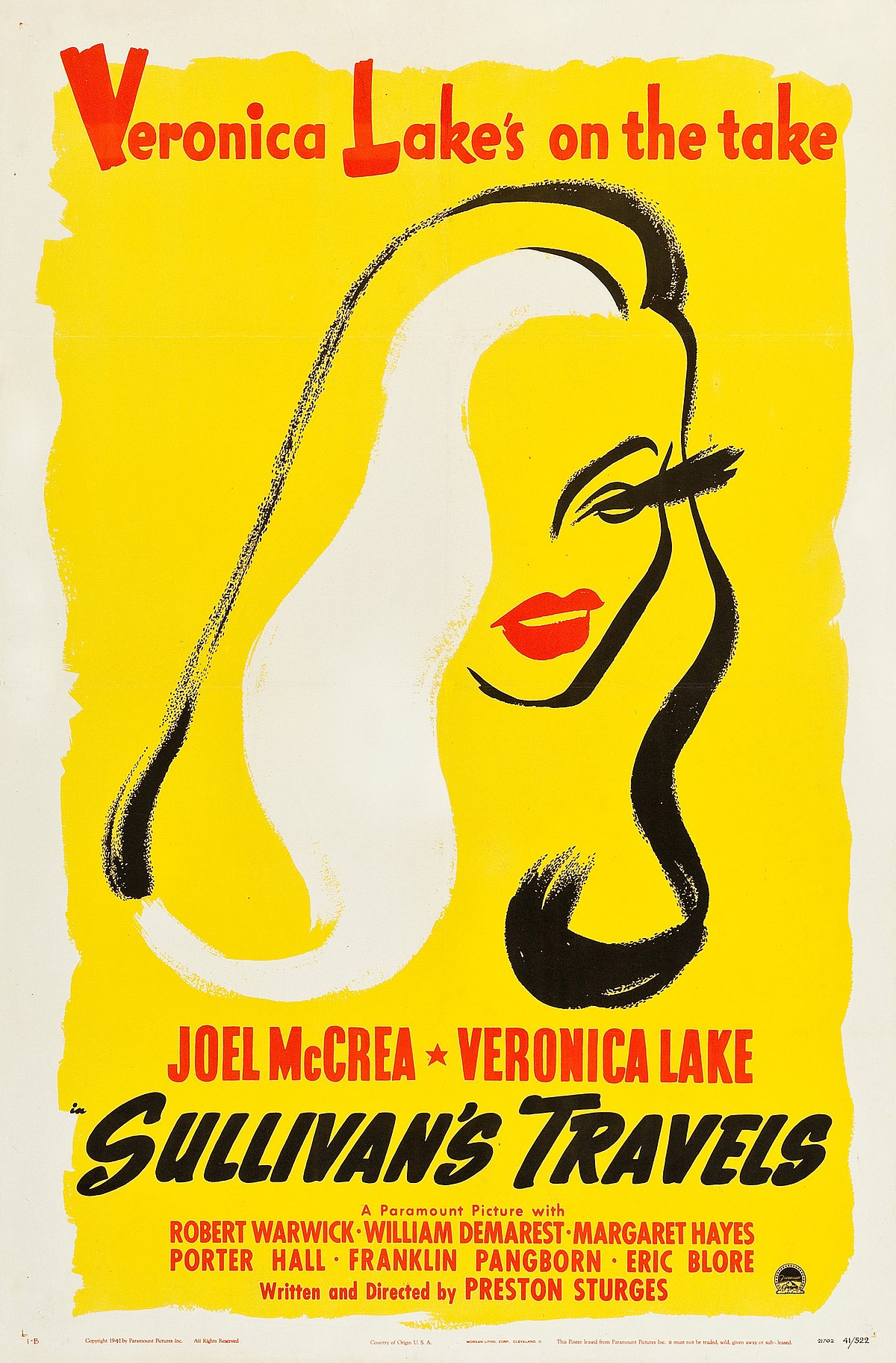

Tonally, Sullivan’s Travels is not what viewers may expect. There had been a number of comedies made about Hollywood in years prior to this, many of them extremely funny and entertaining, as mainstream cinema has never been against playfully mocking itself, as long as it is within reason. At the outset, this film seems to be following a similar pattern, and the premise – which follows a frustrated film director who decides he needs to first experience hardship before daring to make a film about it – doesn’t do much to assuage the feeling that Sturges made an upbeat and hilarious comedy that sees our titular character undergoing a series of quirky misadventures, accompanied by a dashing young vagabond who considers herself something of a femme fatale, despite being as mysterious as the director’s intentions in undergoing this metaphysical expedition to experience life on the other side. However, Sullivan’s Travels is a film that is constantly evolving before our eyes – it moves from a quaint showbusiness satire, to a darkly comical romance (with elements of film noir embedded deep within its fabric), before culminating in a harrowing and heartbreaking final act, where the film finally reaches a particular point, both narratively and literally, where most of Sturges’ contemporaries would’ve been far too hesitant to venture, taking this charming comedy and turning it into one of the most challenging critiques of the social system ever put on film, with some of the imagery that occurs throughout this film being both spellbinding and deeply disturbing, in a way that lingers on in the viewer’s mind, much longer than any of the comedic moments that form the foundation for the story. Credit must be given to Joel McCrea and Veronica Lake, who aren’t only fantastic in the comedic parts of the film, but can easily switch over to more dramatic material when the film requires them to take these individuals to a more sobering location in terms of their characterization.

There’s an atmosphere of palpable tension that recurs throughout the film, with a certain complexity being present from the first moment. The likely reason behind this constantly shifting (but also quite consistent – it is far from unstable in terms of narrative) is that the director was taking a more experimental approach to the filmmaking process – he starts off at a recognizable point in terms of the story, with familiar characters and a plot that follows the same predictable beats that even the most revered screwball comedies tended to at the peak of the sub-genre’s popularity – and then he gradually strips away the very polished veneer, pulling apart the layers of the film and focusing on a range of issues that were extremely progressive for their time (which makes the fact that the film was the subject of a lot of divisive reviews, opinions differing massively on the nature of the storytelling and the successes and failures of