I have had a difficult relationship with Wes Anderson, which is something that I believe has been made very evident through my writing. No one would be more willing to put together a passionate response to the underrated genius that is The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, or rave about the brilliance of Bottle Rocket and its status as arguably one of the greatest debuts for an independent filmmaker of the 1990s. However, I’ve also criticized the direction his career has taken – I enjoyed Moonrise Kingdom and The Grand Budapest Hotel, but found them far too slight, and the less said about Isle of Dogs, the better. Perhaps it’s a case of being too overly critical, but there is something about his more recent output that seems disappointing, especially considering the promising start the director had when he first began unleashing his unique vision on audiences a quarter of a century ago. The French Dispatch is his most recent effort, and it required a couple of days of rumination and meditation to fully come to understand my reaction to the first. To not bury the lede, I did considerably enjoy this film, or rather considerable parts of it. It’s a film that works best as a series of components, some of them stronger than others, as one would expect from an anthology film. However, this is not a positive reaction that comes easily – for as many wonderful moments embedded in this film, there are those that are less-effective, hinting at the fact that Anderson is continuing to venture down a path that is heading towards being enveloped by his twee idiosyncracies, where he allows the stylistic cravings to direct the films, rather than the stories that would’ve normally guided his masterful films and made him such a formidable auteur in the first place. It makes for a film that is often just a bundle of quirks and eccentric details that sometimes strike gold, other times being close to insufferable – and the result is a jagged and vaguely disappointing anthology that strives for greatness, but perpetually falls short.

There really isn’t much that can be said about The French Dispatch that hasn’t been said about all of Anderson’s films over the past decade – they vary in quality (particularly the two that started the decade), but they’re all essentially the products of a director who is growing increasingly dependent on a few notable quirks, all of which are used in favour of his artistic curiosities. No one can fault Anderson for making films that reflect his twee inner psyche, which is drawn to such precise artifice. The problem comes when there isn’t much of a story to back it up, and where the narrative is about as paltry as the emotions, which are shoehorned into the film in a way that would seem like a betrayal to the director’s earlier works, which were driven primarily by the emotional content, and their ability to be enthralling and heartbreakingly beautiful, even when the visual scope was slightly off-kilter. Perhaps claiming that he as fully surrendered to the concept of style over substance is somewhat inappropriate, since there certainly are many merits behind The French Dispatch that prevent it from being entirely wasteful of its potential, but it would be equally foolish to suggest that this stands as one of the director’s best works, because it simply cannot compare. It may be difficult to improve on near-perfection, which is an apt descriptor for the better works Anderson produced earlier in his career, but even when he had the opportunity to do something slightly different, he aimed for the same kind of overly eccentric style of filmmaking, one where the emotional content isn’t believable, and where the story just feels like it is on the precipice of falling apart at the seams entirely, which is perhaps not what we’d expect from someone as celebrated as Anderson, whose name evokes the idea of quality for the most part, granted he did earn it based on his previous work – he is just struggling to maintain that reputation, and The French Dispatch isn’t much help to the case.

Logically, one would assume that the impetus behind The French Dispatch was that Anderson had a variety of ideas for films, but none of them possessed the depth to warrant being a feature-length film all on their own. Looking at them in isolation, it does make sense to separate them into individual segments, independent of the broader narrative – the story of a misunderstood artist incarcerated for life, a chronicle of student protests in post-war Paris, the kidnapping of the young son of a prominent public figure: these are all riveting and interesting stories on their own, and to have them placed against one another should logically result in something very exciting, especially under the shared theme of being a love-letter to journalism in the 20th century. On a purely conceptual level, The French Dispatch has a lot of promise, and I refuse to say that it squanders absolutely all of it. Anderson has made a good film – the problem is that it takes the form of one that was striving for a greatness I’m not entirely sure it was capable of achieving. In both instances, whether they are placed alongside one another, or are simply seen on their own, there’s a meagre quality to all these segments that could’ve used more work. It’s only made worse by the fact that they’re all of varying quality – the first segment is the strongest (so the film starts on its highest note, not always the best approach to an anthology), while the third is also quite good, leaving the brunt of the pressure on the middle segment, which not only has the unenviable task of following the best storyline, but also being the peak of the film, the longest and most substantial of the stories in theory, having the biggest platform, but the least to say. The inconsistency between segments is one of the more perilous challenges of the film, and is the primary reason that The French Dispatch starts to become quite repetitive, since they’re really treading similar narrative territory, just with different characters and altered intentions.

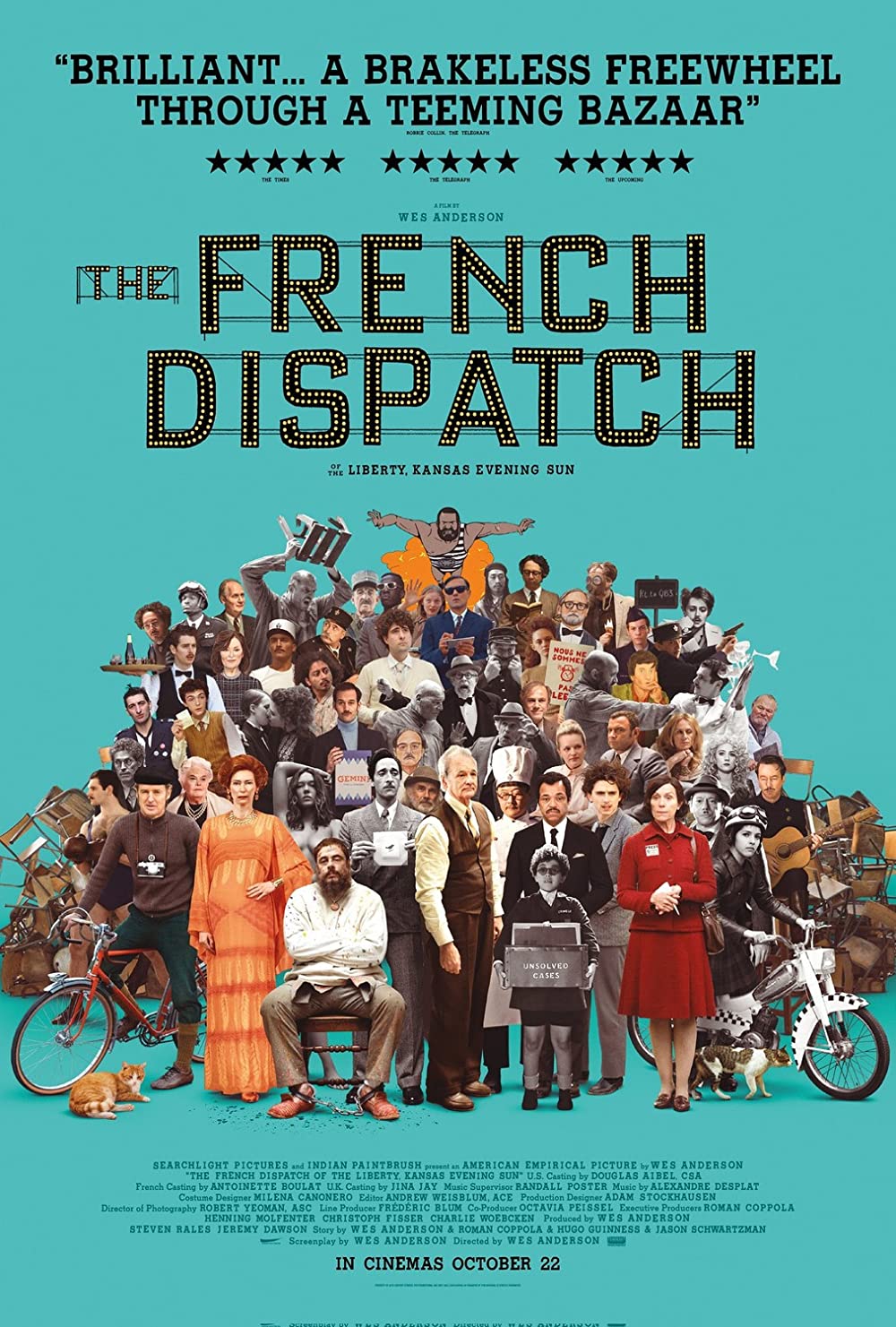

Undeniably, The French Dispatch has a strong cast, and is by far the most star-studded ensemble that Anderson has been able to put together to date. I’ve always admired not only the director’s ability to gather such a large repertory cast of regular collaborators, but to be persuasive enough to give them all interesting roles, even if some of them are not doing too much in the film in general. Nearly every one of the director’s most frequent actors appear in this film somewhere, whether playing a primary role (such as those by Tilda Swinton, Frances McDormand and Jeffrey Wright as the de facto leads of the film, by virtue of being the central characters in their respective segments), or a small cameo, playing a character that often doesn’t even much an official name, rather going by a description. A tremendous strength that this film has is that it uses most of its actors well – aside from the central characters, even those in the periphery are developed well. Had the film kept the same consistency in terms of the stories they occupy, or the worlds they populate, there is very little doubt that The French Dispatch would’ve improved considerably. When the director has as gifted a cast as he does here, and the good foresight to give each one of them a good character, it’s understandably a bit disappointing when it doesn’t really seem to be leading to anything in particular. As we’ve come to expect, there isn’t any particular standout – most of the actors are tremendous, and serve a solid function that adds invaluable contributions to the film. Personally, I found the best performance come on behalf of a newcomer to Anderson’s world, the incredible Jeffrey Wright, who embodies the spirit of a James Baldwin analogue with the same spirited passion and effortless dignity that he brings to all his roles – but the beauty of an Anderson film (even one that veers towards being disappointing like this one) is that each individual viewer will come out of it with a different standout, which is the sign of a great ensemble, and a writer-director who knew how to use them properly.

However, it is easy to relentlessly criticize, and Anderson is an easy target, since his overly twee style and preoccupation with symmetry and composition makes him the victim of a lot of needless disparagement, even when he is doing solid work. One of the positive aspects of The French Dispatch is that it is quite different, at least in terms of structure. Anderson takes a few short stories that could’ve stood entirely on their own, and weaved them together to form a film that uses these segments well. It is structured as if the viewer were reading a magazine, the pattern of the film being nearly identical to what we’d find when reading the kind of publication being portrayed here. Anderson also makes his cinematic inspirations quite clear – there’s an opening scene taken directly from Jacques Tati’s Mon Oncle (the director being a notable influence on Anderson, to the point where his frequent pastiches to Tati could be considered overwhelming to those without a penchant for the quirky physicality of these films and their unique methods of storytelling), and half a dozen other artists, whether fellow filmmakers that were pivotal in Anderson’s education as a director, or those in other fields, are proven to be influences on the film. This is where The French Dispatch is most successful – it wears its heart on its sleeve, and it isn’t afraid of making its inspirations