Sturges’ filmmaking process), and still remain quite profound by modern standards. Naturally, this is all a result of the director pushing an agenda deeper than that of simply entertaining audiences, which is exactly what makes the final moments of the film so hauntingly beautiful. Something as simple as a scene taking place in a church, where the congregation consists of a blend of African-American churchgoers and white prisoners, separated by social and cultural divides, but united by their shared appreciation for a small but impactful cartoon. It makes the message of the film all the more potent, and elevates Sullivan’s Travels far beyond simply a mindless comedy, adding a staggering amount of gravitas to an already unexpectedly complex comedy – and it’s important to remember that, regardless of the serious message at the heart of the film, Sullivan’s Travels is still a very funny piece of filmmaking, it just carries a deeper meaning that is quite unexpected for a comedy produced during this era, where more serious stories were restricted to the appropriate genre, rather than encroaching on the supposedly sacred realm of comedy.

Sullivan’s Travels is a film that earned its reputation through earnest, engaging storytelling, telling a story that may have ruffled a few feathers and perhaps even caused some mild controversy, but in a way that is actually quite meaningful, since there is a progressive sensibility that underpins the film, informing the comedy and making it much more complex than a run-of-the-mill screwball, which are always endearing, but are often slightly more inconsequential than some more profound comedies that existed around the same time. Sturges was a remarkable writer and director, every moment of this film filled with his sparkling wit and visionary approach to conveying a deep message, some of it through the dialogue, others through wordless moments that depend on the visual stimulus to enrichen the story and add strength to the argument the director is making with this parable. Despite its very deep message, Sullivan’s Travels is never overwrought or too excessive in how it approaches its emotional content – every scene carries weight, even if it is only to set a foundation for the more subversive moments that populate the latter parts of the story. It avoids heavy-handed commentary or overt sensationalism, keeping everything quite light and endearing, until those final moments, where the true scope of Sturges’ intentions are made clear – and it speaks directly to our hearts and souls, keeping us entertained while prodding at our internal curiosity that is piqued by this film and its peculiar approach to representing deep social issues through the lens of an upbeat and charming comedy that proves how much merit there is in using humour as a powerful narrative tool, to the point where a small experiment resulted in one of the most important films to ever be produced during this particular moment in film history.