known. Anderson often constructs his films from a variety of moving parts, and there is a delight in seeing the reverence he holds for the artists that preceded him. It makes the films frequent flights of fancy fruitful and fascinating, and considerably helps in developing it far beyond just an empty homage. Once again, the material is certainly there in The French Dispatch – the problem is that it doesn’t always seem like Anderson knows exactly what to do with it, and when faced with a difficult narrative choice, he’s unfortunately someone who defaults to the hackneyed technique of dazzling the viewer with visual splendour to distract from the story-based discrepancies. It’s a technique that used to work without a hitch, but which is slowly starting to be an unreliable narrative tool as audiences become more aware of the director’s very clear methods, causing us to yearn for something more meaningful to match the striking, gorgeous images that Anderson, director of photography Robert D. Yeoman, and the many creative individuals responsible for the look and sounds of this film, effortlessly provide for us.

Despite my reservations, I do think The French Dispatch is mostly very good, but falls slightly short of being brilliant as a result of Anderson succumbing to the temptation to fall onto the same reliable set of quirks that have cushioned most of his recent works, without doing too much to challenge himself. He knows that the style is distinct enough, and he clearly loves making these kinds of films, and we really can’t blame him, since he’s cornered a market that no one else was willing to work in, and now holds the monopoly on this brand of bijou, quaint period comedy that has single-handedly built his entire career. He is not on the wrong path with a film like The French Dispatch – it’s tempting to dive deep into a conversation about how Anderson is becoming a parody of himself – but rather, he seems to be moving at a glacial pace, focusing more on the spectacle, and not enough on the emotion. There isn’t a single moment in The French Dispatch where we feel those same distinctive tugs on the heartstrings as we did before. The musical cues are charming but not all that engrossing, and the character development is too weak for us to fully invest in their journey (although, it is difficult for us to form a relationship with a character in an anthology film), making every effort to fully surrender to Anderson’s style quite difficult, since there isn’t much to grasp onto. Structurally, he is trying something new in the form of a multi-chapter anthology film, and the intentions are both pure and admirable, so it’s tough to blame him when some of the aspects of the film don’t work, since there are some elements that are out of his control, and could only be proven to be successful or not through trial and error, which is certainly not something to which the director has ever been adverse. The flaws lie in the more traditional elements that are missing or too subdued – the emotional content, the abundance of heart and the genuine curiosity, which are all severely depleted, and replaced with an off-the-wall, eccentric bundle of quirks that may be enticing on the surface, but prove to make The French Dispatch a sadly much too inconsistent effort to really stand alongside Anderson’s best work, regardless of how strong some of the components of the film were, and how there was potential exuding from nearly every frame of the film, which yearned for a more refined and meaningful approach.